I wanted to write about the trends we can see playing out, both in South Africa and globally with respect to: Large Retailers, Mobile Networks, Banking, Insurance and Technology. These thoughts are my own and I am often wrong, so dont get too excited if you dont agree with me 🙂

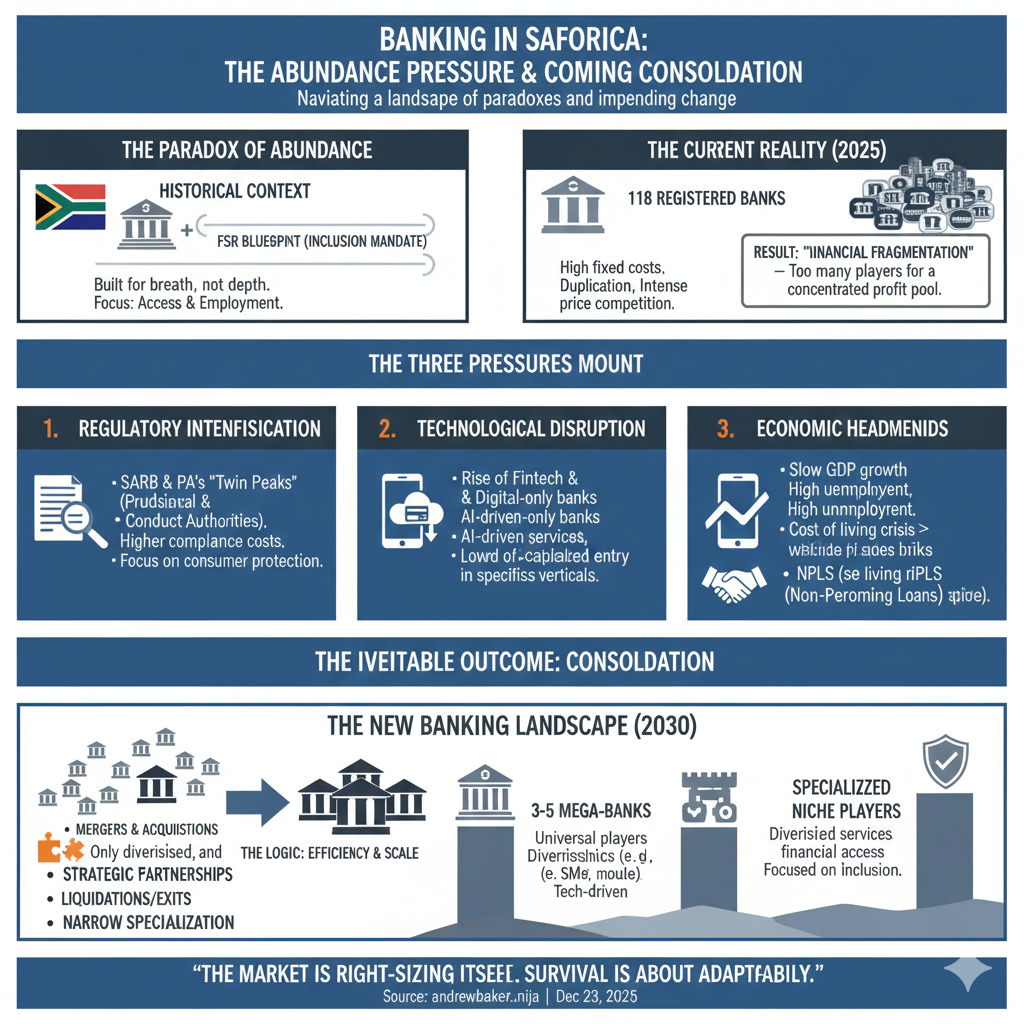

South Africa is experiencing a banking paradox. On one hand, consumers have never had more choice: digital challenger banks, retailer backed banks, insurer led banks, and mobile first offerings are launching at a remarkable pace. On the other hand, the fundamental economics of running a bank have never been more challenging. Margins are shrinking, fees are collapsing toward zero, fraud and cybercrime costs are exploding, and clients are fragmenting their financial lives across multiple institutions.

This is not merely a story about digital disruption or technological transformation. It is a story about scale, cost gravity, fraud economics, and the inevitable consolidations.

1. The Market Landscape: Understanding South Africa’s Banking Ecosystem

Before examining the pressures reshaping South African banking, it is essential to understand the current market structure. As of 2024, South Africa’s banking sector remains concentrated among a handful of large institutions. Together with Capitec and Investec, the major traditional banks held around 90 percent of the banking assets in the country.

Despite this dominance, the landscape is shifting. New bank entrants have gained large numbers of clients in South Africa. However, client acquisition has not translated into meaningful market share. This disconnect between client numbers and actual banking value reveals a critical truth: in an abundant market, acquiring accounts is easy. Becoming someone’s primary financial relationship is extraordinarily difficult.

2. The Incumbents: How Traditional Banks Face Structural Pressure

South Africa’s traditional banking system remains dominated by large institutions that have built their positions over decades. They continue to benefit from massive balance sheets, regulatory maturity, diversified revenue streams including corporate and investment banking, and deep institutional trust built over generations.

However, these very advantages now carry hidden liabilities. The infrastructure that enabled dominance in a scarce market has become expensive to maintain in an abundant one.

2.1 The True Cost Structure of Modern Banking

Running a traditional bank today means bearing the full weight of regulatory compliance spanning Basel frameworks, South African Reserve Bank supervision, anti money laundering controls, and know your client requirements. It means investing continuously in cybersecurity and fraud prevention systems that have evolved from control functions into permanent warfare operations. It means maintaining legacy core banking systems that are expensive to operate, difficult to modify, and politically challenging to replace. It means supporting hybrid client service models that span physical branches, call centres, and digital platforms, each requiring different skillsets and infrastructure.

Add to this the ongoing costs of card payment rails, interchange fees, and cash logistics infrastructure, and the fixed cost burden becomes clear. These are not discretionary investments that can be paused during difficult periods. They are the fundamental operating requirements of being a bank.

2.2 The Fee Collapse and Revenue Compression

At the same time that structural costs continue rising, transactional banking revenue is collapsing. Consumers are no longer willing to pay for monthly account fees, per transaction charges, ATM withdrawals, or digital interactions. What once subsidized the cost of branch networks and back office operations now generates minimal revenue.

This creates a fundamental squeeze where costs rise faster than revenue can be replaced. The incumbents still maintain advantages in complexity based products such as home loans, vehicle finance, large credit books, and business banking relationships. These products require sophisticated risk management, large balance sheets, and regulatory expertise that new entrants struggle to replicate.

However, they are increasingly losing the day to day transactional relationship. This is where client engagement happens, where financial behaviors are observed, and where long term loyalty is either built or destroyed. Without this foundation, even complex product relationships become vulnerable to attrition.

3. The Crossover Entrants: Why Retailers, Telcos, and Insurers Want Banks

Over the past decade, a powerful second segment has emerged: non banks launching banking operations. Retailers, insurers, and telecommunications companies have all moved into financial services. These players are not entering banking for prestige or diversification. They are making calculated economic decisions driven by specific strategic objectives.

