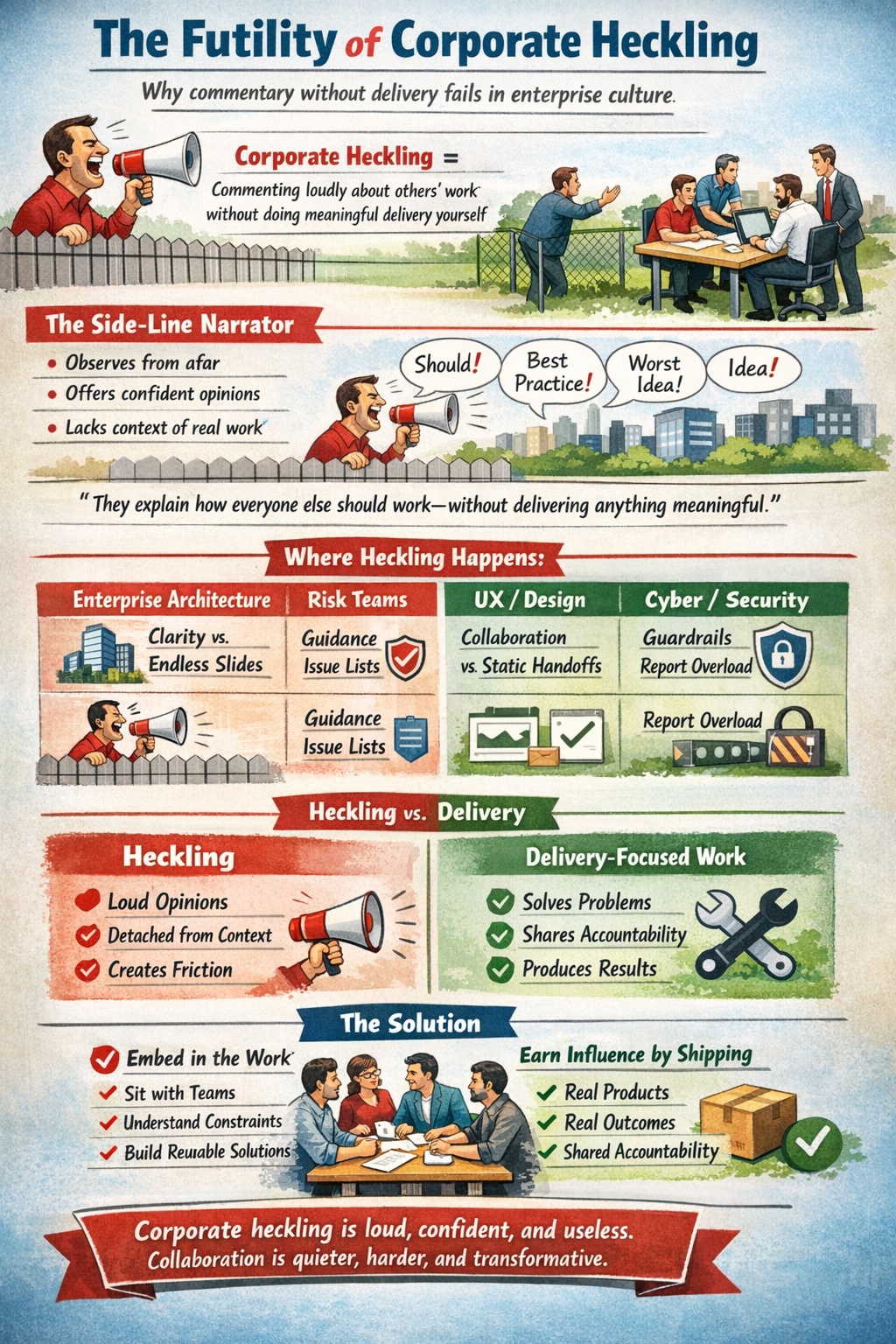

There is a peculiar sport played in large organisations. It looks like leadership and sounds like governance, hiding behind frameworks, maturity models, and operating rhythms. But in reality it is something far less noble. It is corporate heckling.

