1. The Dead Giveaway Is the Meeting Itself

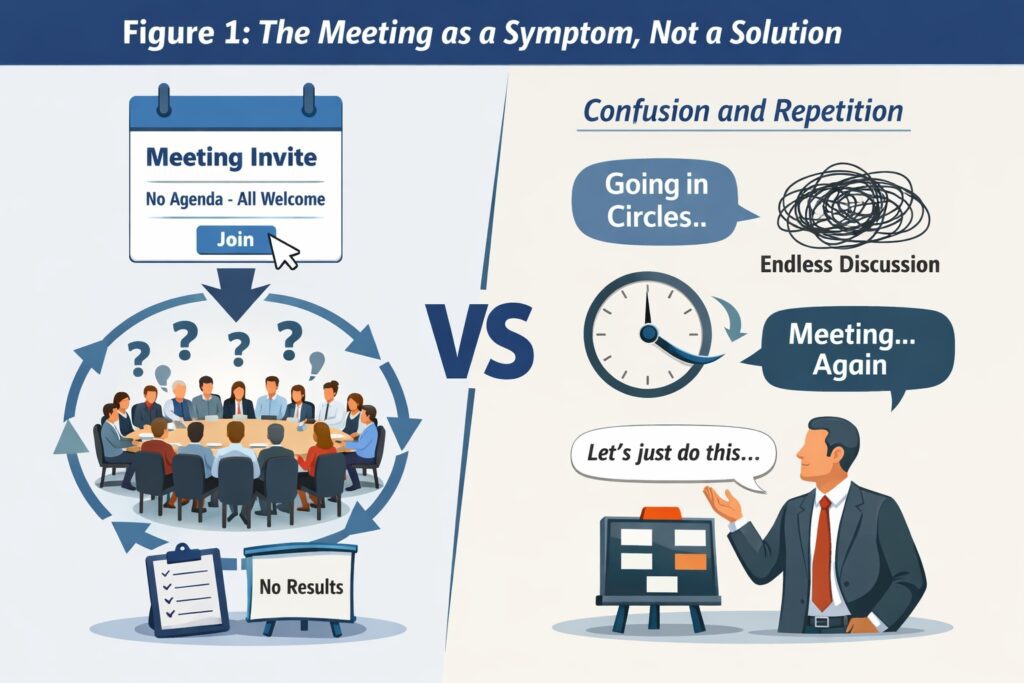

There is a reliable early warning signal that corporate herding is about to occur: the meeting invite.

No meaningful agenda. No pre reading. No shared intellectual property. No framing of the problem. Just a vague title, an hour blocked out, and a distribution list that looks like someone ran out of courage before removing names.

When a room is “full of anyone and everyone we could think to invite”, it is not because the problem is complex. It is because nobody has done the work required to understand it and consider who can make a meaningful contribution.

Meeting are not the place where thinking happens, they are the place thinking is avoided.

2. Herding Disguised as Collaboration

The stated intent is always noble. “We want alignment.” “We want buy in.” “We want everyone’s input.” In practice, this is herding behaviour dressed up as inclusivity.

Thirty people arrive with different mental models, incentives, and levels of context. Nobody owns the problem. Nobody has written anything down. Discussion ricochets between anecdotes, opinions, and status updates. Action items are vague. The same meeting is scheduled again.

Eventually, exhaustion replaces analysis. A senior person proposes something, not because it is correct, but because the room needs relief. The solution is accepted by attrition.

This is not decision making. It is social fatigue.

3. Why the Lack of Preparation Matters

The absence of upfront material is not accidental. It is structural.

Writing forces clarity. Writing exposes gaps. Writing makes assumptions visible and therefore debatable. Meetings without pre work allow people to appear engaged without taking intellectual risk.

No agenda usually means no problem statement.

No shared document usually means no ownership.

No proposal usually means no thinking has occurred.

When nothing is written down, nothing can be wrong. That is precisely why this pattern persists.