3.1 The Economic Logic Behind Retailers Entering Banking

Retailers see five compelling reasons to operate banks:

First, they want to offload cash at tills. When customers can deposit and withdraw cash while shopping or visiting stores, retailers dramatically reduce cash in transit costs, eliminate expensive standalone ATM infrastructure, and reduce the security risks associated with holding large cash balances.

Second, they want to eliminate interchange fees by keeping payments within their own ecosystems. Every transaction that stays on their own payment rails avoids card scheme costs entirely, directly improving gross margins on retail sales.

Third, and most strategically, they want to control payment infrastructure. The long term vision extends beyond cards to account to account payment systems integrated directly into retail and mobile ecosystems. This would fundamentally shift power away from traditional card networks and banks.

Fourth, zero fee banking becomes a powerful loss leader. Banking services drive foot traffic, increase share of wallet across the ecosystem, and reduce payment friction for customers who increasingly expect seamless digital experiences.

Fifth, and increasingly the most sophisticated motivation, they want to capture higher quality client data and establish direct digital relationships with customers. This creates a powerful lever for upstream supplier negotiations that traditional retailers simply cannot replicate. Loyalty programs, whilst beneficial in respect of accurate client data, they typically fail to give you the realtime digital engagement needed to shift product. Most loyalty programs are either bar coded plastic cards or apps which have low client engagements and high drop off rates, principally due to their narrow value proposition.

Consider the dynamics this enables: a retailer with deep transactional banking relationships knows precisely which customers purchase specific product categories, their purchase frequency, their price sensitivity, their payment patterns, and their responsiveness to promotions. This is not aggregate market research. This is individualised, verified, behavioural data tied to actual spending.

Armed with this intelligence, the retailer can approach Supplier A with a proposition that would have been impossible without the banking relationship: “If you reduce your price by 10 basis points, we will actively engage the 340,000 customers in our ecosystem who purchase your product category. Based on our predictive models, we can demonstrate that targeted digital engagement through our banking app and payment notifications will double sales volume within 90 days.”

This is not speculation or marketing bravado. It is a data backed commitment that can be measured, verified, and contractually enforced.

The supplier faces a stark choice: accept the price reduction in exchange for guaranteed volume growth, or watch the retailer redirect those same 340,000 customers toward a competing supplier who will accept the terms.

Traditional retailers without banking operations cannot make this proposition credible. They might claim to have customer data, but it is fragmented, often anonymised, and lacks the real time engagement capability that banking infrastructure provides. A banking relationship means the retailer can send a push notification at the moment of payment, offer instant cashback on targeted products, and measure conversion within hours rather than weeks.

This upstream leverage fundamentally changes the power dynamics in retail supply chains. Suppliers who once dictated terms based on brand strength now find themselves negotiating with retailers who possess superior customer intelligence and the direct communication channels to act on it.

The implications extend beyond simple price negotiations. Retailers can use this data advantage to optimise product ranging, predict demand with greater accuracy, negotiate exclusivity periods, and even co develop products with suppliers based on demonstrated customer preferences. The banking relationship transforms the retailer from a passive distribution channel into an active market maker with privileged access to consumer behaviour.

This is why the smartest retailers view banking not as a side business or diversification play, but as strategic infrastructure that enhances their core retail operations. The banking losses during the growth phase are an investment in capabilities that competitors without banking licences simply cannot match.

3.2 The Hidden Complexity They Underestimate

What these players consistently underestimate is that banking is not retail with a license. The operational complexity, regulatory burden, and risk profile of banking operations differ fundamentally from their core businesses.

Fraud, cybercrime, dispute resolution, chargebacks, scams, and client remediation are brutally complex challenges. Unlike retail where a product return is a process inconvenience, banking disputes involve money that may be permanently lost, identities that can be stolen, and regulatory obligations that carry severe penalties for failure.

The client service standard in banking is fundamentally different. When a retail transaction fails, it is frustrating. When a banking transaction fails and money disappears, it becomes a crisis that can devastate client trust and trigger regulatory scrutiny.

The experience of insurer led banks illustrates these challenges with brutal precision. Building a banking operation requires billions of rand in upfront investment, primarily in technology infrastructure and regulatory compliance systems. Banks launched by insurers have operated at significant losses for several years while building scale. In a market already saturated with low cost options and fierce competition for the primary account relationship, the margin for strategic error is extraordinarily thin.

4. Case Study: Old Mutual and the Nedbank Paradox

The crossover entrant dynamics described above find their most striking illustration in Old Mutual’s decision to build a new bank just six years after unbundling a R43 billion stake in one of South Africa’s largest banks. This is not merely an interesting corporate finance story. It is a case study in whether insurers can learn from their own history, or whether they are destined to repeat expensive mistakes.

4.1 The History They Already Lived

Old Mutual acquired a controlling 52% stake in Nedcor (later Nedbank) in 1986 and held it for 32 years. During that time, they learned exactly how difficult banking is. Nedbank grew into a full service institution with corporate banking, investment banking, wealth management, and pan African operations. By 2018, Old Mutual’s board concluded that managing this complexity from London was destroying value rather than creating it.

The managed separation distributed R43.2 billion worth of Nedbank shares to shareholders. Old Mutual reduced its stake from 52% to 19.9%, then to 7%, and today holds just 3.9%. The market’s verdict: Nedbank’s market capitalisation is now R115 billion, more than double Old Mutual’s R57 billion.

Then, in 2022, Old Mutual announced it would build a new bank from scratch.

4.2 The Bet They Are Making Now

Old Mutual has invested R2.8 billion to build OM Bank, with cumulative losses projected at R4 billion to R5 billion before reaching break even in 2028. To succeed, they need 2.5 to 3 million clients, of whom 1.6 million must be “active” with seven or more transactions monthly.

They are launching into a market where Capitec has 24 million clients, TymeBank has achieved profitability with 10 million accounts, Discovery Bank has over 2 million clients, and Shoprite and Pepkor are both entering banking. The mass market segment Old Mutual is targeting is precisely where Capitec’s dominance is most entrenched.

The charitable interpretation: Old Mutual genuinely believes integrated financial services requires owning transactional banking capability. The less charitable interpretation: they are spending R4 billion to R5 billion to relearn lessons they should have retained from 32 years owning Nedbank.

4.3 The Questions That Should Trouble Shareholders

Why build rather than partner? Old Mutual could have negotiated a strategic partnership with Nedbank focused on mass market integration. Instead, they distributed R43 billion to shareholders and are now spending R5 billion to recreate a fraction of what they gave away.

What institutional knowledge survived? The resignation of OM Bank’s CEO and COO in September 2024, months before launch, suggests the 32 years of Nedbank experience did not transfer to the new venture. They are learning banking again, expensively.

Is integration actually differentiated? Discovery has pursued the integrated rewards and banking model for years with Vitality. Old Mutual Rewards exists but lacks the behavioural depth and brand recognition. Competing against Discovery for integration while competing against Capitec on price is a difficult strategic position.

What does success even look like? If OM Bank acquires 3 million accounts but most clients keep their salary at Capitec, the bank becomes another dormant account generator. The primary account relationship is what matters. Everything else is expensive distraction.

