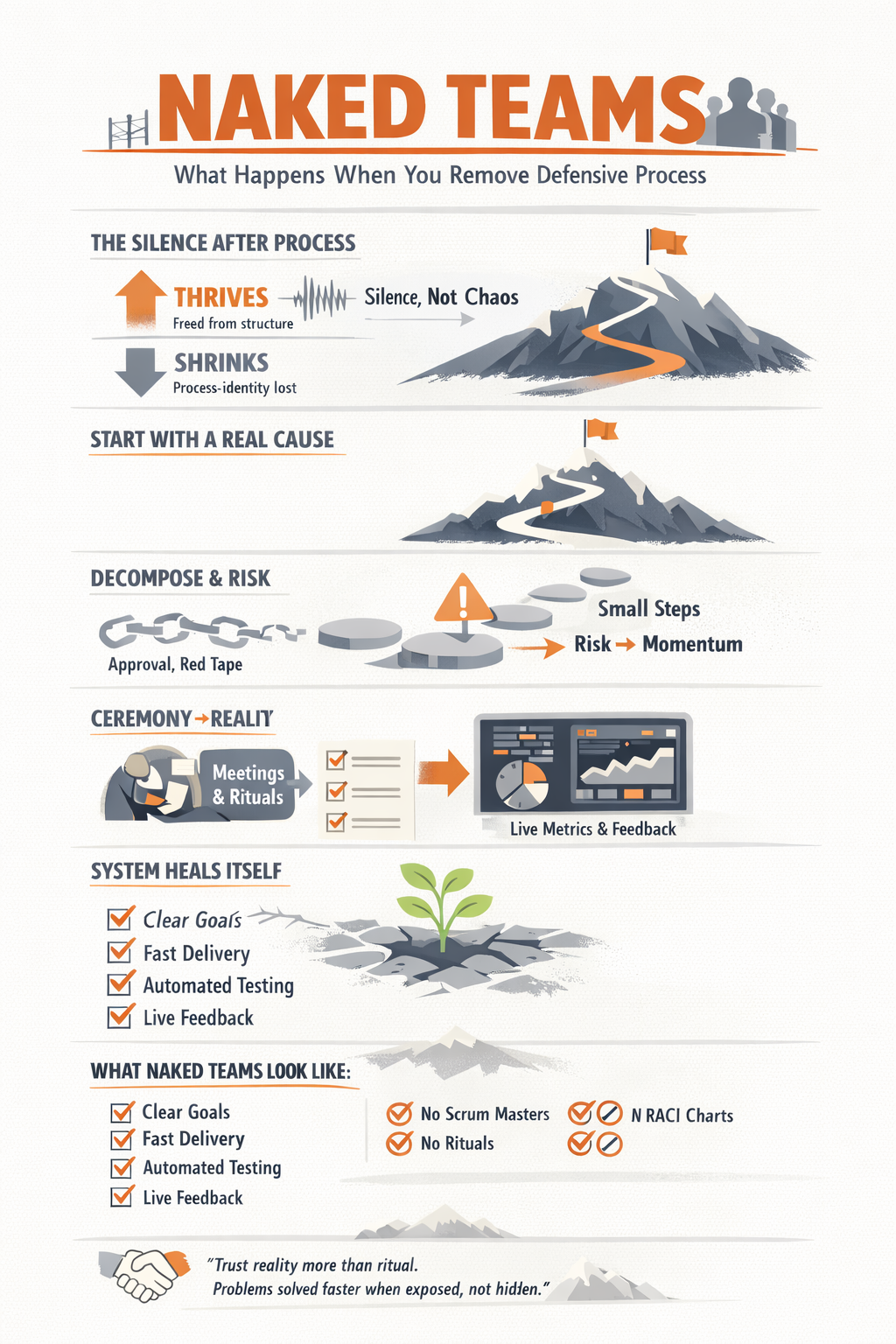

1. The Uncomfortable Silence After the Music Stops

Every organisation that runs on defensive process has a soundtrack. Standups hum at 9am. Sprint reviews crackle on Fridays. Retros generate their familiar low frequency guilt. Planning ceremonies fill the gaps. Remove all of it and the first thing you hear is silence, and silence in a corporate environment is terrifying because it forces a question that most people have been trained to avoid: what are we actually supposed to be doing?