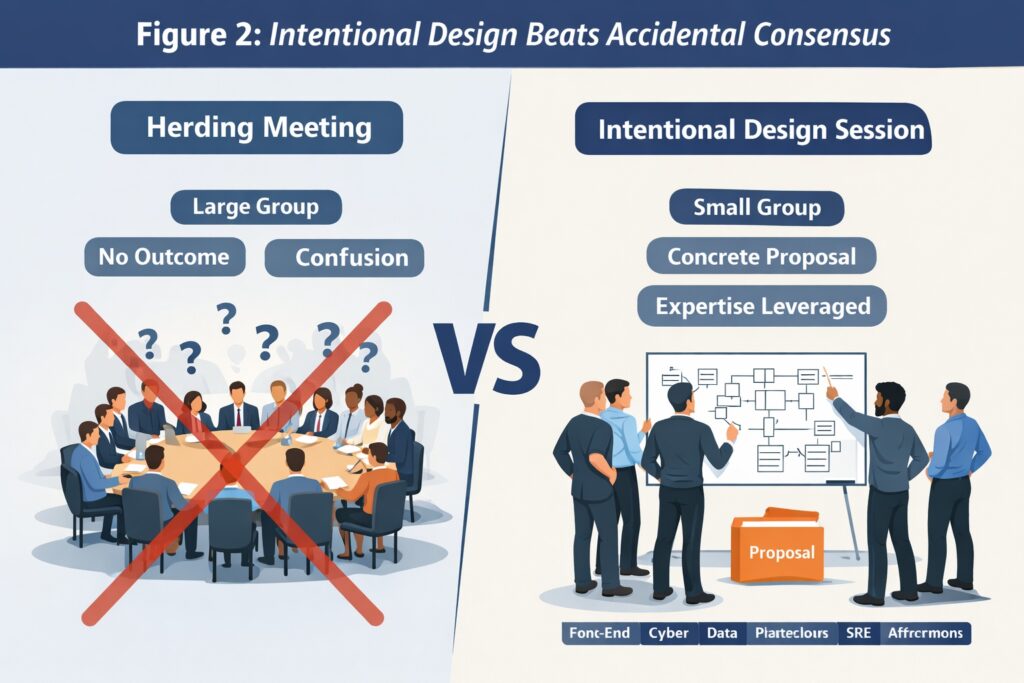

4. The Intentional Alternative

Contrast this with an intentional design session.

Half a dozen deliberately chosen engineers. Front end. Backend. Data. Cyber. SRE. Platform. UX Designers. The people whose job it is to understand constraints, not just opinions.

They arrive having already thought. They draw. They argue. They model failure modes. They leave with something concrete: an architecture sketch, a proposal, a set of tradeoffs that can be scrutinised.

This is not about excluding people. It is about respecting expertise and time.

5. Buy In Is Still Not a Design Input

Herding meetings are often justified as necessary to “bring people along”. This is backwards.

You do not earn buy in by asking everyone what they think before you have a proposal. You earn buy in by presenting a clear, well reasoned solution that people can react to. A proposal invites critique. A meeting without substance invites politics.

If your process requires pre emptive consensus before thinking is allowed, you are guaranteeing weak outcomes.

6. What Meetings Are Actually For (And What They Are Not)

Most organisations misuse meetings because they have never been explicit about their purpose.

A meeting is not a thinking tool. It is not a design tool. It is not a substitute for preparation. Meetings that are there purely for updates can easily be replaced by a Whatsapp group. When meetings are used in such frivolous ways, they become expensive amplifiers of confusion and they signal to staff: “We don’t care what you spend your time on; as long as you’re busy!”.

Meetings are for review, decision making, and coordination. They are not for first contact with a problem. If nobody has written anything down beforehand, the meeting has already failed.

The Diary Excuse Is a Dead End

When you ask attendees what the agenda is, or what ideas they are bringing, you will often hear the same response:

“This is just the first meeting we could get in everyone’s diary.”

This is the tell.

What this really means is that nothing has been done for weeks while people waited for senior availability. Thinking has been deferred upward. Responsibility has been paused until titles are present.

The implicit belief is that problems are solved by proximity to senior people, not by effort or clarity. So instead of doing groundwork, people wait. And wait. And then book a meeting.

If you then ask what they are doing for the rest of the day, the answer is almost always:

“I’m back to back all day.”

Busy, but inert. This is how organisations confuse calendar saturation with productivity.

What Meetings Are For

Meetings work when they operate on artifacts, not opinions.

A good meeting typically does one of three things:

- Reviews a written proposal or design and challenges assumptions.

- Makes an explicit decision between clearly defined options.

- Coordinates execution once direction is already set.

In all three cases, the thinking has happened before people enter the room. The meeting exists to compress feedback loops, not to discover reality in real time.

This is why effective meetings feel short, sometimes uncomfortable, and often decisive.

What Meetings Are Not For

Meetings should not be used to:

- Define the problem for the first time

- Gather raw, unstructured ideas from large groups

- Wait for senior people to think on behalf of others

- Achieve emotional comfort through alignment

- Signal progress in the absence of substance

If the primary output of a meeting is “we need another meeting”, then the meeting was theatre, not work.

Large, agenda-less meetings are especially dangerous because they allow people to avoid accountability while appearing busy.

A Simple Time Discipline Most Companies Ignore

As a rule, everyone in a company except perhaps the executive committee should not spend more than half their time in meetings.

If your calendar is wall to wall, you are not collaborating. You are unavailable for actual work.