4.4 What This Tells Us About Insurer Led Banking

The Old Mutual case crystallises the risks facing every crossover entrant discussed in Section 3. Banking capability cannot be easily exited and re entered. Managed separations can destroy strategic options while unlocking short term value. The mass market is not a gap waiting to be filled; it is a battlefield where Capitec has spent 20 years building structural dominance.

Most importantly, ecosystem integration is necessary but not sufficient. The theory that insurance plus banking plus rewards creates unassailable client relationships remains unproven. Old Mutual’s version of this integrated play will need to be meaningfully better than Discovery’s, not merely present.

Whether Old Mutual’s second banking chapter ends differently from its first depends on whether the organisation has genuinely learned from Nedbank, or whether it is replaying the same strategies in a market that has moved on without it. The billions already committed suggest they believe the former. The competitive dynamics suggest the latter.

5. Fraud Economics: The Invisible War Reshaping Banking

Fraud has emerged as one of the most significant economic forces in South African banking, yet it remains largely invisible to most clients until they become victims themselves. The scale, velocity, and sophistication of fraud losses are fundamentally altering banking economics and will drive significant market consolidation over the coming years.

5.1 The Staggering Growth in Fraud Losses

The fraud landscape in South Africa has deteriorated at an alarming rate. Looking at the three year trend from 2022 to 2024, the acceleration is unmistakable. More than half of the total digital banking fraud cases in the last three years occurred in 2024 alone, according to SABRIC.

Digital banking crime increased by 86% in 2024, rising from 52,000 incidents in 2023 to almost 98,000 reported cases. When measured by actual cases rather than just value, digital banking fraud more than doubled, jumping from 31,612 in 2023 to 64,000 in 2024. The financial impact climbed from R1 billion in 2023 to over R1.4 billion in 2024, representing a 74% increase in losses year over year.

Card fraud continues its relentless climb despite banks’ investments in security. Losses from card related crime increased by 26.2% in 2024, reaching R1.466 billion. Card not present transactions, which occur primarily in online and mobile environments, accounted for 85.6% of gross credit card fraud losses, highlighting where criminals have concentrated their efforts.

Critically, 65.3% of all reported fraud incidents in 2024 involved digital banking channels. This is not a temporary spike. Banking apps alone bore the brunt of fraud, suffering losses exceeding R1.2 billion and accounting for 65% of digital fraud cases.

The overall picture is sobering: total financial crime losses, while dropping from R3.3 billion in 2023 to R2.7 billion in 2024, mask the explosion in digital and application fraud. SABRIC warns that fraud syndicates are becoming increasingly sophisticated, technologically advanced, and harder to detect, setting the stage for what experts describe as a potential “fraud storm” in 2025.

5.2 Beyond Digital: The Application Fraud Crisis

Digital banking fraud represents only one dimension of the crisis. Application fraud has become another major growth area that threatens bank profitability and balance sheet quality.

Vehicle Asset Finance (VAF) fraud surged by almost 50% in 2024, with potential losses estimated at R23 billion. This is not primarily digital fraud; it involves sophisticated document forgery, cloned vehicles, synthetic identities, and increasingly, AI generated employment records and payslips to deceive financing systems.

Unsecured credit fraud rose sharply by 57.6%, with more than 62,000 fraudulent applications reported. Actual losses more than doubled from the previous year to R221.7 million, demonstrating that approval rates for fraudulent applications are improving from the criminals’ perspective.

Home loan fraud, though slightly down in reported case numbers, remains highly lucrative for organized crime. Fraudsters are deploying AI modified payslips, deepfake video calls for identity verification, and sophisticated impersonation techniques to secure financing that will never be repaid.

5.3 The AI Powered Evolution of Fraud Techniques

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence has fundamentally changed the fraud landscape. According to SABRIC CEO Andre Wentzel, criminals are leveraging AI to create scams that appear more legitimate and convincing than ever before.

From error free phishing emails to AI generated WhatsApp messages that perfectly mimic a bank’s communication style, and even voice cloned deepfakes impersonating bank officials or family members, these tactics highlight an unsettling reality: the traditional signals that helped clients identify fraud are disappearing.

SABRIC has cautioned that in 2025, real time deepfake audio and video may become common tools in fraud schemes. Early cases have already emerged of fraudsters using AI voice cloning to impersonate individuals and banking officials with chilling accuracy.

Importantly, SABRIC emphasizes that these incidents result from social engineering techniques that exploit human error rather than technical compromises of banking platforms. No amount of technical security investment alone can solve a problem that fundamentally targets human psychology and decision making under pressure.

5.3.1 The Android Malware Explosion: Repackaging and Overlay Attacks

Beyond AI powered social engineering, South African banking clients face a sophisticated Android malware ecosystem that operates largely undetected until accounts are drained.

Repackaged Banking Apps: Criminals are downloading legitimate banking apps from official stores, decompiling them, injecting malicious code, and repackaging them for distribution through third party app stores, phishing links, and even legitimate looking websites. These repackaged apps function identically to the real banking app, making detection nearly impossible for most users. Once installed, they silently harvest credentials, intercept one time passwords, and grant attackers remote control over the device.

GoldDigger and Advanced Banking Trojans: The GoldDigger banking trojan, first identified targeting South African and Vietnamese banks, represents the evolution of mobile banking malware. Unlike simple credential stealers, GoldDigger uses multiple sophisticated techniques: it abuses Android accessibility services to read screen content and interact with legitimate banking apps, captures biometric authentication attempts, intercepts SMS messages containing OTPs, and records screen activity to capture PINs and passwords as they are entered. What makes GoldDigger particularly dangerous is its ability to remain dormant for extended periods, activating only when specific banking apps are launched to avoid detection by antivirus software.

Overlay Attacks: Overlay attacks represent perhaps the most insidious form of Android banking malware. When a user opens their legitimate banking app, the malware detects this and instantly displays a pixel perfect fake login screen overlaid on top of the real app. The user, believing they are interacting with their actual banking app, enters credentials directly into the attacker’s interface. Modern overlay attacks are nearly impossible for average users to detect. The fake screens match the bank’s branding exactly, include the same security messages, and even replicate loading animations. By the time the user realizes something is wrong, usually when money disappears, the malware has already transmitted credentials and initiated fraudulent transactions.

The Scale of the Android Threat: Unlike iOS devices which benefit from Apple’s strict app ecosystem controls, Android’s open architecture and South Africa’s high Android market share create a perfect storm for mobile banking fraud. Users sideload apps from untrusted sources, delay security updates due to data costs, and often run older Android versions with known vulnerabilities. It’s important to note that the various Android variants hold roughly 70–73% of the global mobile operating system market share as of late 2025. In South Africa, Android holds a slightly higher share of 81–82 % of mobile devices.

For banks, this creates an impossible support burden. When a client’s account is compromised through malware they installed themselves, who bears responsibility? Under emerging fraud liability frameworks like the UK’s 50:50 model, banks may find themselves reimbursing losses even when the client unknowingly installed malware, creating enormous financial exposure with no clear technical solution.

The only effective defence is a combination of server side behavioural analysis to detect anomalous login patterns, device fingerprinting to identify compromised devices, and aggressive client education; but even this assumes clients will recognize and act on warnings, which social engineering attacks have proven they often will not.

