1. Introduction

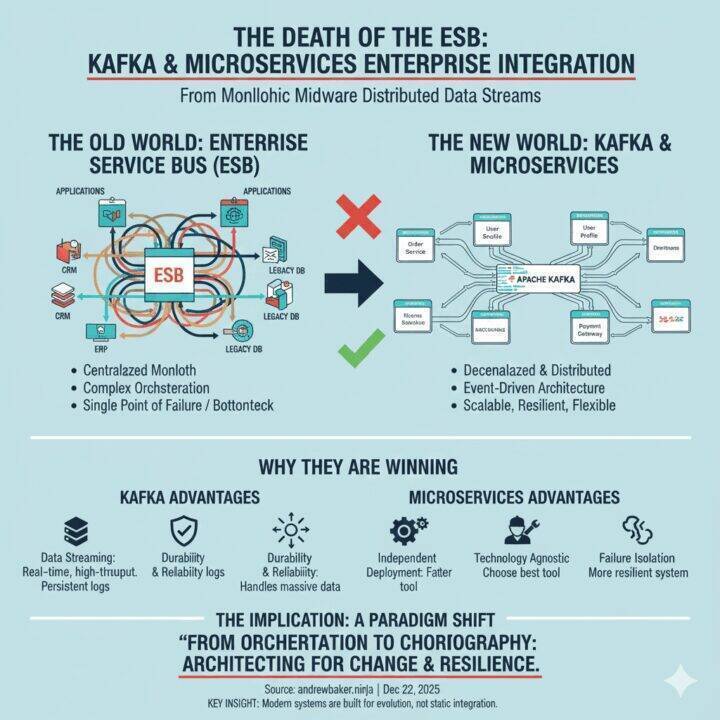

The Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) once promised to be the silver bullet for enterprise integration. Organizations invested millions in platforms like MuleSoft, IBM Integration Bus, Oracle Service Bus, and TIBCO BusinessWorks, believing they would solve all their integration challenges. Today, these same organizations are discovering that their ESB has become their biggest architectural liability.

The rise of Apache Kafka, Spring Boot, and microservices architecture represents more than just a technological shift. It represents a fundamental rethinking of how we build scalable, resilient systems. This article examines why ESBs are dying, how they actively harm businesses, and why the combination of Java, Spring, and Kafka provides a superior alternative.

2. The False Promise of the ESB

Enterprise Service Buses emerged in the early 2000s as a solution to point-to-point integration chaos. The pitch was compelling: a single, centralized platform that would mediate all communication between systems, apply transformations, enforce governance, and provide a unified integration layer.

The reality turned out very differently. What organizations got instead was a monolithic bottleneck that became increasingly difficult to change, scale, or maintain. The ESB became the very problem it was meant to solve.

3. How ESBs Kill Business Velocity

3.1. The Release Coordination Nightmare

Every change to an ESB requires coordination across multiple teams. Want to update an endpoint? You need to test every flow that might be affected. Need to add a new integration? You risk breaking existing integrations. The ESB becomes a coordination bottleneck where release cycles stretch from days to weeks or even months.

In a Kafka and microservices architecture, services are independently deployable. Teams can release changes to their own services without coordinating with dozens of other teams. A payment service can be updated without touching the order service, the inventory service, or any other component. This independence translates directly to business velocity.

3.2. The Scaling Ceiling

ESBs scale vertically, not horizontally. When you hit performance limits, you buy bigger hardware or cluster nodes, which introduces complexity and cost. More critically, you hit hard limits. There is only so much you can scale a monolithic integration platform.

Kafka was designed for horizontal scaling from day one. Need more throughput? Add more brokers. Need to handle more consumers? Add more consumer instances. A single Kafka cluster can handle millions of messages per second across hundreds of nodes. This is not theoretical scaling. This is proven at companies like LinkedIn, Netflix, and Uber handling trillions of events daily.

3.3. The Single Point of Failure Problem

An ESB is a single critical service that everything depends on. When it goes down, your entire business grinds to a halt. Payments stop processing. Orders cannot be placed. Customer requests fail. The blast radius of an ESB failure is catastrophic.

With Kafka and microservices, failure is isolated. If one microservice fails, it affects only that service’s functionality. Kafka itself is distributed and fault tolerant. With proper replication settings, you can lose entire brokers without losing data or availability. The architecture is resilient by design, not by hoping your single ESB cluster stays up.