Most meetings do not require a meeting at all. They can be replaced with:

- A short written update

- A WhatsApp message/group

- A document with comments enabled

If something does not require real-time debate or a decision, synchronous time is wasteful.

A Rule That Actually Works

The rule is straightforward:

If the problem cannot be clearly explained in writing, it is not ready for a meeting. If there is no agenda, no shared document, and no explicit decision to be made, decline the meeting.

This does not slow organisations down. It speeds them up by forcing clarity upstream and reserving collective time for moments where it actually adds value.

Meetings should multiply the value of thinking, not replace it.

My Personal Rule

My default response to meetings is no. Not because I dislike collaboration, but because I respect thinking and time is more finite that money. If there is no written problem statement, no agenda, and no evidence of prior effort, I will decline and ask for groundwork instead. I am happy to review a document, challenge a proposal, or make a decision, but I will not attend a meeting whose purpose is to discover the problem in real time or wait for senior people to think on behalf of others. Proof of life comes first. Meetings come second.

7. Workshops as a Substitute for Thinking

One of the more subtle failure modes is the meeting that rebrands itself as a workshop.

The word is used to imply progress, creativity, and action. In reality, most so called workshops are just longer meetings with worse discipline.

A workshop is not defined by sticky notes, breakout rooms, or facilitators. It is defined by who did the thinking beforehand.

When a Workshop Is Legitimate

A workshop earns the name only when all of the following are true:

- A clearly written problem statement has been shared in advance

- Constraints and non negotiables are explicit

- One or more proposed approaches already exist

- Participants have been selected for expertise, not representation

- The expected output of the session is clearly defined

If none of this exists, the session is not a workshop. It is a brainstorming meeting.

What Workshops Are Actually For

Workshops are useful when you need to:

- Stress test an existing proposal

- Explore tradeoffs between known options

- Resolve specific disagreements

- Make irreversible decisions with high confidence

They are effective when the space of ideas has already been narrowed and the goal is depth, not breadth.

What Workshops Are Commonly Used For Instead

In weaker organisations, workshops are used to:

- Avoid writing anything down

- Create the illusion of momentum

- Distribute accountability across a large group

- Replace thinking with facilitation

- Manufacture buy in without substance

Calling this a workshop does not make it productive. It just makes it harder to decline.

A Simple Test

If a “workshop” can be attended cold, without pre reading, it is not a workshop.

If nobody would fail the session by arriving unprepared, it is not a workshop.

If the output is another workshop, it is not work.

Workshops should deepen thinking, not substitute for it.

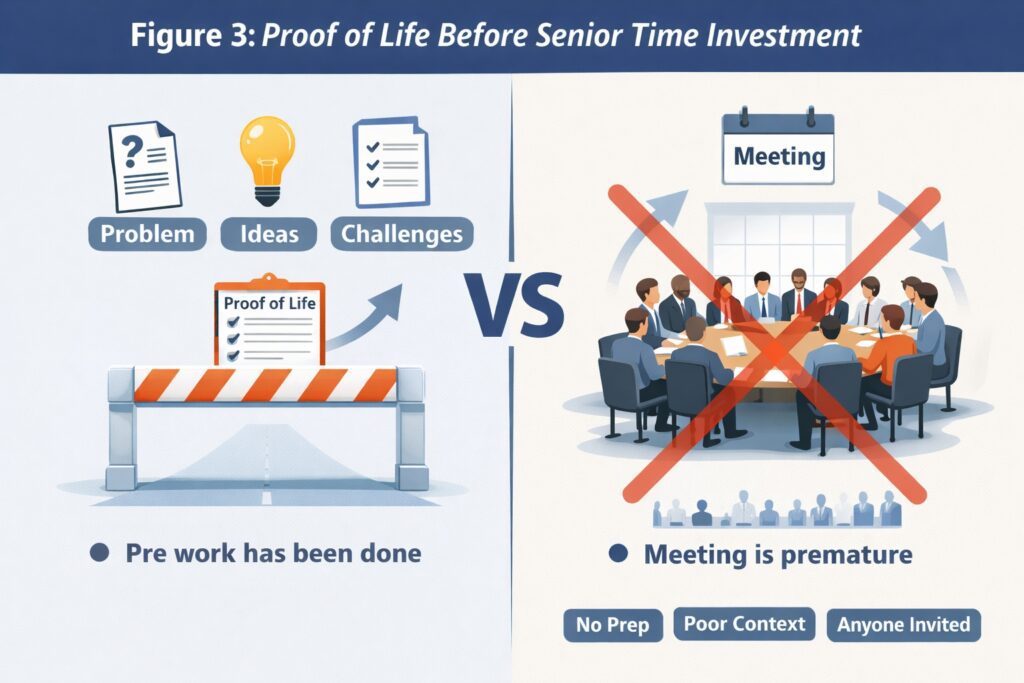

8. Why I Don’t Attend These Meetings

I actively discourage this pattern by not attending these meetings. This is not disengagement. It is a signal.

