GitHub is not just a code hosting platform. It is your public engineering ledger. It shows how you think, how you structure problems, how you document tradeoffs, and how you ship. If you build software and it never lands on GitHub, as far as the wider technical world is concerned, it does not exist.

This guide walks you from nothing to a clean public repository that is properly licensed, tagged, and released. No clicking around aimlessly. No half configured repos. No “I’ll tidy it later.” We will automate the entire process.

1 Why GitHub Matters

Before the mechanics, understand the leverage. Recruiters, engineers, and contributors can see your work, which gives you visibility you cannot get any other way. Clean commits and structured repos demonstrate discipline, and that builds credibility in a way that talking about your work never will. Tags and releases formalise change through proper versioning, and GitHub Releases turn your repo into a distribution channel. Beyond all of that, issues and pull requests scale development beyond you by opening the door to community contribution.

If you are building WordPress plugins, internal tooling, or AI integrations, publishing them properly is a signal. Discipline in open source hygiene matters.

2 The Manual Way vs The Correct Way

The manual way looks like this: install Git, create a repo in the browser, clone it, copy your files across, add a README, add a LICENSE, commit, push, tag, upload a release, add topics, then go back and fix all the mistakes you made along the way. That is friction. Friction creates inconsistency. Inconsistency creates messy repos.

Instead, automate it once and reuse it.

3 One Shot GitHub Publish Script (macOS)

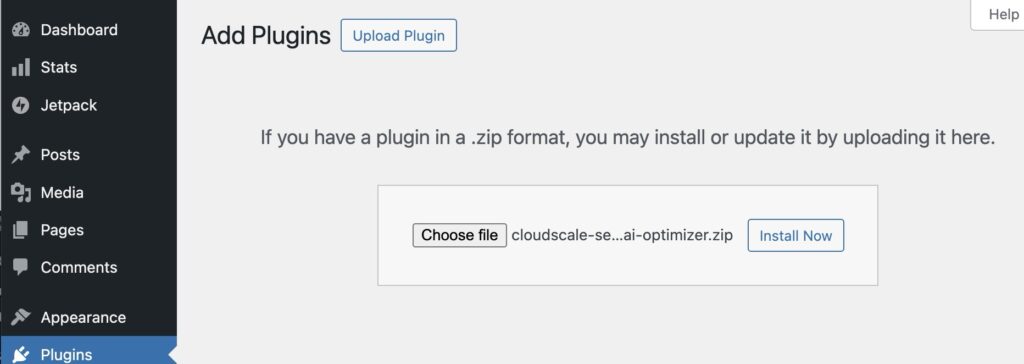

The script below handles everything in a single pass. It installs Homebrew if needed, then installs Git and GitHub CLI. It authenticates you with GitHub via browser OAuth so you never have to manually create tokens. It then scaffolds a clean project directory with a MIT license, a sensible .gitignore, and a README.md. From there it initialises Git, creates the public GitHub repo, pushes the initial commit, tags a release, and sets repository topics. You edit three variables at the top of the script and the rest takes care of itself.

Save this as github-publish.sh, then run it:

chmod +x github-publish.sh

./github-publish.sh

Here is the script:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# ============================================================================

# github-publish.sh

#

# One shot script to install tools, create a public GitHub repo, and publish

# your project as a clean, properly licensed open source repository.

#

# What it does:

# 1. Installs Homebrew, Git, and GitHub CLI (gh) if not already present

# 2. Authenticates with GitHub via browser OAuth

# 3. Scaffolds LICENSE, .gitignore, and README.md

# 4. Creates the public repo, pushes, tags a release, and sets topics

#

# Usage:

# chmod +x github-publish.sh

# ./github-publish.sh

#

# Prerequisites:

# macOS with admin rights.

# ============================================================================

set -euo pipefail

# ---------- configuration (edit these three lines) ----------

REPO_NAME="my-project"

REPO_DESC="A short description of what your project does."

VERSION="1.0.0"

# ------------------------------------------------------------

echo ""

echo "========================================="

echo " GitHub Open Source Publish"

echo " Project: $REPO_NAME"

echo "========================================="

echo ""

# ── 1. Homebrew ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

if ! command -v brew &>/dev/null; then

echo "[1/7] Installing Homebrew..."

