1. Introduction

Java’s concurrency model has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the introduction of Virtual Threads in Java 19 (as a preview feature) and their stabilization in Java 21. With Java 25, virtual threads have reached new levels of maturity by addressing critical pinning issues that previously limited their effectiveness. This article explores the evolution of threading models in Java, the problems virtual threads solve, and how Java 25 has refined this powerful concurrency primitive.

Virtual threads represent a paradigm shift in how we write concurrent Java applications. They enable the traditional thread per request model to scale to millions of concurrent operations without the resource overhead that plagued platform threads. Understanding virtual threads is essential for modern Java developers building high throughput, scalable applications.

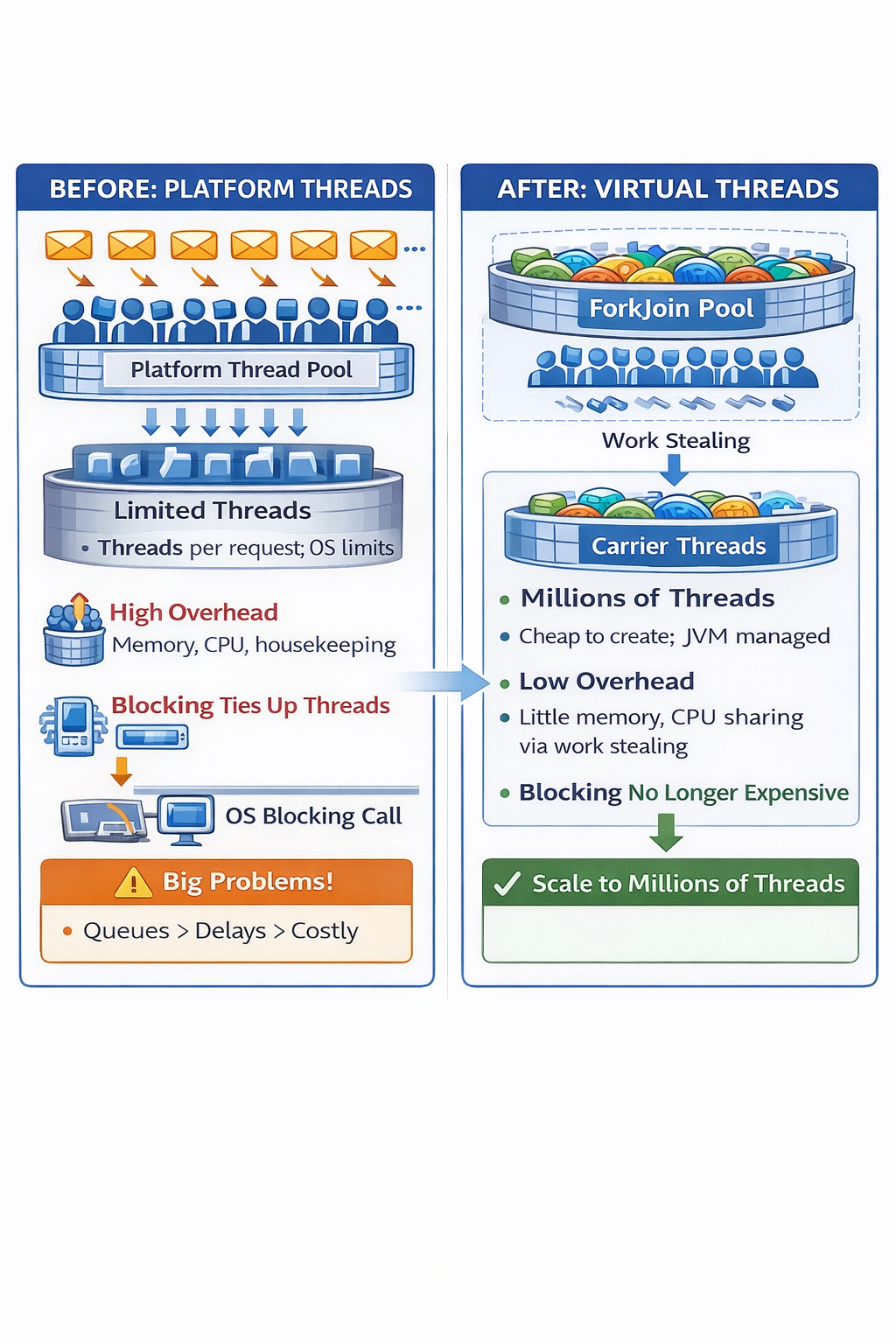

2. The Problem with Traditional Platform Threads

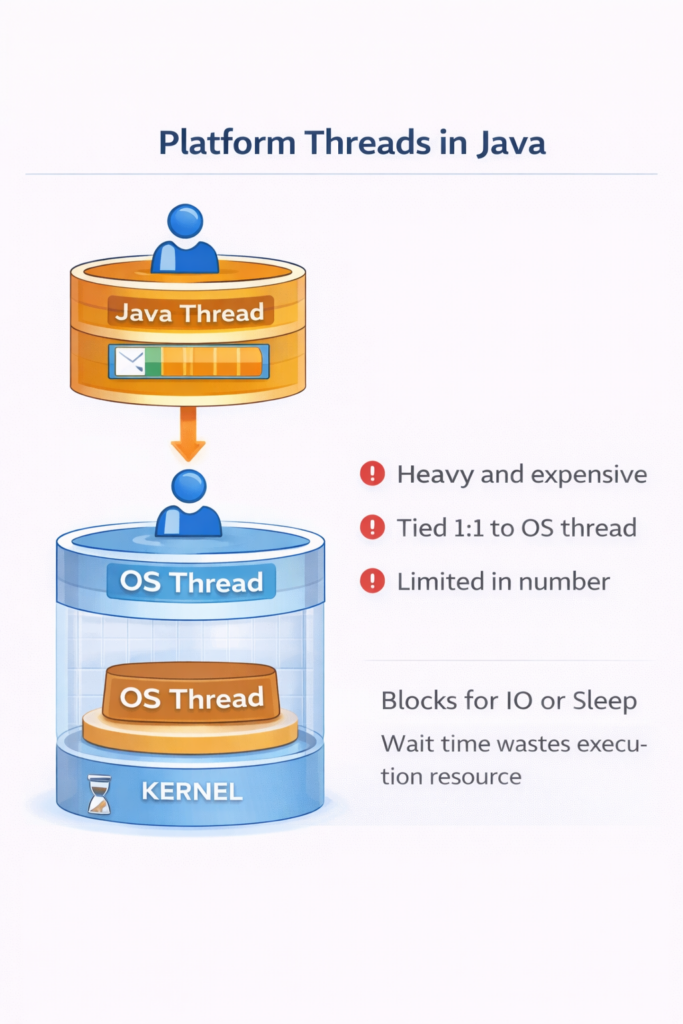