Corporate heckling is what happens when a function narrates from the sidelines with low context and high confidence. It is the art of describing how everyone else should work, without ever carrying the burden of delivering anything meaningful yourself. It is commentary at scale, divorced from the trade offs, constraints, technical debt, regulatory nuance, customer friction, and immovable deadlines that real teams wrestle with every single day, and it achieves nothing.

1. The Sideline Narrator

In every enterprise there are functions that slowly drift from enablement into commentary. They attend steering forums, publish decks, rate “maturity,” explain what good looks like, and diagnose other teams from a safe distance.

The pattern is predictable. They have all the answers. The delivery teams are immature. The architecture is fragmented. The engineers lack discipline. The product managers do not think strategically enough. What is rarely true is that these narrators have taken the time to sit inside those teams and understand why things look the way they do. They have not traced the historical decisions, absorbed the regulatory constraints, sat through production incidents at midnight, or tried to ship a feature under a hard date with incomplete information and an unpredictable dependency. Without context, ideas sound elegant. With context, they often collapse, because heckling is easy and delivery is not.

2. Enterprise Architecture and the Illusion of Superiority

Enterprise architecture is particularly susceptible to this disease.

At its best, architecture creates clarity of domain boundaries, coherent principles, and composable building blocks that make delivery faster and safer. It reduces cognitive load, prevents duplication, and enables teams to move independently without creating chaos. It is an accelerant.

At its worst, it becomes a commentary layer. A slideware practice that declares teams immature while producing nothing that reduces friction. A group that standardises vocabulary but never simplifies reality. A function that critiques design decisions without being present when those decisions were constrained into existence.

If architecture only appears to say no, redraw diagrams, and demand alignment to abstract models, it is heckling. If architects are not embedded in discovery, not present in solution design, and not accountable for operability and performance once the system is live, then they are spectators with strong opinions. Maturity is not declared in a deck. It is built in code, in platforms, in patterns that actually make delivery easier, and it is built by people who carry outcomes rather than narratives.

3. Risk That Never Risks Anything

Risk functions often drift into the same trap. It is easy to publish a list of findings, state what is non compliant, and point out gaps. It is much harder to sit in sprint reviews and guide decisions as they form, design controls that preserve velocity, or propose practical alternatives that balance safety with usability. Risk that lives in documents is narrative. Risk that lives in the room is influence.

If a risk function does not join the meetings where critical decisions are made, if it does not shape options before they solidify, it becomes another backlog item fighting for relevance. Another ticket to be negotiated, another control to be interpreted creatively under pressure. Real risk work produces insight that changes behaviour before the problem materialises. It does not simply annotate the aftermath and declare the team immature.

4. UX Without Skin in the Game

Design is not a handover ceremony. It is not a file labelled “approved” thrown over a wall to developers who are then expected to faithfully reproduce a static imagination inside a living system. If UX is not debating constraints with engineers during build, not tensioning performance against animation, accessibility against layout, or regulatory copy against clarity, then it is participating in theatre.

When the shipped experience differs from the prototype, it is rarely because engineers are careless. It is usually because trade offs were made under time, performance, or integration pressure, and if design is not present when those trade offs are made, it forfeits the right to be surprised by the outcome. Teams solve problems every day while constraints shift, dependencies fail, budgets tighten, and deadlines loom. Without skin in the game, without a seat in the room, without a detailed understanding of constraints and trade offs, commentary becomes heckling, and heckling improves nothing.

5. Cyber as a Backlog Generator

Cyber and security teams can drift into the same pattern. A penetration test report is not value. A spreadsheet of findings is not protection. A quarterly email with severity ratings is not security. If the same issues reappear release after release, the problem is not developer immaturity. It is systemic enablement.