5.4 The Operational and Reputational Burden of Fraud

Every fraud incident triggers a cascade of costs that extend far beyond the direct financial loss. Banks must investigate each case, which requires specialized fraud investigation teams working around the clock. They must manage call centre volume spikes as concerned clients seek reassurance that their accounts remain secure. They must fulfill regulatory reporting obligations that have become increasingly stringent. They must absorb reputational damage that can persist for years and influence client acquisition costs.

Client trust, once broken by a poor fraud response, is nearly impossible to rebuild. In a market where clients maintain multiple banking relationships and can switch their primary account with minimal friction, a single high profile fraud failure can trigger mass attrition.

Complexity magnifies this operational burden in ways that are not immediately obvious. clients who do not fully understand their bank’s products, account structures, or transaction limits are slower to recognize abnormal activity. They are more susceptible to social engineering attacks that exploit confusion about how banking processes work. They are more likely to contact support for clarification, driving up operational costs even when no fraud has occurred.

In this way, confusing product structures do not merely frustrate clients. They actively increase both fraud exposure and the operational costs of managing fraud incidents. A bank with ten account types, each with subtly different fee structures and transaction limits, creates far more opportunities for confusion than one with a single, clearly defined offering.

5.5 The UK Model: Fraud Liability Sharing Between Banks

The United Kingdom has introduced a revolutionary approach to fraud liability that fundamentally changes the economics of payment fraud. Since October 2024, UK payment service providers have been required to split fraud reimbursement liability 50:50 between the sending bank (victim’s bank) and the receiving bank (where the fraudster’s account is held).

Under the Payment Systems Regulator’s mandatory reimbursement rules, UK PSPs must reimburse in scope clients up to £85,000 for Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud, with costs shared equally between sending and receiving firms. The sending bank must reimburse the victim within five business days of a claim being reported, or within 35 days if additional investigation time is required.

This represents a fundamental shift from the previous voluntary system, which placed reimbursement burden almost entirely on the sending bank and resulted in highly inconsistent outcomes. In 2022, only 59% of APP fraud losses were returned to victims under the voluntary framework. The new mandatory system ensures victims are reimbursed in most cases, unless the bank can prove the client acted fraudulently or with gross negligence.

The 50:50 split creates powerful incentives that did not exist under the old model. Receiving banks, which previously had little financial incentive to prevent fraudulent accounts from being opened or to act quickly when suspicious funds arrived, now bear direct financial liability. This has driven unprecedented collaboration between sending and receiving banks to detect fraudulent behavior, interrupt mule account activities, and share intelligence about emerging fraud patterns.

Sending banks are incentivized to implement robust fraud warnings, enhance real time transaction monitoring, and educate clients about common scam techniques. Receiving banks must tighten account opening procedures, monitor for suspicious deposit patterns, and act swiftly to freeze accounts when fraud is reported.

5.6 When South Africa Adopts Similar Regulations: The Coming Shock

When similar mandatory reimbursement and liability sharing regulations are eventually applied in South Africa, and they almost certainly will be, the operational impact will be devastating for banks operating at the margins.

The economics are straightforward and unforgiving. Banks with weak fraud detection capabilities, limited balance sheets to absorb reimbursement costs, or fragmented operations spanning multiple systems will face an impossible choice: invest heavily and immediately in fraud prevention infrastructure, or accept unsustainable losses from mandatory reimbursement obligations.

For smaller challenger banks, retailer or telco backed banks without deep fraud expertise, and any bank that has prioritized client acquisition over operational excellence, this regulatory shift could prove existential. The UK experience provides a clear warning: smaller payment service providers and start up financial services companies have found it prohibitively costly to comply with the new rules. Some have exited the market entirely. Others have been forced into mergers or partnerships with larger institutions that can absorb the compliance and reimbursement costs.

Consider the mathematics for a sub scale bank in South Africa. If digital fraud continues growing at 86% annually and mandatory 50:50 reimbursement is introduced, a bank with 500,000 active accounts could face tens of millions of rand in annual reimbursement costs before any investment in prevention systems. For a bank operating on thin margins with limited capital reserves, this is simply not sustainable.

The banks that will survive this transition are those that can achieve the scale necessary to amortize fraud prevention costs across millions of active relationships. Fraud detection systems, AI powered transaction monitoring, specialized investigation teams, and rapid response infrastructure all require significant fixed investment. These costs do not scale linearly with client count; they are largely fixed regardless of whether a bank serves 100,000 or 10 million clients.

Banks that cannot achieve this scale will find themselves in a death spiral where fraud losses and reimbursement obligations consume an ever larger percentage of revenue, forcing them to cut costs in ways that further weaken fraud prevention, creating even more losses. This dynamic will accelerate the consolidation that is already inevitable for other reasons.

The pressure will be particularly acute for banks that positioned themselves as low friction, high speed account opening experiences. Easy onboarding is a client experience win, but it is also a fraud liability nightmare. Under mandatory reimbursement with shared liability, banks will be forced to choose between maintaining fast onboarding and accepting massive fraud costs, or implementing stricter controls that destroy the very speed that differentiated them.

The only viable path forward for most banks will be radical simplification of products to reduce client confusion, massive investment in AI powered fraud detection, and either achieving scale through growth or accepting acquisition by a larger institution. The banks hustling at the margins, offering mediocre fraud prevention while burning cash on client acquisition, will not survive the transition to mandatory reimbursement.

If a bank gets fraud wrong, no amount of free banking, innovative features, or marketing spend will save it. Trust and safety will become the primary differentiators in South African banking, and the banks that invested early and deeply in fraud prevention will capture a disproportionate share of the primary account relationships that actually matter.

6.0 Technology as a Tailwind and a Trap for New Banks

Technology has dramatically lowered the barrier to starting a bank. Cloud infrastructure, software based cores, and banking platforms delivered as services mean a regulated banking operation can now be launched in months rather than years. This is a genuine tailwind and it will embolden more companies to attempt banking.

Retailers, insurers, fintechs, and digital platforms increasingly believe that with the right vendor stack they can become banks.

That belief is only partially correct.

6.1 Bank in a Box and SaaS Banking

Modern platforms promise fast launches and reduced engineering effort by packaging accounts, payments, cards, and basic lending into ready made systems.

Common examples include Mambu, Thought Machine, Temenos cloud deployments, and Finacle, alongside banking as a service providers such as Solaris, Marqeta, Stripe Treasury, Unit, Vodeno, and Adyen Issuing.

These platforms dramatically reduce the effort required to build a core banking system. What once required years of bespoke engineering can now be achieved in a fraction of the time.

But this is where many new entrants misunderstand the problem.

6.2 The Core Is a Small Part of Running a Bank

The core banking system is no longer the hard part. It is only a small fraction of the total effort and overhead of running a bank.

The real complexity sits elsewhere:

• Fraud prevention and reimbursement

• Credit risk and underwriting

• Financial crime operations

• Regulatory reporting and audit

• Customer support and dispute handling

• Capital and liquidity management

• Governance and accountability

A bank in a box provides undifferentiated infrastructure. It does not provide a sustainable banking business.