2.1. Platform Thread Architecture

Platform threads (also called OS threads or kernel threads) are the traditional concurrency mechanism in Java. Each Java thread is a thin wrapper around an operating system thread, which looks like:

2.2. Resource Constraints

Platform threads are expensive resources:

- Memory Overhead: Each platform thread requires a stack (typically 1MB by default), which means 1,000 threads consume approximately 1GB of memory just for stacks.

- Context Switching Cost: The OS scheduler must perform context switches between threads, saving and restoring CPU registers, memory mappings, and other state.

- Limited Scalability: Creating tens of thousands of platform threads leads to:

- Memory exhaustion

- Increased context switching overhead

- CPU cache thrashing

- Scheduler contention

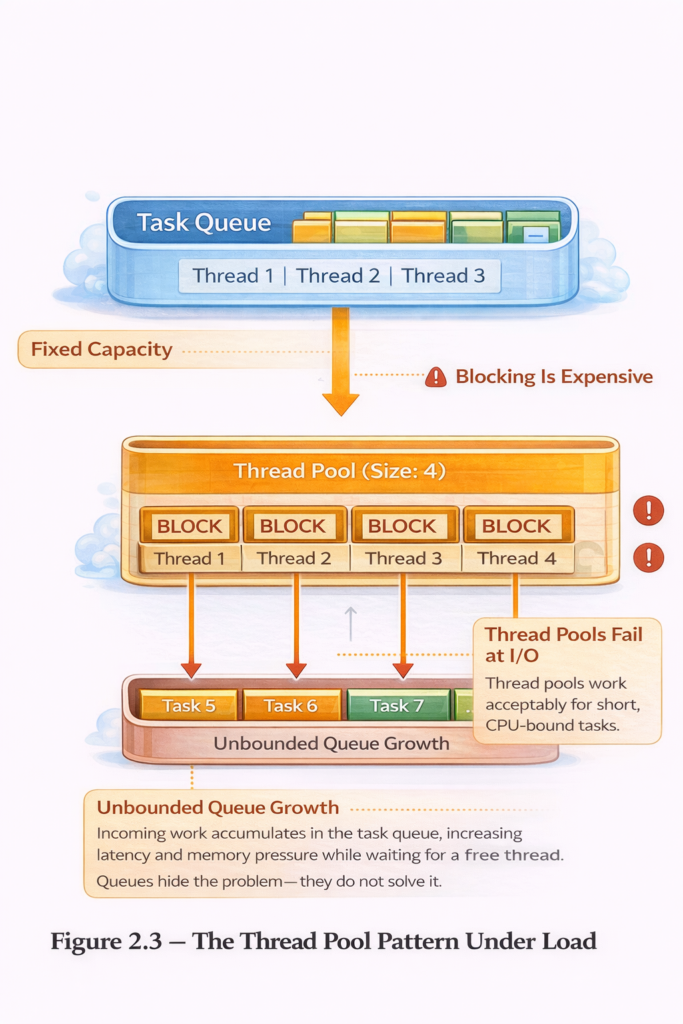

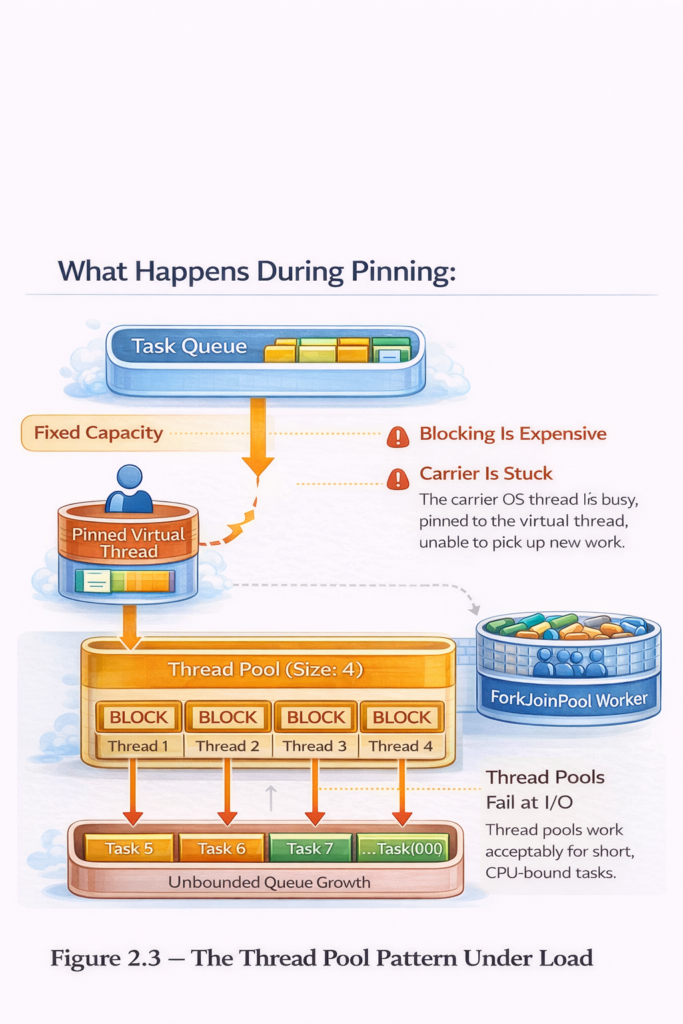

2.3. The Thread Pool Pattern and Its Limitations

To manage these constraints, developers traditionally use thread pools:

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(200);

// Submit tasks to the pool

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

// Perform I/O operation

String data = fetchDataFromDatabase();

processData(data);

});

}

Problems with Thread Pools:

- Task Queuing: With limited threads, tasks queue up waiting for available threads

- Resource Underutilization: Threads blocked on I/O waste CPU time

- Complexity: Tuning pool sizes becomes an art form

- Poor Observability: Stack traces don’t reflect actual application structure

2.4. The Reactive Programming Alternative

To avoid blocking threads, reactive programming emerged:

Mono.fromCallable(() -> fetchDataFromDatabase())

.flatMap(data -> processData(data))

.flatMap(result -> saveToDatabase(result))

.subscribe(

success -> log.info("Completed"),

error -> log.error("Failed", error)

);

Reactive Programming Challenges:

- Steep Learning Curve: Requires understanding operators like flatMap, zip, merge

- Difficult Debugging: Stack traces are fragmented and hard to follow

- Imperative to Declarative: Forces a complete mental model shift

- Library Compatibility: Not all libraries support reactive patterns

- Error Handling: Becomes significantly more complex

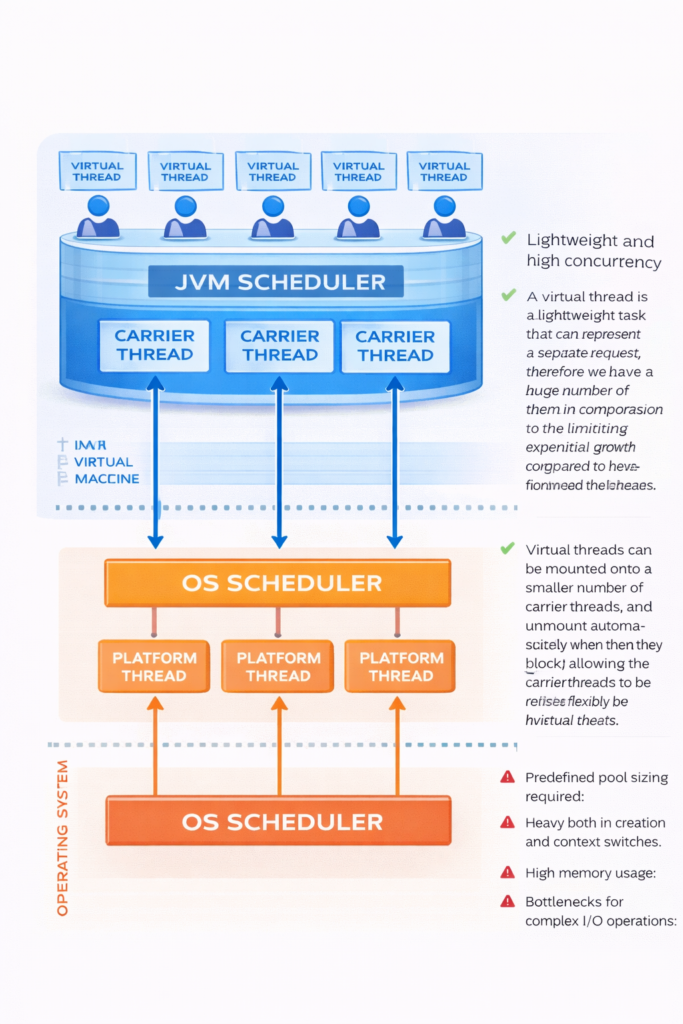

3. Enter Virtual Threads: Lightweight Concurrency

3.1. The Virtual Thread Concept

Virtual threads are lightweight threads managed by the JVM rather than the operating system. They enable the thread per task programming model to scale:

Key Characteristics:

- Cheap to Create: Creating a virtual thread takes microseconds and minimal memory

- JVM Managed: The JVM scheduler multiplexes virtual threads onto a small pool of OS threads (carrier threads)

- Blocking is Fine: When a virtual thread blocks on I/O, the JVM unmounts it from its carrier thread

- Millions Scale: You can create millions of virtual threads without exhausting memory