A cyber team that works with platform teams to harden pipelines, embeds guardrails into CI CD, provides reusable components to prevent entire classes of vulnerability, and supplies consumable building blocks which make the secure path the easiest path is a team creating value. If instead you hand delivery teams a list of findings and walk away, you are not reducing risk, you are generating a backlog item competing for priority against revenue, customer experience, and regulatory change. Give teams tools that solve real problems and they will use them. Give them a list of issues and you will be negotiated.

6. The PMO Spectator Effect

There is a special flavour of corporate heckling reserved for the PMO.

On paper, the Project Management Office exists to create predictability, reduce risk, and improve transparency across portfolios. It promises discipline, visibility, and control. In theory, it should be an accelerant.

In practice, when it drifts into commentary, it becomes a narrator of delivery rather than an enabler of it. A heckling PMO produces immaculate status reports while delivery teams wrestle with messy reality. It tracks milestones but does not remove blockers. It escalates risk but does not help redesign plans. It enforces process compliance but does not materially improve outcomes.

Because PMOs rarely own the product or the technical architecture, they can afford to construct clean narratives about what “should” have happened. They can question estimates without absorbing integration complexity. They can demand alignment without carrying the cost of delay. They can score maturity without understanding constraints. The result is governance theatre.

Product teams, meanwhile, are balancing client needs, technical debt, regulatory nuance, and commercial trade offs. They have already considered most of the counter proposals. They have already debated alternatives. But they have less energy to defend their position because they are also trying to ship. Eventually alignment sessions are scheduled. Decks are exchanged. Language is harmonised. Both sides present. Both sides moderate. Both sides leave with a shared document that looks like consensus but mostly reflects exhaustion.

And nothing changes. The product continues largely as it was. The heckler moves to the next target. The only casualty is the energy quietly consumed by the whole exercise, energy that was never measured, never recovered, and never missed until you wonder why the organisation always feels slightly slower than it should.

A high value PMO would look very different. It would embed in delivery. It would focus on unblocking rather than reporting. It would simplify rather than add ceremony. It would help teams make trade offs instead of policing them. If the PMO’s primary output is narrative about other teams, it is heckling. If its output is accelerated delivery, fewer surprises, and clearer decisions, it is leadership.

7. Narrative Is Not Delivery

Every function in an organisation must produce something more than a narrative about another team. Architecture must produce principles and platforms that reduce friction. Risk must produce insight that shapes decisions in real time. UX must produce clarity that survives contact with engineering. Cyber must produce systems that prevent recurrence. If your primary output is a deck explaining why others are not good enough, you are not creating value. You are heckling. Delivery teams do not need more commentary. They need partners who share accountability for outcomes.

8. The Seductive Counter Narrative

There is a more insidious dimension to corporate heckling that deserves its own examination.

Because the heckler carries almost no production responsibility, they have something the product team does not: spare capacity for narrative construction. They can spend days crafting a compelling alternative story. A cleaner model. A simpler approach. A vision unburdened by the complexity of actually having to deliver it. And it is often seductive. It sounds coherent. It has diagrams. It has a name. What it rarely has is memory.

On inspection, product teams have almost always already considered this narrative. They have interrogated it, tested it against their client data, weighed it against constraints the heckler has never encountered, and made a deliberate choice to move in a different direction. They understand their clients better. They have a plan. They simply did not write a deck about the roads they chose not to take.

The asymmetry is damaging. The heckler, unencumbered by delivery, can invest disproportionate energy in articulating their counter narrative. The product team, already running a business and trying to ship value, has far less energy to defend decisions they made correctly but informally. The burden of proof falls on the wrong party.

So organisations do what they always do when two competing narratives collide. They force alignment. They convene workshops. They create working groups. They schedule steering forums. Both sides present. Both sides moderate. Both sides leave with a shared document that looks like consensus but mostly reflects exhaustion. And nothing changes. The product continues largely as it was. The heckler moves to the next target. The only casualty is the energy quietly consumed by the whole exercise, energy that was never measured, never recovered, and never missed until you wonder why the organisation always feels slightly slower than it should.