6.3 Undifferentiated Technology, Concentrated Risk

Modern banking platforms are intentionally generic. New banks often start with the same capabilities, the same vendors, and similar architectures.

As a result:

• Technology is rarely a lasting differentiator

• Customer experience advantages are quickly copied

• Operational weaknesses scale rapidly through digital channels

What appears to be leverage can quickly become fragility if not matched with deep operational competence and scaling out quickly, meaningfully to millions of clients. Banking is not a “hello world” moment, my first banking app has to come with significant and meaningful differences then scale quickly.

6.4 Why This Accelerates Consolidation

Technology makes it easier to start a bank but harder to sustain one.

It encourages more entrants, but ensures that many operate similar utilities with little durable differentiation. Those without discipline in cost control, risk management, and execution become natural consolidation candidates.

In a world where the core is commoditised, banking success is determined by operational excellence, the scale of the ecosystem clients interact with and not software selection.

Technology has made starting a bank easier, but it has not made running one simpler.

7. The Reality of Multi Banking and Dormant Accounts

South Africans are no longer loyal to a single bank. The abundance of options and the proliferation of zero fee accounts has fundamentally changed consumer behavior. Most consumers now maintain a salary account, a zero fee transactional account, a savings pocket somewhere else, and possibly a retailer or telco wallet.

This shift has created an ecosystem characterized by millions of dormant accounts, high acquisition but low engagement economics, and marketing vanity metrics that mask unprofitable user bases. Banks celebrate account openings while ignoring that most of these accounts will never become active, revenue generating relationships.

7.1 The Primary Account Remains King

Critically, salaries still get paid into one primary account. That account, the financial home, is where long term value accrues. It receives the monthly inflow, handles the bulk of payments, and becomes the anchor of the client’s financial life. Secondary accounts are used opportunistically for specific benefits, but they rarely capture the full relationship.

The battle for primary account status is therefore the only battle that truly matters. Everything else is peripheral.

8. The Coming Consolidation: Not Everyone Survives Abundance

There is a persistent fantasy in financial services that the current landscape can be preserved with enough innovation, enough branding, or enough regulatory patience. It cannot.

Abundance collapses margins, exposes fixed costs, and strips away the illusion of differentiation. The system does not converge slowly. It snaps. The only open question is whether institutions choose their end state, or have it chosen for them.

8.1 The Inevitable End States

Despite endless strategic options being debated in boardrooms, abundance only allows for a small number of viable outcomes.

End State 1: Primary Relationship Banks (Very Few Winners). A small number of institutions become default financial gravity wells. They hold the client’s salary and primary balance. They process the majority of transactions. They anchor identity, trust, and data consent. Everyone else integrates around them. These banks win not by having the most features, but by being operationally boring, radically simple, and cheap at scale. In South Africa, this number is likely two, maybe three. Not five. Not eight. Everyone else who imagines they will be a primary bank without already behaving like one is delusional.

End State 2: Platform Banks That Own the Balance Sheet but Not the Brand. These institutions quietly accept reality. They own compliance, capital, and risk. They power multiple consumer facing brands. They monetize through volume and embedded finance. Retailers, telcos, and fintechs ride on top. The bank becomes infrastructure. This is not a consolation prize. It is seeing the board clearly. But it requires executives to accept that brand ego is optional. Most will fail this test.

End State 3: Feature Banks and Specialist Utilities. Some institutions survive by narrowing aggressively. They become lending specialists, transaction processors, or foreign exchange and payments utilities. They stop pretending to be universal banks. They kill breadth to preserve depth. This path is viable, but brutal. It requires shrinking the organisation, killing products, and letting clients go. Few management teams have the courage to execute this cleanly.

End State 4: Zombie Institutions (The Most Common Outcome). This is where most end up. Zombie banks are legally alive. They have millions of accounts. They are nobody’s primary relationship. They bleed slowly through dormant clients, rising unit costs, and talent attrition. Eventually they are sold for parts, merged under duress, or quietly wound down. This is not stability. It is deferred death.

8.2 The Lie of Multi Banking Forever

Executives often comfort themselves with the idea that clients will happily juggle eight banks, twelve apps, and constant money movement. This is nonsense.

clients consolidate attention long before they consolidate accounts. The moment an institution is no longer default, it is already irrelevant. Multi banking is a transition phase, not an end state.

8.3 Why Consolidation Will Hurt More Than Expected

Consolidation is painful because it destroys illusions: that brand loyalty was real, that size implied relevance, that optionality was strategy.

It exposes overstaffed middle layers, redundant technology estates, and products that never should have existed. The pain is not just financial. It is reputational and existential.

8.4 The Real Divide: Those Who Accept Gravity and Those Who Deny It

Abundance creates gravity. clients, data, and liquidity concentrate.

Institutions that accept this move early, choose roles intentionally, and design for integration. Those that resist it protect legacy, multiply complexity, and delay simplification. And then they are consolidated without consent.

9. The Traits That Will Cause Institutions to Struggle

Abundance does not reward everyone equally. In fact, it is often brutal to incumbents and late movers because it exposes structural weakness faster than scarcity ever did. As transaction costs collapse, margins compress, and clients gain unprecedented choice, certain organisational traits become existential liabilities.

9.1 Confusing Complexity with Control

Many struggling institutions believe that complexity equals safety. Over time they accumulate multiple overlapping products solving the same problem, redundant approval layers, duplicated technology platforms, and slightly different pricing rules for similar clients.

This complexity feels like control internally, but externally it creates friction, confusion, and cost. In an abundant world, clients simply route around complexity. They do not complain, they do not escalate, they just leave.

Corporate culture symptom: Committees spend three months debating whether a new savings account should have 2.5% or 2.75% interest while competitors launch entire banks.

Abundance rewards clarity, not optionality.

9.2 Optimising for Internal Governance Instead of client Outcomes

Organisations that struggle tend to design systems around committee structures, reporting lines, risk ownership diagrams, and policy enforcement rather than client experience.

The result is products that are technically compliant but emotionally hollow. When zero cost competitors exist, clients gravitate toward institutions that feel intentional, not ones that feel procedurally correct.

Corporate culture symptom: Product launches require sign off from seventeen people across eight departments, none of whom actually talk to clients.

Strong governance matters, but when governance becomes the product, clients disengage.

9.3 Treating Technology as a Project Instead of a Capability

Struggling companies still think in terms of “the cloud programme”, “the core replacement project”, or “the digital transformation initiative”.

These organisations fund technology in bursts, pause between efforts, and declare victory far too early. In contrast, winners treat technology as a permanent operating capability, continuously refined and quietly improved.

Corporate culture symptom: CIOs present three year roadmaps in PowerPoint while engineering teams at winning banks ship code daily.

Abundance punishes stop start execution. The market does not wait for your next funding cycle.

9.4 Assuming clients Will Act Rationally

Many institutions believe clients will naturally rationalise their financial lives: “They’ll close unused accounts eventually”, “They’ll move everything once they see the benefits”, “They’ll optimise for fees and interest rates”.

In reality, clients are lazy optimisers. They consolidate only when there is a clear emotional or experiential pull, not when spreadsheets say they should.