3.2. How Virtual Threads Work Under the Hood

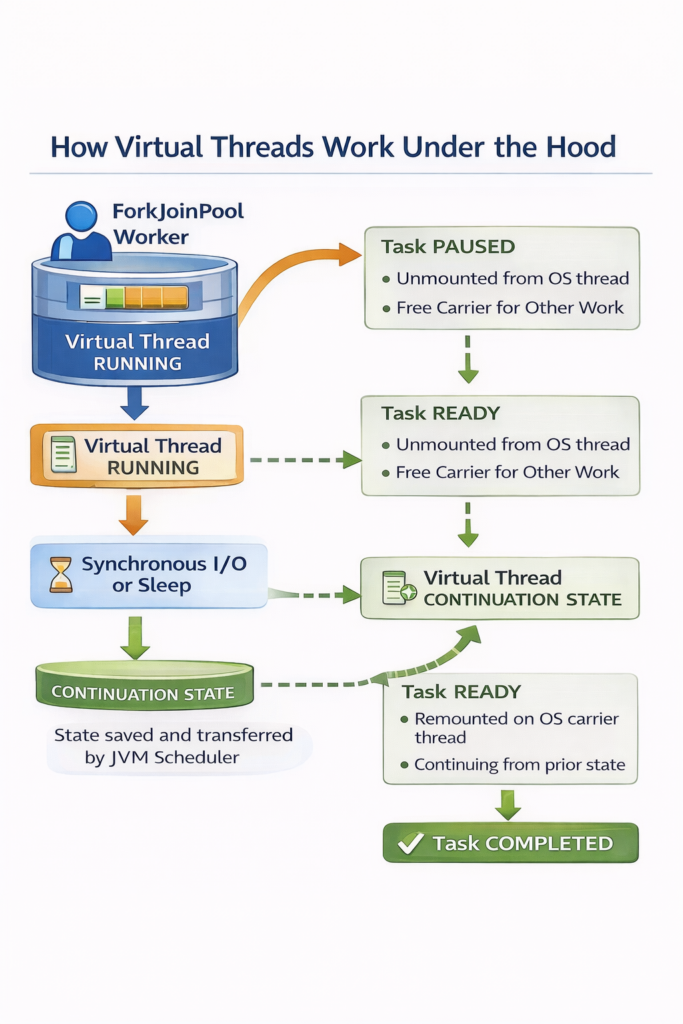

The key innovation of virtual threads lies in how they interact with carrier threads. Understanding this mechanism is essential to grasping why virtual threads scale so effectively.

The Mount and Unmount Cycle

Virtual threads don’t run directly on the CPU. Instead, they temporarily “mount” onto platform threads called carrier threads. When a virtual thread needs to perform actual computation, the JVM assigns it to an available carrier thread. When it blocks on I/O or other operations, the virtual thread “unmounts,” freeing that carrier thread to run other virtual threads.

This mounting and unmounting happens automatically and transparently. The diagram below illustrates this cycle:

Step by Step Process:

- Initial State: Multiple virtual threads (VT1, VT2, VT3) exist in memory, ready to execute. A small pool of carrier threads (platform threads) waits to execute work.

- Mounting: VT1 mounts onto Carrier Thread 1 and begins executing code. The virtual thread now has access to CPU resources through its carrier.

- Blocking Operation: VT1 encounters a blocking operation (like

Thread.sleep(), a database query, or an HTTP request). Rather than forcing the carrier thread to wait idly, the JVM saves VT1’s execution state. - Unmounting: VT1 unmounts from Carrier Thread 1, which immediately becomes available for other work. The carrier thread is now free to run VT2 or VT3.

- Continuation: While VT1 waits for its I/O operation to complete, VT2 can mount onto the same Carrier Thread 1 and begin executing. One carrier thread can effectively support hundreds or thousands of virtual threads by rapidly switching between them whenever they block.

- Remounting: When VT1’s blocking operation completes (the database responds, the sleep finishes, etc.), VT1 becomes eligible to run again. The JVM schedules it onto any available carrier thread—not necessarily the same one it used before—restores its saved state, and execution continues from where it left off.

This cycle repeats continuously. Virtual threads spend most of their time unmounted, consuming minimal resources. They only occupy carrier threads during active computation, allowing a small number of carrier threads to support millions of virtual threads efficiently.

Why This Matters

Traditional platform threads would block the underlying OS thread during I/O operations, wasting valuable CPU time. Virtual threads eliminate this waste by releasing the carrier thread immediately upon blocking. This is why you can have a million virtual threads but only need a handful of carrier threads—most virtual threads are waiting for I/O at any given moment, not performing computation.

The next section explores the continuation mechanism that makes this mounting and unmounting possible.. The Continuation Mechanism

Virtual threads use a mechanism called continuations. Below is an explanation of the continuation mechanism:

- A virtual thread begins executing on some carrier (an OS thread under the hood), as though it were a normal thread.

- When it hits a blocking operation (I/O, sleep, etc), the runtime arranges to save where it is (its stack frames, locals) into a continuation object (or the equivalent mechanism).

- That carrier thread is released (so it can run other virtual threads) while the virtual thread is waiting.

- Later when the blocking completes / the virtual thread is ready to resume, the continuation is scheduled on some carrier thread, its state restored and execution continues.

A simplified conceptual model looks like this:

// Simplified conceptual representation

class VirtualThread {

Continuation continuation;

Object mountedCarrierThread;

void park() {

// Save execution state

continuation.yield();

// Unmount from carrier thread

mountedCarrierThread = null;

}

void unpark() {

// Find available carrier thread

mountedCarrierThread = getAvailableCarrier();

// Restore execution state

continuation.run();

}

}

4. Creating and Using Virtual Threads

4.1. Basic Virtual Thread Creation

// Method 1: Using Thread.ofVirtual()

Thread vThread = Thread.ofVirtual().start(() -> {

System.out.println("Hello from virtual thread: " +

Thread.currentThread());

});

vThread.join();

// Method 2: Using Thread.startVirtualThread()

Thread.startVirtualThread(() -> {

System.out.println("Another virtual thread: " +

Thread.currentThread());

});

// Method 3: Using ExecutorService

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

executor.submit(() -> {

System.out.println("Virtual thread from executor: " +

Thread.currentThread());

});

}

4.2. Virtual Thread Properties

Thread vThread = Thread.ofVirtual()

.name("my-virtual-thread")

.unstarted(() -> {

System.out.println("Thread name: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

System.out.println("Is virtual: " + Thread.currentThread().isVirtual());

});

vThread.start();

vThread.join();

// Output:

// Thread name: my-virtual-thread

// Is virtual: true

4.3. Practical Example: HTTP Server

This example shows how virtual threads simplify server design by allowing each incoming HTTP request to be handled in its own virtual thread, just like the classic thread-per-request model—only now it scales.

The code below creates an executor that launches a new virtual thread for every request. Inside that thread, the handler performs blocking I/O (reading the request and writing the response) in a natural, linear style. There’s no need for callbacks, reactive chains, or custom thread pools, because blocking no longer ties up an OS thread.

Each request runs independently, errors are isolated, and the system can support a very large number of concurrent connections thanks to the low cost of virtual threads.

The new virtual thread version is dramatically simpler because it uses plain blocking code without threadpool tuning, callback handlers, or complex asynchronous frameworks.