Counter narratives produced without delivery accountability are not strategy. They are expensive theatre dressed as governance.

9. The Bar Raiser Is Not a Heckler

It is worth being precise about what this essay is not arguing. It is not arguing against challenge. It is not arguing against tension. It is not arguing that product teams should be left alone to make decisions in comfortable isolation. Unchallenged teams drift. Comfortable consensus produces mediocre outcomes. Tension, applied well, is one of the most productive forces in any organisation. The bar raiser is the embodiment of this distinction.

A bar raiser is not a commentator. They are a subject matter expert with a proven track record, someone who has run production workloads at comparable scale, who has felt the weight of the trade offs, who has made the hard calls under pressure and lived with the consequences. They do not arrive with a pre formed narrative. They arrive with hard won pattern recognition and the credibility that comes from having delivered.

Critically, they sit inside the team. They attend the same discovery sessions. They read the same constraints. They understand the client problems before they form an opinion about the solution. Their challenge comes after comprehension, not before it. Their narrative is built collaboratively, through conversation, through disagreement grounded in shared context, through tension that makes the output stronger rather than simply louder.

This is what separates the bar raiser from the heckler. The heckler’s narrative precedes understanding. The bar raiser’s narrative emerges from it. The heckler creates two competing stories and forces an alignment process that exhausts both sides. The bar raiser creates one shared story, harder won, more durable, and owned by the people who have to deliver it.

But calling something a bar raising session does not make it so. The label is not the thing. If you want to know whether your bar raising function is actually raising the bar, ask the teams that attended. Ask them whether it added value. Ask whether any outcomes improved as a result. Ask whether they spent the session restating constraints to ideas that were not sufficiently thought through before the meeting was called. Ask whether they left with genuine assistance or with a list of issues to resolve on their own. The answers will tell you quickly whether you have a bar raiser or an institutionalised heckler with a better job title.

Challenge without context is noise. Challenge with context, delivered from inside the work, is how good teams become great ones.

10. What To Do If You Have Heckling Functions

If you recognise these patterns in your organisation, the instinct may be to restructure, defund, or simply ignore the offending functions. That instinct is understandable but wrong, because it wastes the expertise that almost certainly exists inside those teams.

The people in these functions are not usually incompetent. Many of them are deeply skilled, experienced, and genuinely want to make a difference. The problem is structural. They have been placed at a distance from delivery, given frameworks instead of problems, and measured on outputs that have nothing to do with what actually ships. Over time, commentary becomes the only currency available to them. It is not surprising that frustration follows. They sense their own irrelevance. They feel the distance growing between their work and anything that matters. The heckling is often a symptom of that frustration, not its cause.

No organisation can afford teams whose relevance depends on someone else’s product set. That is not a support function. That is a dependency masquerading as governance. When a team’s purpose is defined by what another team is building rather than by what they themselves are accountable for delivering, they will always drift toward commentary. They have no other move. Their existence requires the product team to be doing something they can talk about.

The solution is reintegration. Move architects into delivery teams. Embed risk practitioners into sprint ceremonies. Put UX designers in the room when engineering trade offs are being made. Give cyber teams ownership of platform controls rather than audit findings. Make them accountable for outcomes they can actually influence, not scores on a maturity model that no one trusts. And if a team cannot articulate what it produces independently of what another team is building, that is not a communication problem. It is a mandate problem that no amount of heckling will solve.

Most people, given the chance to do real work and contribute to something that ships, will take it. The commentariat is not a permanent condition. It is what happens when talented people are structurally prevented from being useful. Reintegrate them, give them genuine accountability, and most of them will stop narrating and start building.

Corporate heckling is loud, confident, and useless. The bar raiser is quiet, credible, and transformative. Collaboration is harder than commentary, and slower to begin, but it is the only thing that actually compounds. One builds decks. The other builds outcomes.