I will not invest my time in a room where nobody has invested theirs beforehand. I am not there to help people discover the problem in real time. That work is cheap individually and expensive collectively.

Before hauling thirty people into a Teams call or a boardroom, do the groundwork. Write down:

- What the actual problem is

- Why it matters

- What makes it hard

- What ideas have already been considered

- Where you are stuck

I do not need perfection. I need proof of life.

9. Proof of Life as a Professional Standard

A proof of life can be a short document. A rough PRFAQ. A few diagrams. Bullet points are fine. Wrong answers are fine. Unfinished thinking is fine.

What is not fine is outsourcing thinking to a meeting.

When there is written material, I can engage deeply. I can challenge assumptions. I can add value. Without it, the meeting is just a time sink with better catering.

10. What Actually Blocks This Behaviour

The resistance to doing pre work is rarely about time. It is about exposure.

Writing makes you visible. It makes your thinking criticisable. Meetings spread responsibility thin enough that nobody feels individually accountable.

Herding is safer for status and feelings. Design is safer for outcomes. Do you care about status or outcomes?

Organisations that optimise for protecting people’s status and feelings, will drift toward herding. Organisations that optimise for solving problems will force design.

Organisations that cannot tolerate early disagreement end up with late stage failure. Organisations that penalise people for speaking clearly or challenging ideas teach everyone else to pretend to agree instead of thinking properly.

As a simple test, in your next meeting propose something absolutely ridiculous and see if you can get buy in based purely on your seniority. If you can, you have a problem! I have had huge fun with this…

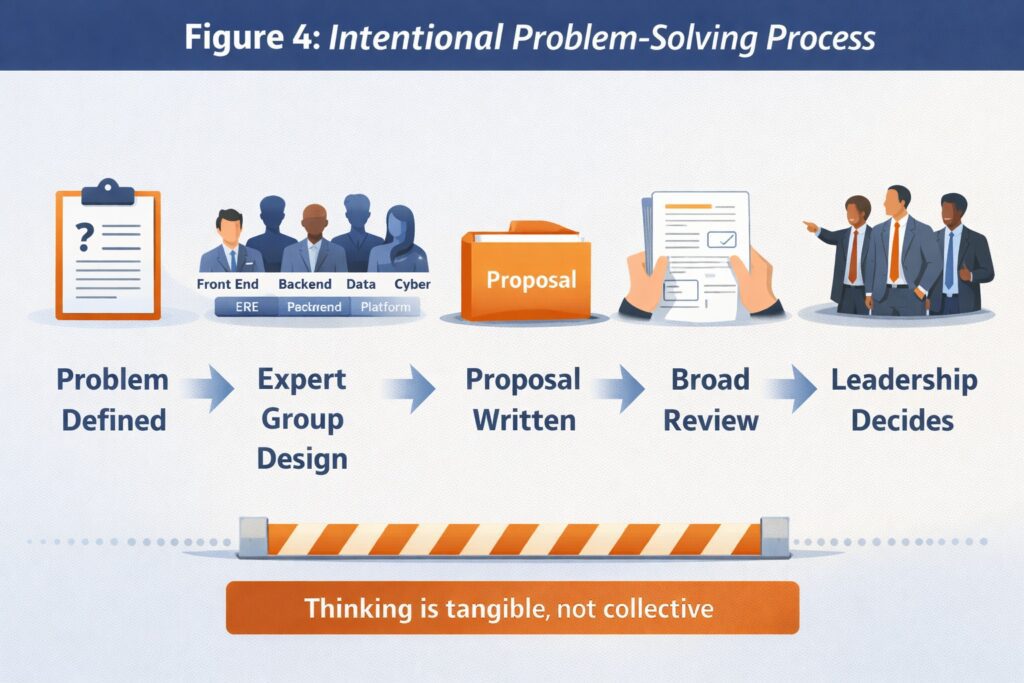

11. A Better Pattern to Normalise

The pattern worth institutionalising is simple:

- One or two people own the problem.

- A small expert group designs a solution.

- A written proposal or PRFAQ is produced.

- This is shared widely for feedback, not authorship.

- Leadership decides explicitly.

Meetings become review points, not thinking crutches.

12. The Challenge

If your default response to uncertainty is to book a meeting with everyone you know, you are not collaborating. You are deferring responsibility.

The absence of an agenda, the lack of pre reading, and the size of the invite list are not neutral choices. They are signals that thinking has not yet occurred.

Demand a proof of life. Reward intentional design. Stop mistaking movement for progress. That is how organisations get faster, not busier.