The emotional response to stripping away process is never uniform. It splits immediately and the split is revealing. Some people come alive. These are the ones who were quietly suffocated by the scaffolding, who knew the ceremonies were theatre, and who had been carrying the frustration of watching real work get buried under administrative performance. For them, the silence is not emptiness. It is oxygen.

Others collapse inward. These are the process guardians, the people whose identity, authority, and daily structure were inseparable from the frameworks they administered. When the framework disappears, they do not lose a tool. They lose a role. They feel invalidated, exposed, and deeply vulnerable, and that vulnerability is real, not theatrical. These are often good people who built their careers around something the organisation told them mattered. It is not their fault that it didn’t.

Both reactions are valid. Both are present in every team simultaneously. And managing this emotional fracture without either dismissing it or drowning in it is the first real leadership challenge of building a naked team.

2. Nothing Is Sacred, but Not Everything Is Theatre

Before going any further, I need to correct a misreading that this kind of article invites. Stripping away defensive process is not the same as stripping away all process. That distinction is everything.

A feedback loop is a process. Design reviews are a process. Automated testing gates are a process. Architecture governance that forces domain isolation and creates evolutionary pressure on teams is an extraordinarily demanding process. None of these are removed. Many of them are improved, tightened, or introduced for the first time.

What gets removed is process that exists to defend the organisation from accountability rather than to improve outcomes. The difference is not always obvious from the outside, which is why you cannot approach this with a machete. You have to unpack what you are dismantling before you dismantle it. If you hack at processes without understanding what they are doing, you will disorientate the team and burn trust. If in doubt, leave the process in place and come back to it later. Oscillating destroys credibility faster than bad process ever could.

The principle is not elimination. The principle is that nothing is sacred and everything must earn its place. What survives is intentional. What is removed was not. And what replaces it is often more rigorous than what came before, just rigorous about different things.

3. Start With a Cause, Not a Structure

The instinct after removing process is to replace it with different process. Resist this completely.

The first thing a stripped back team needs is not a new framework, a new board, or a new set of rituals. It needs a cause. A reason to exist that is larger than the mechanics of how it operates. Specifically, it needs an Everest, a problem that the organisation has failed to solve, one that is existential or close to it, something big enough that the answer cannot be found inside the old ways of working because if it could, it would already be solved.

This is deliberate. You do not strip away process and then ask teams to do the same work they were doing before, just without the sticky notes. That creates a vacuum. You strip away process and then point at a mountain that nobody has been able to climb. The mountain provides the urgency. The urgency provides the structure. And the structure that emerges from genuine urgency looks nothing like the structure that was removed, because it is shaped by the problem rather than by organisational comfort.

4. Break the Mountain Into Steps and Take Risks to Get There

An Everest that remains monolithic is paralysing. The next move is decomposition, not into sprints or backlogs, but into short, deliverable steps where progress is visible and real. Each step should be achievable quickly enough that momentum builds before doubt sets in.

This is where risk enters the picture, and risk is the ingredient that process was specifically designed to eliminate. Defensive process exists to ensure that nothing unexpected happens. Naked teams exist to ensure that something does. You take calculated risks. You move faster than feels comfortable. You accept that not every step will land cleanly.

When things go wrong, and they will, they go small. The steps are short enough that failure is contained, visible, and recoverable. This is critical. The team needs to experience failure that does not destroy them. They need to see a leader who responds to a stumble by helping them stand up rather than convening a review board. Each small failure that is handled well builds more trust than any amount of success, because it proves that the new world is not a trap.

And when you score, and you will, the momentum is extraordinary. Teams that have been trapped inside defensive process for years have often forgotten what genuine progress feels like. The first real win, the first time something lands in production and makes a visible difference, is electric. It rewires the team’s relationship with work.

5. Exit Constraints Before You Assess Capability

Before you can evaluate what a team is capable of, you have to remove the constraints that are suppressing their capability. These constraints are often invisible to the team itself because they have been normalised.

The most common constraint I encounter is approval addiction. Teams believe they need sign offs from dozens of people before they can do anything. They create elaborate documentation not because it improves outcomes but because it provides air cover. They spend weeks seeking permission for work that should take days to execute. This entire apparatus exists to protect the organisation from blame, not to protect clients from failure.

On day one, I exit all of it. The question becomes simple: what are you trying to do and what evidence do you have that you will be successful? That is the only gate. If the evidence is strong, move. If it is weak, strengthen it. No committee required.