Corporate culture symptom: Marketing teams celebrate 2 million account openings while finance quietly notes that 1.8 million are dormant and generating losses.

Companies that rely on rational client behaviour end up with large numbers of dormant, loss making relationships and very few primary ones.

9.5 Designing Products That Require Perfect Behaviour

Another common failure mode is designing offerings that only work if clients behave flawlessly: repayments that must happen on rigid schedules, penalties that escalate quickly, and products that assume steady income and stable employment.

In an abundant system, flexibility beats precision. Institutions that cannot tolerate variance, missed steps, or irregular usage push clients away, often toward simpler, more forgiving alternatives.

Corporate culture symptom: Credit teams reject 80% of applicants to hit target default rates, then express surprise when growth stalls.

The winners design for how people actually live, not how risk models wish they did.

9.6 Mistaking Distribution for Differentiation

Some companies believe scale alone will save them: large branch networks, massive client bases, and deep historical brand recognition.

But abundance erodes the advantage of distribution. If everyone can reach everyone digitally, then distribution without differentiation becomes a cost centre.

Corporate culture symptom: Executives tout “our 900 branches” as a competitive advantage while clients increasingly view them as an inconvenience.

Struggling firms often have reach, but no compelling reason for clients to engage more deeply or more often.

9.7 Fragmented Ownership and Too Many Decision Makers

When accountability is diffuse, every domain has its own technology head, no one owns end to end client journeys, and decisions are endlessly deferred across forums.

Execution slows to a crawl. Abundance favours organisations that can make clear, fast, and sometimes uncomfortable decisions.

Corporate culture symptom: Six different “digital transformation” initiatives run in parallel, each with its own budget, none talking to each other.

If everyone is in charge, no one is.

9.8 Protecting Legacy Revenue at the Expense of Future Relevance

Finally, struggling organisations are often trapped by their own success. They hesitate to simplify, reduce fees, or remove friction because it threatens existing revenue streams.

But abundance ensures that someone else will do it instead.

Corporate culture symptom: Finance vetoes removing a R5 monthly fee that generates R50 million annually, ignoring that it costs R200 million in client attrition and support calls.

Protecting yesterday’s margins at the cost of tomorrow’s relevance is not conservatism. It is delayed decline.

9.9 The Uncomfortable Truth

Abundance does not kill companies directly. It exposes indecision, over engineering, cultural inertia, teams working slavishly towards narrow anti-client KPIs and misaligned incentives.

The institutions that struggle are not usually the least intelligent or the least resourced. They are the ones most attached to how things used to work.

In an abundant world, simplicity is not naive. It is strategic.

10. The Traits That Enable Survival and Dominance

In stark contrast to the failing patterns above, the banks that will dominate South African banking over the next decade share a remarkably consistent set of traits.

10.1 Radically Simple Product Design

Winning banks offer one account, one card, one fee model, and one app. They resist the urge to create seventeen variants of the same product.

Corporate culture marker: Product managers can explain the entire product line in under two minutes without charts.

Complexity is a choice, and choosing simplicity requires discipline that most organisations lack.

10.2 Obsessive Cost Discipline Without Sacrificing Quality

Winners run aggressively low cost bases through modern cores, minimal branch infrastructure, and automation first operations. But they invest heavily where it matters: fraud prevention, client support when things go wrong, and system reliability.

Corporate culture marker: CFOs are revered, not resented. Every rand is questioned, but client impacting investments move fast.

Cheap does not mean shoddy. It means ruthlessly eliminating waste.

10.3 Treating Fraud as Warfare, Not Compliance

Dominant banks understand fraud is a permanent conflict requiring specialist teams, AI powered detection, real time monitoring, and rapid response infrastructure.

Corporate culture marker: Fraud teams have authority to freeze accounts, block transactions, and shut down attack vectors immediately. If you get fraud wrong, nothing else matters.

10.4 Speed Over Consensus

Winning organisations make fast decisions with incomplete information and course correct quickly. They ship features weekly, not quarterly.

Corporate culture marker: Teams use “disagree and commit” rather than “let’s form a working group to explore this further”.

Abundance punishes deliberation. The cost of being wrong is lower than the cost of being slow.

10.5 Designing for Actual Human Behaviour

Winners build products that work for how people actually live: irregular income, forgotten passwords, missed payments, confusion under pressure.

Corporate culture marker: Product teams spend time in call centres listening to why clients struggle, not in conference rooms hypothesising about ideal user journeys.

The best products feel obvious because they assume nothing about client behaviour except that it will be messy.

10.6 Becoming the Primary Account by Earning Trust in Crisis

The ultimate trait that separates winners from losers is this: winners are there when clients need them most. When fraud happens, when money disappears, when identity is stolen, they respond immediately with empathy and solutions.

Corporate culture marker: client support teams have real authority to solve problems on the spot, not scripts requiring three escalations to do anything meaningful.

Trust cannot be marketed. It must be earned in the moments that matter most.

11. The Consolidation Reality: How South African Banking Reorganises Itself

South African banking has moved beyond discussion to inevitability. The paradox in the market, abundant options but shrinking economics, is not a transitional phase; it is the structural condition driving consolidation. The forces shaping this are already visible: shrinking margins, collapsing transactional fees, exploding fraud costs, and clients fragmenting their banking relationships while never truly committing as primaries.

Consolidation is not a risk. It is the outcome.

11.1 The Economics That Drive Consolidation

The system that once rewarded scale and complexity now penalises them. Legacy governance, hybrid branch networks, dual technology stacks, and product breadth are all costs that cannot be supported when transactional revenue trends toward zero. Compliance, fraud prevention, cyber risk, KYC/AML, and ongoing supervision from SARB are fixed costs that do not scale with account openings.

clients are not spreading their value evenly across institutions; they are fragmenting activity but consolidating value into a primary account, the salary account, the balance that matters, the financial home. Others become secondary or dormant accounts with little commercial value.

This structural squeeze cannot be reversed by better branding, faster apps, or more channels. There is only one way out: simplify, streamline, or exit.

11.2 What Every Bank Must Do to Survive

Survival will not be granted by persistence or marketing. It will be earned by fundamentally changing the business model.

Radically reduce governance and decision overhead. Layers of committees and approvals must be replaced by automated controls and empowered teams. Slow decision cycles are death in a world where client behaviour shifts in days, not years.

Drastically cut cost to serve. Branch networks, legacy platforms, duplicated services, these are liabilities. Banks must automate operations, reduce support functions, and shrink cost structures to match the new economics.

Simplify and consolidate products. clients don’t value fifteen savings products, four transactional tiers, and seven rewards models. They want clarity, predictability, and alignment with their financial lives.

Modernise technology stacks. Old cores wrapped with new interfaces are stopgaps, not solutions. Banks must adopt modular, API first systems that cut marginal costs, reduce risk, and improve reliability.

Reframe fees to reflect value. clients expect free basic services. Fees will survive only where value is clear, credit, trust, convenience, and outcomes, not transactions.

Prioritise fraud and risk capability. Fraud is not a peripheral cost; it is a core determinant of economics. Banks must invest in real time detection, AI assisted risk models, and client education, or face disproportionate losses.

Focus on primary relationships. A bank that is never a client’s financial home will eventually become irrelevant.