// Traditional Platform Thread Approach

public class PlatformThreadServer {

private static final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(200);

public void handleRequest(HttpRequest request) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

// Simulate database query (blocking I/O)

Thread.sleep(100);

String data = queryDatabase(request);

// Simulate external API call (blocking I/O)

Thread.sleep(50);

String apiResult = callExternalApi(data);

sendResponse(apiResult);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

}

}

// Virtual Thread Approach

public class VirtualThreadServer {

private static final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

public void handleRequest(HttpRequest request) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

// Same blocking code, but now scalable!

Thread.sleep(100);

String data = queryDatabase(request);

Thread.sleep(50);

String apiResult = callExternalApi(data);

sendResponse(apiResult);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

}

}

Performance Comparison:

Platform Thread Server (200 thread pool):

- Max concurrent requests: ~200

- Memory overhead: ~200MB (thread stacks)

- Throughput: Limited by pool size

Virtual Thread Server:

- Max concurrent requests: ~1,000,000+

- Memory overhead: ~1MB per 1000 threads

- Throughput: Limited by available I/O resources

4.4. Structured Concurrency

Traditional Java concurrency makes it easy to start threads but hard to control their lifecycle. Tasks can outlive the method that created them, failures get lost, and background work becomes difficult to reason about.

Structured concurrency fixes this by enforcing a simple rule:

tasks started in a scope must finish before the scope exits.

This gives you predictable ownership, automatic cleanup, and reliable error propagation.

With virtual threads, this model finally becomes practical. Virtual threads are cheap to create and safe to block, so you can express concurrent logic using straightforward, synchronous-looking code—without thread pools or callbacks.

Example

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

var f1 = scope.fork(() -> fetchUser(id));

var f2 = scope.fork(() -> fetchOrders(id));

scope.join();

scope.throwIfFailed();

return new UserData(f1.get(), f2.get());

}All tasks run concurrently, but the structure remains clear:

- the parent waits for all children,

- failures propagate correctly,

- and no threads leak beyond the scope.

In short: virtual threads provide the scalability; structured concurrency provides the clarity. Together they make concurrent Java code simple, safe, and predictable.

5. Issues with Virtual Threads Before Java 25

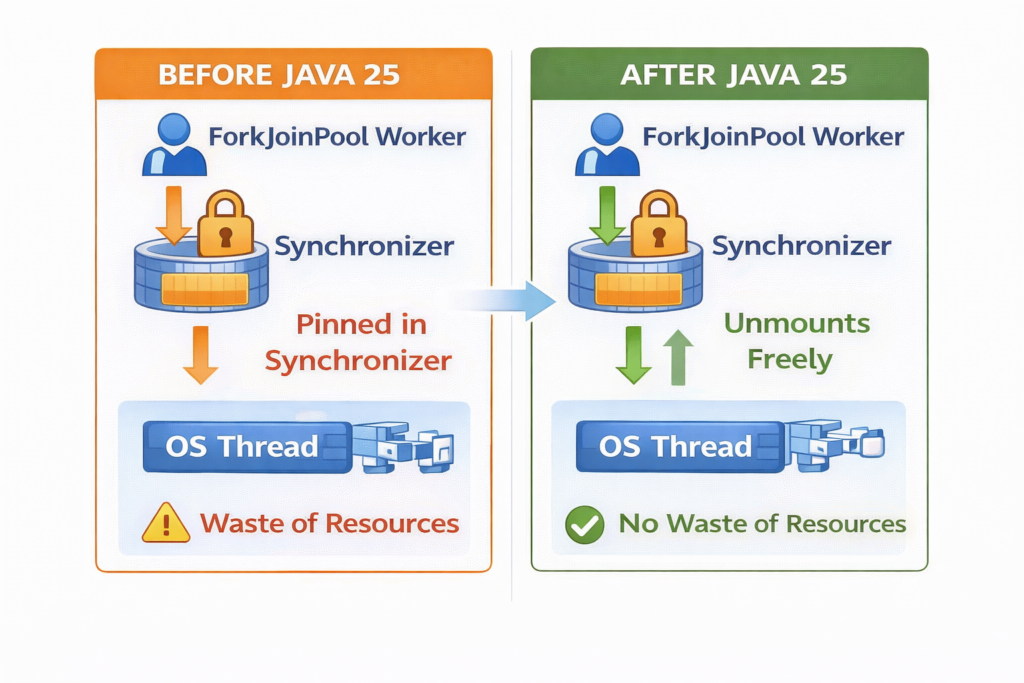

5.1. The Pinning Problem

The most significant issue with virtual threads before Java 25 was “pinning” – situations where a virtual thread could not unmount from its carrier thread when blocking, defeating the purpose of virtual threads.

Pinning occurred in two main scenarios:

5.1.1. Synchronized Blocks

public class PinningExample {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void problematicMethod() {

synchronized (lock) { // PINNING OCCURS HERE

try {

// This sleep pins the carrier thread

Thread.sleep(1000);

// I/O operations also pin

String data = blockingDatabaseCall();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

What happens during pinning:

5.1.2. Native Methods and Foreign Functions

public class NativePinningExample {

public void callNativeCode() {

// JNI calls pin the virtual thread

nativeMethod(); // PINNING

}

private native void nativeMethod();

public void foreignFunctionCall() {

// Foreign function calls (Project Panama) also pin

try (Arena arena = Arena.ofConfined()) {

MemorySegment segment = arena.allocate(100);

// Operations here may pin

}

}

}

5.2. Monitoring Pinning Events

Before Java 25, you could detect pinning with JVM flags:

java -Djdk.tracePinnedThreads=full MyApplication

Output when pinning occurs:

Thread[#23,ForkJoinPool-1-worker-1,5,CarrierThreads]

java.base/java.lang.VirtualThread$VThreadContinuation.onPinned

java.base/java.lang.VirtualThread.parkNanos

java.base/java.lang.System$2.parkVirtualThread

java.base/jdk.internal.misc.VirtualThreads.park

java.base/java.lang.Thread.sleepNanos

com.example.MyClass.problematicMethod(MyClass.java:42) <== monitors:1

5.3. Workarounds Before Java 25

Developers had to manually refactor code to avoid pinning:

// BAD: Uses synchronized (causes pinning)

public class BadExample {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void processRequest() {

synchronized (lock) {

blockingOperation(); // PINNING

}

}

}

// GOOD: Uses ReentrantLock (no pinning)

public class GoodExample {

private final ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void processRequest() {

lock.lock();

try {

blockingOperation(); // No pinning

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

5.4. Impact of Pinning

The pinning problem had severe consequences:

// Demonstration of pinning impact

public class PinningImpactDemo {

private static final Object LOCK = new Object();

public static void main(String[] args) {

int numTasks = 10000;

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numTasks);

for (int i = 0; i < numTasks; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

synchronized (LOCK) { // All threads pin on this lock

try {

Thread.sleep(10);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

latch.countDown();

});

}

latch.await();

long duration = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

System.out.println("Time with synchronized: " + duration + "ms");

// Result: ~Sequential execution due to pinning

}

}

}

Results:

- With synchronized (pinning): ~100 seconds (essentially sequential)

- With ReentrantLock (no pinning): ~1 second (highly concurrent)

6. Java 25 Improvements: Solving the Pinning Problem

6.1. JEP 491: Synchronized Blocks No Longer Pin

Java 25 introduces a revolutionary change through JEP 491: synchronized blocks and methods no longer pin virtual threads to their carrier threads.

How it works:

Java 21-24 Behavior:

┌─────────────┐

│Virtual │

│Thread │ ─ synchronized block ─> PINS carrier thread

└─────┬───────┘

│ PINNED

↓

┌─────────────┐

│Carrier │ ← Cannot be reused

│Thread │

└─────────────┘

Java 25+ Behavior:

┌─────────────┐

│Virtual │

│Thread │ ─ synchronized block ─> Unmounts normally

└─────────────┘

│

↓ Unmounts

┌─────────────┐

│Carrier │ ← Available for other virtual threads

│Thread (FREE)│

└─────────────┘

6.2. Implementation Details

The JVM now uses a new locking mechanism that allows virtual threads to yield even inside synchronized blocks:

public class Java25SynchronizedExample {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void modernSynchronized() {

synchronized (lock) {

// In Java 25+, this blocking operation

// will NOT pin the carrier thread

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

// I/O operations also don't pin anymore

String data = blockingDatabaseCall();

processData(data);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

// Virtual thread can unmount and remount as needed

}

private String blockingDatabaseCall() {

// Simulated blocking I/O

return "data";

}

private void processData(String data) {

// Processing

}

}

6.3. Performance Improvements

Let’s compare the same workload across Java versions:

public class PerformanceComparison {

private static final Object SHARED_LOCK = new Object();

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

int numTasks = 10000;

int sleepMs = 10;

// Test with synchronized blocks

testSynchronized(numTasks, sleepMs);

}

private static void testSynchronized(int numTasks, int sleepMs)

throws InterruptedException {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numTasks);

for (int i = 0; i < numTasks; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

synchronized (SHARED_LOCK) {

try {

Thread.sleep(sleepMs);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

latch.countDown();

});

}

latch.await();

long duration = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

System.out.println("Synchronized block test:");

System.out.println(" Tasks: " + numTasks);

System.out.println(" Duration: " + duration + "ms");

System.out.println(" Throughput: " + (numTasks * 1000.0 / duration) + " tasks/sec");

}

}

}

Results:

Java 21-24:

Tasks: 10000

Duration: ~100000ms (essentially sequential)

Throughput: ~100 tasks/sec

Java 25:

Tasks: 10000

Duration: ~1000ms (highly parallel)

Throughput: ~10000 tasks/sec

100x performance improvement!

6.4. No More Manual Refactoring

Before Java 25, libraries and applications had to refactor synchronized code:

// Pre-Java 25: Had to refactor to avoid pinning

public class PreJava25Approach {

// Changed from Object to ReentrantLock

private final ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void doWork() {

lock.lock(); // More verbose

try {

blockingOperation();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

// Java 25+: Can keep existing synchronized code

public class Java25Approach {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public synchronized void doWork() { // Simple, no pinning

blockingOperation();

}

}

6.5. Remaining Pinning Scenarios

Java 25 removes most cases where virtual threads could become pinned, but a few situations can still prevent a virtual thread from unmounting from its carrier thread:

1. Blocking Native Calls (JNI)

If a virtual thread enters a JNI method that blocks, the JVM cannot safely suspend it, so the carrier thread remains pinned until the native call returns.

2. Synchronized Blocks Leading Into Native Work

Although Java-level synchronization no longer pins, a synchronized section that transitions into a blocking native operation can still force the carrier thread to stay attached.

3. Low-Level APIs Requiring Thread Affinity

Code using Unsafe, custom locks, or mechanisms that assume a fixed OS thread may require pinning to maintain correctness.

6.6. Migration Benefits

Existing codebases automatically benefit from Java 25:

// Legacy code using synchronized (common in older libraries)

public class LegacyService {

private final Map<String, Data> cache = new HashMap<>();

public synchronized Data getData(String key) {

if (!cache.containsKey(key)) {

// This would pin in Java 21-24

// No pinning in Java 25!

Data data = expensiveDatabaseCall(key);

cache.put(key, data);

}

return cache.get(key);

}

private Data expensiveDatabaseCall(String key) {

// Blocking I/O

return new Data();

}

record Data() {}

}

7. Understanding ForkJoinPool and Virtual Thread Scheduling

Virtual threads behave as if each one runs independently, but they do not execute directly on the CPU. Instead, the JVM schedules them onto a small set of real OS threads known as carrier threads. These carrier threads are managed by the ForkJoinPool, which serves as the internal scheduler that runs, pauses, and resumes virtual threads.