But removing approval culture is not the same as removing standards. This distinction matters and getting it wrong is how simplification becomes recklessness. I look at a team’s track record in executing change. If it is poor, I block them from production until they meet an agreed testing bar. We then rebuild their test environments, create automated testing scripts, and establish a path to production that is engineered rather than governed. The constraint shifts from human approval to technical evidence. The bar does not drop. It moves from bureaucratic to empirical.

Other constraints vary. Funding structures that prevent movement. Compliance requirements that have calcified into ritual. Infrastructure that makes deployment a three week event. Shared services that respond on geological timescales. My first job is to identify and exit every constraint that stands between the team and the mountain. My second job is to assess what we are actually working with once those constraints are gone.

Teams often carry a piano on their back and wonder why they are struggling. My job is to allow them to leave it behind.

6. There Is No Such Thing as an Immature Team

The technology industry is addicted to maturity models. Teams are assessed, scored, and categorised. Low maturity teams receive more governance. High maturity teams receive more freedom. The model feels rational and fair. It is neither.

Maturity is a leadership excuse to treat some teams worse than others. I do not believe teams are immature as such. They can be inexperienced or misdirected, but the word maturity implies a fixed state, a ceiling, a reason to wait. Every team I have ever worked with had the potential to be successful. The question was never whether they could get there. The question was what was preventing them from getting there, and the answer was almost always one of two things: the leadership above them or one or two individuals inside them.

Sometimes the answer is to add engineering skills and weaken management structures. Sometimes it is the reverse. Sometimes a team needs extreme structure applied selectively to solve a chronic weakness, and in those cases I apply it without hesitation. The point is not that structure is always bad. The point is that the prescription must fit the condition, and the condition is almost never “the team is immature.” It is almost always “the team has been poorly led, poorly composed, or poorly directed.”

This matters because maturity models let organisations defer responsibility. If the team is immature, it is the team’s problem. If the team is misdirected, it is a leadership problem. The distinction determines where the fix lands, and maturity models reliably land it in the wrong place.

I never use a fixed approach. The principles are similar each time, but the application varies. What I can say is that you start to spot patterns with the types of failures, and they almost always stem from the top, not the bottom.

7. Replace Ceremony With Reality

Once you remove standups, sprint reviews, retrospectives, and burndown charts, you need something in their place. Not a lighter ceremony. Not a more agile version of agile. You need reality.

At Capitec, we built something called ELS, our Error Logging Service. Every single time a product team presents a client with a generic error screen, a “something went wrong” moment, the system records it. Not in a log file that nobody reads. Not in a dashboard that gets reviewed once a quarter. It records it immediately, in detail, and surfaces it to the teams responsible.

Each error generates a diagnostic ticket. An AI model running on AWS Bedrock analyses the HTTP request chain, identifies the root cause, and produces a structured assessment that tells you exactly what failed and why. A profile service returning a status code zero at the fifth step of a Send Cash transaction is not ambiguous. It is a network connectivity failure or a service outage at a specific endpoint, and the diagnostic says so within seconds.

The summary view groups errors by frequency and page. When your domain is generating 800 errors per hour and the entire organisation can see which pages are failing and how often, there is no need for a scrum master to tell you how your sprint is going. Your clients are telling you directly, at machine speed.

This is what replaces ceremony. Not a different meeting. Not a better board. A system that makes reality unavoidable. Burndown charts measure compliance with a plan. ELS measures whether clients are suffering. Teams do not need to be told to act when they can see, in real time, that they are failing the people they exist to serve.

The feedback loop must be functioning, not performative. Praise alone is not enough. Progress must be visible to the team itself, not reported upward through a chain of status updates. When teams can see their own impact, directly and immediately, the motivation problem disappears. You do not need to manufacture urgency when reality provides it.

8. Let the System Heal Itself

The hardest discipline for a leader in this environment is restraint.

When the old process is removed and the process guardians are sitting in their discomfort, the temptation is to intervene, to coach, to reassure, to manage each person through the transition individually. I deliberately do not do this. I allow the person to sit in their emotions and to observe what is happening around them.

What I attack is what was created under their watch, not the person who created it. I focus relentlessly on speed, simplicity, and quality. I demonstrate through action what the new standard looks like, and then I watch each person’s response.