11.3 Understanding Bank Tiers: What Separates Tier 1 from Tier 2

Not all traditional banks are equally positioned to survive consolidation. The distinction between Tier 1 and Tier 2 traditional banks is not primarily about size or brand heritage. It is about structural readiness for the economics of abundance.

Tier 1 Traditional Banks are characterised by demonstrated digital execution capability, with modern(ish) technology stacks either deployed or credibly in progress. They have diversified revenue streams that reduce dependence on transactional fees, including strong positions in corporate banking, investment banking, or wealth management. Their cost structures, while still high, show evidence of active rationalisation. Most critically, they have proven ability to ship digital products at competitive speed and have successfully defended or grown primary account relationships in the mass market.

Tier 2 Traditional Banks remain more dependent on legacy infrastructure and have struggled to modernise core systems at pace. Their revenue mix is more exposed to transactional fee compression, and cost reduction efforts have often stalled in governance complexity. Technology execution tends to be slower, more project based, and more prone to delays. They rely heavily on consultants to tell them what to do and have a sprawling array of vendor products that are poorly integrated. Primary account share in the mass market has eroded more significantly, leaving them more reliant on existing relationship inertia than active client acquisition.

The distinction matters because Tier 1 banks have a viable path to competing directly for primary relationships in the new economics. Tier 2 banks face harder choices: accelerate transformation dramatically, accept a platform or specialist role, or risk becoming acquisition targets or zombie institutions.

11.4 Consolidation Readiness by Category

Below is a high level summary of institutional categories and what they must do to survive:

| Category | What Must Change | Effort Required |

| Tier 1 Traditional Banks | Consolidate product stacks, automate risk and operations, maintain digital execution pace | High |

| Tier 2 Traditional Banks | Simplify governance, modernise core systems, drastically reduce costs, consider partnerships | Very High |

| Digital First Banks | Defend simplicity, scale risk and fraud capability, deepen primary engagement | Medium |

| Digital Challengers | Deepen primary engagement, invest heavily in fraud and lending capability, improve unit economics | Very High |

| Insurer Led Banks | Focus on profitable niches, leverage ecosystem integration, accept extended timeline to profitability | High |

| Specialist Lenders | Narrow focus aggressively, partner for distribution and technology, automate operations | Medium-High |

| Niche and SME Banks | Stay niche, automate aggressively, consider merger or specialisation | High |

| Sub Scale Banks | Partner or merge to gain scale, exit non-core activities | Very High |

| Mutual Banks | Simplify or consolidate early, consider cooperative mergers | Very High |

| Foreign Bank Branches | Shrink retail footprint, focus on corporate and institutional services | Medium |

This readiness spectrum illustrates the real truth: institutions with scale, execution discipline, and structural simplicity have the best odds; those without these characteristics will be absorbed or eliminated.

11.5 The Pattern of Consolidation

Consolidation will not be uniform. The most likely sequence is:

First, sub scale and mutual banks exit or merge. They are unable to amortise fixed costs across enough primary relationships.

Second, digital challengers face the choice: invest heavily or be acquired. Rapid client acquisition without deep engagement or lending depth is not sustainable in an environment where fraud liability looms large and fee income is near zero.

Third, traditional banks consolidate capabilities, not brands. Large banks will more often absorb technology, licences, and teams than merge brand to brand. Duplication will be eliminated inside existing platforms.

Fourth, foreign banks retreat to niches. Global players will prioritise corporate and institutional services, not mass retail banking, in markets where local economics are unfavourable.

11.6 Winners and Losers

Likely Winners: Digital first banks with proven simplicity and low cost models. Tier 1 traditional banks with strong digital execution. Any institution that genuinely removes complexity rather than just managing it.

Likely Losers: Sub scale challengers without lending depth. Institutions that equate governance with safety. Banks that fail to dramatically cut cost and complexity. Any organisation that protects legacy revenue at the expense of future relevance.

12. Back to the Future

Banking has become the new corporate fidget spinner, grabbing the attention of relevance staved corporates. Most don’t know why they want it, exactly what it is, but they know others have it and so it should be on the plan somewhere.

South African banking is no longer about who can build the most features or launch the most products. It is about cost discipline, trust under pressure, relentless simplicity, and scale that compounds rather than collapses.

The winners will not be the loudest innovators. They will be the quiet operators who make banking feel invisible, safe, and boring.

And in banking, boring done well is very hard to beat.

The consolidation outcome is not exotic. It is a return to a familiar pattern: a small number of dominant banks. We will likely end up back to the future, with a small number of dominant banks, which is exactly where we started.

The difference will be profound. Those dominant banks will be more client centric, with lower fees, lower fraud, better lending, and better, simpler client experiences.

The journey through abundance, with its explosion of choice, its vanity metrics of account openings, and its billions burned on client acquisition, will have served its purpose. It will have forced the industry to strip away complexity, invest in what actually matters, and compete on the only dimensions that clients genuinely value: trust, simplicity, and being there when things go wrong.

The market will consolidate not because regulators force it, but because economics demands it. South African banking is not being preserved. It is being reformed, by clients, by economics, and by the unavoidable logic of abundance.

Those who embrace the logic early will shape the future. Those who do not will watch it happen to them.

And when the dust settles, South African consumers will be better served by fewer, stronger institutions than they ever were by the fragmented abundance that preceded them.

12.1 Final Thought: The Danger of Fighting on Two Fronts

There is a deeper lesson embedded in the struggles of crossover players that pour energy and resources into secondary, loss-making businesses typically do so by redirecting investment and operational focus from their primary business. This redirection is rarely neutral. It weakens the core.

Every rand allocated to the second front, every executive hour spent in strategy sessions, every technology resource committed to banking infrastructure is a rand, an hour, and a resource that cannot be deployed to defend and strengthen the primary businesses that actually generate profit today.

Growth into secondary businesses must be evaluated not just on their own merits, but in terms of how dominant and successful the company has been in its primary business. If you are not unquestionably dominant in your core market, if your primary business still faces existential competitive threats, if you have not achieved such overwhelming scale and efficiency that your position is effectively unassailable, then opening a second front is strategic suicide.

It is like opening another front in a war when the first front is not secured. You redirect troops, you split command attention, you divide logistics, and you leave your current positions weakened and vulnerable to counterattack. Your competitors in the primary business do not pause while you build the secondary one. They exploit the distraction.

Banks that will thrive are those that have already won their primary battle so decisively that expansion becomes an overflow of strength rather than a diversion of it. Capitec can expand into mobile networks because they have already dominated transactional banking. They are not splitting focus; they are leveraging surplus capacity.

Institutions that have not yet won their core market, that are still fighting for primary account relationships, that have not yet achieved the operational excellence and cost discipline required to survive in abundance, cannot afford the luxury of secondary ambitions.

The market will punish divided attention ruthlessly. And in South African banking, where fraud costs are exploding, margins are collapsing, and consolidation is inevitable, there is no forgiveness for strategic distraction.

The winners will be those who understood that dominance in one thing beats mediocrity in many. And they will inherit the market share of those who learned that lesson too late.