4. The Technical Debt Trap

4.1. Upgrade Hell

ESB upgrades are terrifying events. You are upgrading a platform that mediates potentially hundreds of integrations. Testing requires validating every single flow. Rollback is complicated or impossible. Organizations commonly run ESB versions that are years out of date because the risk and effort of upgrading is too high.

Spring Boot applications follow standard semantic versioning and upgrade paths. Kafka upgrades are rolling upgrades with backward compatibility guarantees. You upgrade one service at a time, one broker at a time. The risk is contained. The effort is manageable.

4.2. Vendor Lock-In

ESB platforms come with proprietary development tools, proprietary languages, and proprietary deployment models. Your integration logic is written in vendor-specific formats that cannot be easily migrated. When you want to leave, you face rewriting everything from scratch.

Kafka is open source. Spring is open source. Java is a standard. Your code is portable. Your skills are transferable. You are not locked into a single vendor’s roadmap or pricing model.

4.3. The Talent Problem

Finding developers who want to work with ESB platforms is increasingly difficult. The best engineers want to work with modern technologies, not proprietary integration platforms. ESB skills are legacy skills. Kafka and Spring skills are in high demand.

This talent gap creates a vicious cycle. Your ESB becomes harder to maintain because you cannot hire good people to work on it. The people you do have become increasingly specialized in a dying technology, making it even harder to transition away.

5. The Pitfalls That Kill ESBs

5.1. Message Poisoning

A single malformed message can crash an ESB flow. Worse, that message can sit in a queue or topic, repeatedly crashing the flow every time it is processed. The ESB lacks sophisticated dead-letter queue handling, lacks proper message validation frameworks, and lacks the observability to quickly identify and fix poison message problems.

Kafka with Spring Kafka provides robust error handling. Dead-letter topics are first-class concepts. You can configure retry policies, error handlers, and message filtering at the consumer level. When poison messages occur, they are isolated and can be processed separately without bringing down your entire integration layer.

5.2. Resource Contention

All integrations share the same ESB resources. A poorly performing transformation or a high-volume integration can starve other integrations of CPU, memory, or thread pool resources. You cannot isolate workloads effectively.

Microservices run in isolated containers with dedicated resources. Kubernetes provides resource quotas, limits, and quality-of-service guarantees. One service consuming excessive resources does not impact others. You can scale services independently based on their specific needs.

5.3. Configuration Complexity

ESB configurations grow into sprawling XML files or proprietary configuration formats with thousands of lines. Understanding the full impact of a change requires expert knowledge of the entire configuration. Documentation falls out of date. Tribal knowledge becomes critical.

Spring Boot uses convention over configuration with sensible defaults. Kafka configuration is straightforward properties files. Infrastructure-as-code tools like Terraform and Helm manage deployment configurations in version-controlled, testable formats. Complexity is managed through modularity, not through ever-growing monolithic configurations.

5.4. Lack of Elasticity

ESBs cannot auto-scale based on load. You provision for peak capacity and waste resources during normal operation. When unexpected load hits, you cannot quickly add capacity. Manual intervention is required, and by the time you scale up, you have already experienced an outage.

Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler can scale microservices based on CPU, memory, or custom metrics like message lag. Kafka consumer groups automatically rebalance when you add or remove instances. The system adapts to load automatically, scaling up during peaks and scaling down during quiet periods.

6. The Java, Spring, and Kafka Alternative

6.1. Modern Java Performance

Java 25 represents the cutting edge of JVM performance and developer productivity. Virtual threads, now mature and production-hardened, enable massive concurrency with minimal resource overhead. The pauseless garbage collectors, ZGC and Shenandoah, eliminate GC pause times even for multi-terabyte heaps, making Java competitive with languages that traditionally claimed performance advantages.

The ahead-of-time compilation cache dramatically reduces startup times and improves peak performance by sharing optimized code across JVM instances. This makes Java microservices start in milliseconds rather than seconds, fundamentally changing deployment dynamics in containerized environments.

This is not incremental improvement. Java 25 represents a generational leap in performance, efficiency, and developer experience that makes it the ideal foundation for high-throughput microservices.

6.2. Spring Boot Productivity

Spring Boot eliminates boilerplate. Auto-configuration sets up your application with sensible defaults. Spring Kafka provides high-level abstractions over Kafka consumers and producers. Spring Cloud Stream enables event-driven microservices with minimal code.

A complete Kafka consumer microservice can be written in under 100 lines of code. Testing is straightforward with embedded Kafka. Observability comes built in with Micrometer metrics and distributed tracing support.