Teams, when trusted, create their own order. They heal. The people with genuine capability find new footing because the new environment rewards contribution rather than compliance. The people who were hiding behind process are revealed, but not by me. They are revealed by the contrast between what was and what is now possible.

My role in this phase is to acknowledge progress and actively encourage risk taking. I do not do individual coaching sessions with large teams. I take large groups on together and let the group dynamic do the work. That said, people do come to speak with me individually, and I am always happy to share, to open up, and to reassure where necessary. The door is open but I do not push anyone through it.

I have almost never had to fire or dismiss anyone through this process. People either find their place in the new order or they self select out. I do not believe in fear as a motivational tool. I do not like grovelling, performative loyalty, or leadership praise. We are all just humans doing work, and nobody is special, including me.

9. The Transition Is Not Cold Turkey

A reasonable question at this point is whether stripping away process means walking into a room on Monday morning and announcing that everything the team has known for the last five years is cancelled. The answer is no, and doing that would be as dogmatic as the frameworks being replaced.

Most people who work inside Agile ceremonies do not have a religious attachment to them. A process is just a process, and when something more efficient and more honest replaces it, most people transition quickly and with visible relief. If someone wants to keep their work in Jira because that is how they organise their thinking, I genuinely do not care. The tool is not the problem. The problem is when the tool becomes the thinking, when creativity and judgment are anchored in process dogma rather than freed by it.

The people who struggle most are not the ones who used Agile. They are the ones who became Agile. People who have invested years attending conferences, collecting certifications, and building an identity around a methodology will experience its removal as an existential threat. Their grasp on it is so strong that letting go feels like losing themselves. I have empathy for this, but I cannot let it govern the pace of change. What I can do is give people space to make the adjustment, and most of them do.

The transition works because the replacement is visible. When teams start climbing, when errors drop, when clients are better served, and when the evidence is undeniable, most process attachment dissolves on its own. You do not need to argue people out of a belief system. You need to show them something better.

10. The Personal Cost of Doing This at Scale

There is a version of this story that ends cleanly. One team, six to twelve months, a visible transformation, everyone learns and grows. I have done that version and it works beautifully.

Then there is the version I lived through at Capitec after the 40 hour outage that was widely reported in the South African media. I looked at the scale of what needed to change and I took on too much at once. Not one team. Twelve teams in eighteen months. Multiple large problems running in parallel, each demanding the same intensity, the same presence, the same emotional labour.

It was personally very painful. It made me unwell. My family suffered.

I am not going to reframe this as a learning experience or extract a tidy lesson about pacing and boundaries. I do not allow retrading. I made the best call at that point in time with everything I knew. I could have pivoted and I chose not to. Therefore I trust that the version of me who woke up each morning made the right calls with the information available on that day.

If you ask me what I would have done differently, the answer is nothing, unless I had a crystal ball, in which case I would not need to work in the first place.

The cost was real. I paid it. The teams are better. The systems are better. The clients are better served. Whether the price was right is not a question I am interested in answering retrospectively.

11. What Naked Teams Actually Look Like

A naked team, fully formed, does not look chaotic. It looks calm. It has a clear domain. It has a direct path to production. It has automated testing that provides confidence without requiring human approval chains. It has real time visibility into how it is serving its clients. It has a mountain it is climbing and it can see the progress it is making.

It does not have a scrum master, a sprint cadence, a burndown chart, or a retrospective. It does not have a 97 slide deck explaining its operating model. It does not have a RACI matrix.

What it has is ownership that was earned through action rather than declared through governance. What it has is speed that comes from engineering rather than from frameworks. What it has is quality that is enforced by machines rather than by meetings.

The silence that was terrifying in week one becomes the sound of a team that knows exactly what it is doing and does not need to perform the act of knowing it.

12. Conclusion: Stripping Back Is Not Destruction

Removing defensive process is not an act of destruction. It is an act of trust. Trust that the people in the team have capability that was suppressed. Trust that reality, made visible, is a better motivator than ceremony. Trust that problems, honestly confronted, get solved faster than problems wrapped in governance.

It is also an act of discernment. Not everything gets removed. What survives is intentional. What is added is deliberate. What is removed was never earning its place. The rigour does not decrease. It changes shape, from performative to empirical, from ceremonial to engineered, from defensive to honest.

The piano was never helping them climb. It was just heavy, familiar, and nobody had given them permission to put it down.

Give them the permission. Point at the mountain. And then get out of the way.