13. Authors Note

This article synthesises public data, regulatory reports, industry analysis, and observed market behaviour. Conclusions are forward-looking and represent the author’s interpretation of structural trends rather than predictions of specific outcomes. The author is sharing opinion and is in now way claiming to have any special insights or be an expert in predicting the future.

14. Sources

- Wikipedia — List of banks in South Africa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_banks_in_South_Africa

(Structure of the South African banking system) - PwC South Africa — Major Banks Analysis

https://www.pwc.co.za/en/publications/major-banks-analysis.html

(Performance, digital transformation, and competitive dynamics of major banks) - South African Reserve Bank (SARB) — Banking Sector Risk Assessment Report

https://www.resbank.co.za/content/dam/sarb/publications/media-releases/2022/pa-assessment-reports/Banking%20Sector%20Risk%20Assessment%20Report.pdf

(Systemic risks including fraud and compliance costs) - Banking Association of South Africa / SABRIC — Financial Crime and Fraud Statistics

https://www.banking.org.za/news/sabric-reports-significant-increase-in-financial-crime-losses-for-2023/

(Industry-wide fraud trends) - Reuters — South Africa’s Nedbank annual profit rises on non-interest revenue growth

https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/south-africas-nedbank-full-year-profit-up-non-interest-revenue-growth-2025-03-04/

(Recent financial performance) - Reuters — Nedbank sells 21.2% Ecobank stake

https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nedbank-sells-100-million-ecobank-stake-financier-nkontchous-bosquet-investments-2025-08-15/

(Strategic refocus and portfolio rationalisation) - Nedbank Group (official) — About Us & Strategy Overview

https://group.nedbank.co.za/home/about-us.html

(Strategy including digital leadership and cost-income focus) - Nedbank Group (official) — Managed Evolution digital transformation

https://group.nedbank.co.za/news-and-insights/press/2024/euromoney-2024-awards.html

(Euromoney 2024 Awards) - Nedbank CFO on Digital Transformation (CFO South Africa)

https://cfo.co.za/articles/digital-transformation-is-not-optional-says-nedbank-cfo-mike-davis/

(Executive perspective on digital transformation) - Nedbank Interim / Annual Financial Results (official)

https://group.nedbank.co.za/news-and-insights/press/2025/nedbank-delivers-improved-financial-performance.html

(Interim and annual 2025/2024 financial performance) - Moneyweb — Did Old Mutual pick the exact wrong time to launch a bank?

https://www.moneyweb.co.za/news/companies-and-deals/did-old-mutual-pick-the-exact-wrong-time-to-launch-a-bank/

(Analysis of Old Mutual’s banking entry and competitive context) - Wikipedia — Old Mutual

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Mutual

(Background on the group launching a new bank) - Moneyweb — Old Mutual to open new SA bank in 2025

https://www.moneyweb.co.za/news/companies-and-deals/old-mutual-to-open-new-sa-bank-in-2025/

(Coverage of planned bank launch) - Old Mutual (official) — OM Bank CEO gets regulatory approval from SARB

https://www.oldmutual.co.za/news/om-bank-ceo-gets-the-thumbs-up-from-the-reserve-bank/

(Confirmation of launch timeline) - Zensar Technologies — South Africa Financial Services Outlook 2025

https://www.zensar.com/assets/files/3lMug4iZgOZE5bT35uh4YE/SA-Financial-Service-Trends-2025-WP-17_04_25.pdf

(Digital disruption, cost pressure, and technology trends) - BDO South Africa — Fintech in Africa Report 2024

https://www.bdo.co.za/getmedia/0a92fd54-18e6-4a18-8f21-c22b0ae82775/Fintech-in-Africa-Report-2024_June.pdf

(Broader fintech impact) - Hippo.co.za — South African banking fees comparison

https://www.hippo.co.za/money/banking-fees-guide/

(Competitive fee pressure) - Wikipedia — Discovery Bank

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discovery_Bank

(Context on another digital bank) - Wikipedia — TymeBank

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TymeBank

(Digital bank competitor in South Africa) - Wikipedia — Bank Zero

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_Zero

(Digital mutual bank in South Africa) - Banking CX from Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/capitec-wins-absa-standard-bank-confuse-lessons-product-ndebele-oc1pf?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios&utm_campaign=share_via

- Global Android Market Share (Mobile OS) https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/worldwide (StatCounter Global Stats)

Thought-provoking and well articulated. A pragmatic take on abundance, margin pressure, and why consolidation in South African banking feels inevitable. The emphasis on primary relationships and fraud economics is especially relevant.

Interesting discussion points for some holiday season reflection. Some thoughts while reading:

– Is there really a big gap in data availability for retailers who already have successful loyalty programs – it seems like they should have much of the supplier negotiating power suggested? The bank picture would give share of wallet and perhaps competitor insights – but some might be getting that data from their acquirer or payfac – albeit in anonymized format. There are also other other privacy protected insight approaches to getting some of these insights.

– On fee compression (and also payment acceptance costs for retailers) it would be good to hear your thoughts in future on the acquiring and payment facilitation space and future margin compression there. Many banks globally are in two minds whether to be in the facilitation business or not. With the Capitec acquisition of the modest sized Walletdoc coupled with Mercantile’s acquiring presence perhaps there are future plans for competitive offers in the local market?

– Regarding the entrance of Old Mutual: It feels like they already tested the waters this time round as they grew their unsecured lending book and also pursued the Bidvest partnership. It could also be that there is a defensive as well as offensive play in that there may be distinct benefits from transactional insights when it comes to selling policies – especially in a market with lots of gig style workers and high policy sale / issue costs to recover and Capitec now competing. Not sure certain on the exec departures but I seem to recall it might have been planned from the start that they would just be in role just for the build phase. From a regulatory perspective I think you perhaps underestimate the overlap – KYC, dispute resolution, fraud (in different formats – but certainly including first party fraud), balance sheet reporting etc. are similar. It does seem strange that it is so expensive to enter the SA market though – in other comparable markets it has been possible to get neobanks up and running for under $100M.

– Agree with the many interesting points on the fraud front – especially on the staggering levels of first party and vehicle fraud (partly boosted by weakened controls during COVID). The basic banking issues of account takeover on the other hand seem to be diminishing while scams increase by duping customers directly in the account-to-account payment space (APP fraud) and sometimes by hijacking ecommerce merchants in the card space. Perhaps not so many of these are reimbursable by the bank today – so while the absolute values you mention sound high the relative impact may still not be that great. Certainly a lot of the red flags in the authorised push payment (APP) space are on the receiving account side. A split liability model like the ones you describe would seem to have value for customers and some banks. I’m aware that Capitec might already be pursuing some efforts around cross-bank intelligence for A2A fraud. Possibly the SARB will consider split liability for Payshap in the future. Successful implementation might gradually drive some card business to A2A due to the greater protections provided.

– Regarding the future end-state there’s a chance there might be some level of disruption as customers increasingly compare products and with AI and perhaps even appoint agents to manage some parts of their financial affairs (e.g. a risk agent, a PFM agent etc.). How much insight and memory might such agents benefit from relative to what the bank has today? I think it’s too early to say what the extent of the impact will be (if any) and whether it might favour incumbents or new entrants and full service vs. niche players.