This scheduling model allows Java to scale to massive levels of concurrency without overwhelming the operating system.

7.1 What the ForkJoinPool Is

The ForkJoinPool is a high-performance thread pool built around a small number of long-lived worker threads. It was originally designed for parallel computations but is also ideal for running virtual threads because of its extremely efficient scheduling behaviour.

Each worker thread maintains its own task queue, allowing most operations to happen without contention. The pool is designed to keep all CPU cores busy with minimal overhead.

7.2 The Work-Stealing Algorithm

A defining feature of the ForkJoinPool is its work-stealing algorithm. Each worker thread primarily works from its own queue, but when it becomes idle, it doesn’t wait—it looks for work in other workers’ queues.

In other words:

- Active workers process their own tasks.

- Idle workers “steal” tasks from other queues.

- Stealing avoids bottlenecks and keeps all CPU cores busy.

- Tasks spread dynamically across the pool, improving throughput.

This decentralized approach avoids the cost of a single shared queue and ensures that no CPU thread sits idle while others still have work.

Work-stealing is one of the main reasons the ForkJoinPool can handle huge numbers of virtual threads efficiently.

7.3 Why Virtual Threads Use the ForkJoinPool

Virtual threads frequently block during operations like I/O, sleeping, or locking. When a virtual thread blocks, the JVM can save its execution state and immediately free the carrier thread.

To make this efficient, Java needs a scheduler that can:

- quickly reassign work to available carrier threads

- keep CPUs fully utilized

- handle thousands or millions of short-lived tasks

- pick up paused virtual threads instantly when they resume

The ForkJoinPool, with its lightweight scheduling and work-stealing algorithm, suited these needs perfectly.

7.4 How Virtual Thread Scheduling Works

The scheduling process works as follows:

- A virtual thread becomes runnable.

- The ForkJoinPool assigns it to an available carrier thread.

- The virtual thread executes until it blocks.

- The JVM captures its state and unmounts it, freeing the carrier thread.

- When the blocking operation completes, the virtual thread is placed back into the pool’s queues.

- Any available carrier thread—regardless of which one ran it earlier—can resume it.

Because virtual threads run only when actively computing, and unmount the moment they block, the ForkJoinPool keeps the system efficient and responsive.

7.5 Why This Design Scales

This architecture scales exceptionally well:

- Few OS threads handle many virtual threads.

- Blocking is cheap, because it releases carrier threads instantly.

- Work-stealing ensures every CPU is busy and load-balanced.

- Context switching is lightweight compared to OS thread switching.

- Developers write simple blocking code, without worrying about thread pool exhaustion.

It gives Java the scalability of an asynchronous runtime with the readability of synchronous code.

7.6 Misconceptions About the ForkJoinPool

Although virtual threads rely on a ForkJoinPool internally, they do not interfere with:

- parallel streams,

- custom ForkJoinPools created by the application,

- or other thread pools.

The virtual-thread scheduler is isolated, and it normally requires no configuration or tuning.

The ForkJoinPool, powered by its work-stealing algorithm, provides the small number of OS threads and the efficient scheduling needed to run them at scale. Together, they allow Java to deliver enormous concurrency without the complexity or overhead of traditional threading models.

8. Virtual Threads vs. Reactive Programming

8.1. Code Complexity Comparison

// Scenario: Fetch user data, enrich with profile, save to database

// Reactive approach (Spring WebFlux)

public class ReactiveUserService {

public Mono<User> processUser(String userId) {

return userRepository.findById(userId)

.flatMap(user ->

profileService.getProfile(user.getProfileId())

.map(profile -> user.withProfile(profile))

)

.flatMap(user ->

enrichmentService.enrichData(user)

)

.flatMap(user ->

userRepository.save(user)

)

.doOnError(error ->

log.error("Error processing user", error)

)

.timeout(Duration.ofSeconds(5))

.retry(3);

}

}

// Virtual thread approach (Spring Boot with Virtual Threads)

public class VirtualThreadUserService {

public User processUser(String userId) {

try {

// Simple, sequential code that scales

User user = userRepository.findById(userId);

Profile profile = profileService.getProfile(user.getProfileId());

user = user.withProfile(profile);

user = enrichmentService.enrichData(user);

return userRepository.save(user);

} catch (Exception e) {

log.error("Error processing user", e);

throw e;

}

}

}

8.2. Error Handling Comparison

// Reactive error handling

public Mono<Result> reactiveProcessing() {

return fetchData()

.flatMap(data -> validate(data))

.flatMap(data -> process(data))

.onErrorResume(ValidationException.class, e ->

Mono.just(Result.validationFailed(e)))

.onErrorResume(ProcessingException.class, e ->

Mono.just(Result.processingFailed(e)))

.onErrorResume(e ->

Mono.just(Result.unknownError(e)));

}

// Virtual thread error handling

public Result virtualThreadProcessing() {

try {

Data data = fetchData();

validate(data);

return process(data);

} catch (ValidationException e) {

return Result.validationFailed(e);

} catch (ProcessingException e) {

return Result.processingFailed(e);

} catch (Exception e) {

return Result.unknownError(e);

}

}

8.3. When to Use Each Approach

Use Virtual Threads When:

- You want simple, readable code

- Your team is familiar with imperative programming

- You need easy debugging with clear stack traces

- You’re working with blocking APIs

- You want to migrate existing code with minimal changes

Consider Reactive When:

- You need backpressure handling

- You’re building streaming data pipelines

- You need fine grained control over execution

- Your entire stack is already reactive

9. Advanced Virtual Thread Patterns

9.1. Fan Out / Fan In Pattern

public class FanOutFanInPattern {

public CompletedReport generateReport(List<String> dataSourceIds) throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

// Fan out: Submit tasks for each data source

List<Subtask<DataChunk>> tasks = dataSourceIds.stream()

.map(id -> scope.fork(() -> fetchFromDataSource(id)))

.toList();