6.3. Kafka as the Integration Backbone

Kafka is not just a message broker. It is a distributed commit log that provides durable, ordered, replayable streams of events. This fundamentally changes how you think about integration.

With Kafka 4.2, the platform has evolved even further by introducing native queue support alongside its traditional topic-based architecture. This means you can now implement classic queue semantics with competing consumers for workload distribution while still benefiting from Kafka’s durability, scalability, and operational simplicity. Organizations no longer need separate queue infrastructure for point-to-point messaging patterns.

Instead of request-response patterns mediated by an ESB, you have event streams that services can consume at their own pace. Instead of transformations happening in a central layer, transformations happen in microservices close to the data. Instead of a single integration layer, you have a distributed data platform that handles both streaming and queuing workloads.

7. Real-World Patterns

7.1. Event Sourcing

Store every state change as an event in Kafka. Your services consume these events to build their own views of the data. You get complete audit trails, temporal queries, and the ability to rebuild state by replaying events.

ESBs cannot do this. They are designed for transient message passing, not durable event storage.

7.2. Change Data Capture

Use tools like Debezium to capture database changes and stream them to Kafka. Your microservices react to these change events without complex database triggers or polling. You get near real-time data pipelines without the fragility of ESB database adapters.

7.3. Saga Patterns

Implement distributed transactions using choreography or orchestration patterns with Kafka. Each service publishes events about its local transactions. Other services react to these events to complete their portion of the saga. You get eventual consistency without distributed locks or two-phase commit.

ESBs attempt to solve this with BPEL or proprietary orchestration engines that become unmaintainable complexity.

7.4. Work Queue Distribution

With Kafka 4.2’s native queue support, you can implement traditional work-queue patterns where tasks are distributed among competing consumers. This is perfect for batch processing, background jobs, and task distribution scenarios that previously required separate queue infrastructure like RabbitMQ or ActiveMQ. Now you get queue semantics with Kafka’s operational benefits.

8. The Migration Path

8.1. Strangler Fig Pattern

You do not need to rip out your ESB overnight. Apply the strangler fig pattern. Identify new integrations or integrations that need significant changes. Implement these as microservices with Kafka instead of ESB flows. Gradually migrate existing integrations as they require updates.

Over time, the ESB shrinks while your Kafka ecosystem grows. Eventually, the ESB becomes small enough to eliminate entirely.

8.2. Event Gateway

Deploy a Kafka-to-ESB bridge for transition periods. Services publish events to Kafka. The bridge consumes these events and forwards them to ESB endpoints where necessary. This allows new services to be built on Kafka while maintaining compatibility with legacy ESB integrations.

8.3. Invest in Platform Engineering

Build internal platforms and tooling around your Kafka and microservices architecture. Provide templates, generators, and golden-path patterns that make it easier to build microservices correctly than to add another ESB flow.

Platform engineering accelerates the migration by making the right way the easy way.

9. The Cost Reality

Organizations often justify ESBs based on licensing costs versus building custom integrations. This analysis is fundamentally flawed.

ESB licenses are expensive, but that is just the beginning. Add the cost of specialized consultants. Add the cost of extended release cycles. Add the opportunity cost of features not delivered because teams are blocked on ESB changes. Add the cost of outages when the ESB fails.

Kafka is open source with zero licensing costs. Spring is open source. Java is free. The tooling ecosystem is mature and open source. Your costs shift from licensing to engineering time, but that engineering time produces assets you own and can evolve without vendor dependency.

More critically, the business velocity enabled by microservices and Kafka translates directly to revenue. Features ship faster. Systems scale to meet demand. You capture opportunities that ESB architectures would have missed.

10. Conclusion

The ESB is a relic of an era when centralization seemed like the answer to complexity. We now know that centralization creates brittleness, bottlenecks, and business risk.

Kafka and microservices represent a fundamentally better approach. Distributed ownership, independent scalability, fault isolation, and evolutionary architecture are not just technical benefits. They are business imperatives in a world where velocity and resilience determine winners and losers.

The question is not whether to move away from ESBs. The question is how quickly you can execute that transition before your ESB becomes an existential business risk. Every day you remain on an ESB architecture is a day your competitors gain ground with more agile, scalable systems.

The death of the ESB is not a tragedy. It is an opportunity to build systems that actually work at the scale and pace modern business demands. Java, Spring, and Kafka provide the foundation for that future. The only question is whether you will embrace it before it is too late.