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"

if [[ -f /opt/homebrew/bin/brew ]]; then

eval "$(/opt/homebrew/bin/brew shellenv)"

fi

else

echo "[1/7] Homebrew already installed."

fi

# ── 2. Git ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

if ! command -v git &>/dev/null; then

echo "[2/7] Installing Git..."

brew install git

else

echo "[2/7] Git already installed ($(git --version))."

fi

# ── 3. GitHub CLI ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

if ! command -v gh &>/dev/null; then

echo "[3/7] Installing GitHub CLI..."

brew install gh

else

echo "[3/7] GitHub CLI already installed ($(gh --version | head -1))."

fi

# ── 4. GitHub auth ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

if ! gh auth status &>/dev/null; then

echo "[4/7] Logging into GitHub..."

echo " A browser window will open. Approve the OAuth request."

gh auth login --web --git-protocol https

else

echo "[4/7] Already authenticated with GitHub."

fi

# ── 5. Scaffold project ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────

echo "[5/7] Scaffolding project directory..."

mkdir -p "$REPO_NAME"

cd "$REPO_NAME"

# MIT license (swap this for GPLv2 or Apache if you prefer)

GH_USER=$(gh api user --jq .login)

YEAR=$(date +%Y)

cat > LICENSE << EOF

MIT License

Copyright (c) $YEAR $GH_USER

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy

of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal

in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights

to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell

copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is

furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE

SOFTWARE.

EOF

# .gitignore

cat > .gitignore << 'GITIGNORE'

# macOS

.DS_Store

._*

# IDE

.idea/

.vscode/

*.swp

*.swo

# Build artifacts

node_modules/

vendor/

dist/

*.zip

*.tar.gz

# Environment

.env

.env.local

GITIGNORE

# README.md

cat > README.md << README

# $REPO_NAME

$REPO_DESC

## Getting Started

Clone the repository and you are ready to go:

\`\`\`bash

git clone https://github.com/$GH_USER/$REPO_NAME.git

cd $REPO_NAME

\`\`\`

## License

MIT License. See [LICENSE](LICENSE) for the full text.

## Author

$GH_USER

README

# Initialise git repo

git init -b main

git add -A

# Set commit identity from GitHub if not already configured globally

if ! git config user.email &>/dev/null; then

GH_EMAIL=$(gh api user --jq '.email // empty')

if [[ -z "$GH_EMAIL" ]]; then

GH_EMAIL="${GH_USER}@users.noreply.github.com"

fi

git config user.name "$GH_USER"

git config user.email "$GH_EMAIL"

fi

git commit -m "Initial commit: $REPO_NAME v${VERSION}"

# ── 6. Create repo and push ─────────────────────────────────────────────────

echo "[6/7] Creating public GitHub repo and pushing..."

gh repo create "$REPO_NAME" \

--public \

--description "$REPO_DESC" \

--source . \

--remote origin \

--push

# ── 7. Tag release and set topics ───────────────────────────────────────────

echo "[7/7] Creating release and setting topics..."

gh release create "v${VERSION}" \

--title "v${VERSION}" \

--notes "Initial open source release of $REPO_NAME."

# Add your own topics here. These help people discover your repo.

gh repo edit \

--add-topic open-source

REPO_URL=$(gh repo view --json url --jq .url)

echo ""

echo "========================================="

echo " Done!"

echo ""

echo " Repository: $REPO_URL"

echo " Release: $REPO_URL/releases/tag/v${VERSION}"

echo "========================================="

When the script completes, you have a public repository with a clean initial commit, a tagged release, and a structured open source project ready for contribution. The whole thing runs in under a minute on a machine that already has Homebrew installed.

4 Anatomy of a Good README

The README is the front door of your project. Most developers either skip it entirely or write something so vague it tells you nothing. A good README answers three questions immediately: what does this project do, how do I use it, and where is the license.

Here is a minimal example that covers the essentials:

# hello-world

A minimal CLI tool that prints a greeting. Built as a reference for clean

GitHub repository structure.

## Getting Started

Clone the repository:

git clone https://github.com/your-username/hello-world.git

cd hello-world

Run the script:

python hello.py

You should see:

Hello, world!

## Usage

Pass a name as an argument to personalise the greeting:

python hello.py Andrew

Hello, Andrew!

## Requirements

Python 3.8 or higher. No external dependencies.

## License

MIT License. See [LICENSE](LICENSE) for the full text.

## Author

[Your Name](https://your-site.com)

That is enough to tell someone everything they need to know in thirty seconds. You can always expand it later with sections for configuration, contributing guidelines, or architecture notes, but this baseline should exist from day one.

5 Final Thought

Most developers overthink GitHub and under invest in automation. The difference between a hobby repo and a professional one is not complexity. It is structure.

Automate structure once. Then focus on shipping. Your code deserves to exist in public properly.