// Wait for all to complete

scope.join();

scope.throwIfFailed();

// Fan in: Combine results

List<DataChunk> allData = tasks.stream()

.map(Subtask::get)

.toList();

return aggregateReport(allData);

}

}

private DataChunk fetchFromDataSource(String id) throws InterruptedException {

Thread.sleep(100); // Simulate I/O

return new DataChunk(id, "Data from " + id);

}

private CompletedReport aggregateReport(List<DataChunk> chunks) {

return new CompletedReport(chunks);

}

record DataChunk(String sourceId, String data) {}

record CompletedReport(List<DataChunk> chunks) {}

}

9.2. Rate Limited Processing

public class RateLimitedProcessor {

private final Semaphore rateLimiter;

private final ExecutorService executor;

public RateLimitedProcessor(int maxConcurrent) {

this.rateLimiter = new Semaphore(maxConcurrent);

this.executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

}

public void processItems(List<Item> items) throws InterruptedException {

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(items.size());

for (Item item : items) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

rateLimiter.acquire();

try {

processItem(item);

} finally {

rateLimiter.release();

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

});

}

latch.await();

}

private void processItem(Item item) throws InterruptedException {

Thread.sleep(50); // Simulate processing

System.out.println("Processed: " + item.id());

}

public void shutdown() {

executor.close();

}

record Item(String id) {}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

RateLimitedProcessor processor = new RateLimitedProcessor(10);

List<Item> items = IntStream.range(0, 100)

.mapToObj(i -> new Item("item-" + i))

.toList();

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

processor.processItems(items);

long duration = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

System.out.println("Processed " + items.size() +

" items in " + duration + "ms");

processor.shutdown();

}

}

9.3. Timeout Pattern

public class TimeoutPattern {

public <T> T executeWithTimeout(Callable<T> task, Duration timeout)

throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

Subtask<T> subtask = scope.fork(task);

// Join with timeout

scope.joinUntil(Instant.now().plus(timeout));

if (subtask.state() == Subtask.State.SUCCESS) {

return subtask.get();

} else {

throw new TimeoutException("Task did not complete within " + timeout);

}

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

TimeoutPattern pattern = new TimeoutPattern();

try {

String result = pattern.executeWithTimeout(

() -> {

Thread.sleep(5000);

return "Completed";

},

Duration.ofSeconds(2)

);

System.out.println("Result: " + result);

} catch (TimeoutException e) {

System.out.println("Task timed out!");

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

9.4. Racing Tasks Pattern

public class RacingTasksPattern {

public <T> T race(List<Callable<T>> tasks) throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnSuccess<T>()) {

// Submit all tasks

for (Callable<T> task : tasks) {

scope.fork(task);

}

// Wait for first success

scope.join();

// Return the first result

return scope.result();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

RacingTasksPattern pattern = new RacingTasksPattern();

List<Callable<String>> tasks = List.of(

() -> {

Thread.sleep(1000);

return "Server 1 response";

},

() -> {

Thread.sleep(500);

return "Server 2 response";

},

() -> {

Thread.sleep(2000);

return "Server 3 response";

}

);

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

String result = pattern.race(tasks);

long duration = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

System.out.println("Winner: " + result);

System.out.println("Time: " + duration + "ms");

// Output: Winner: Server 2 response, Time: ~500ms

}

}

10. Best Practices and Gotchas

10.1. ThreadLocal Considerations

Virtual threads and ThreadLocal can lead to memory issues:

public class ThreadLocalIssues {

// PROBLEM: ThreadLocal with virtual threads

private static final ThreadLocal<ExpensiveResource> resource =

ThreadLocal.withInitial(ExpensiveResource::new);

public void problematicUsage() {

// With millions of virtual threads, millions of instances!

ExpensiveResource r = resource.get();

r.doWork();

}

// SOLUTION 1: Use scoped values (Java 21+)

private static final ScopedValue<ExpensiveResource> scopedResource =

ScopedValue.newInstance();

public void betterUsage() {

ExpensiveResource r = new ExpensiveResource();

ScopedValue.where(scopedResource, r).run(() -> {

ExpensiveResource scoped = scopedResource.get();

scoped.doWork();

});

}

// SOLUTION 2: Pass as parameters

public void bestUsage(ExpensiveResource resource) {

resource.doWork();

}

static class ExpensiveResource {

private final byte[] data = new byte[1024 * 1024]; // 1MB

void doWork() {

// Work with resource

}

}

}

10.2. Don’t Block the Carrier Thread Pool

public class CarrierThreadPoolGotchas {

// BAD: CPU intensive work in virtual threads

public void cpuIntensiveWork() {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

// This blocks a carrier thread with CPU work

computePrimes(1_000_000);

});

}

}

}

// GOOD: Use platform thread pool for CPU work

public void properCpuWork() {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(

Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors())) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

computePrimes(1_000_000);

});

}

}

}

// VIRTUAL THREADS: Best for I/O bound work

public void ioWork() {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1_000_000; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

// I/O operations: perfect for virtual threads

String data = fetchFromDatabase();

sendToAPI(data);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

});

}

}

}

private void computePrimes(int limit) {

// CPU intensive calculation

for (int i = 2; i < limit; i++) {

boolean isPrime = true;

for (int j = 2; j <= Math.sqrt(i); j++) {

if (i % j == 0) {

isPrime = false;

break;

}

}

}

}

private String fetchFromDatabase() {

return "data";

}

private void sendToAPI(String data) {

// API call

}

}

10.3. Monitoring and Observability

public class VirtualThreadMonitoring {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

// Enable virtual thread events

System.setProperty("jdk.tracePinnedThreads", "full");

// Get thread metrics

ThreadMXBean threadBean = ManagementFactory.getThreadMXBean();

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

// Submit many tasks

List<Future<?>> futures = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

futures.add(executor.submit(() -> {

try {

Thread.sleep(100);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}));

}

// Monitor while tasks execute

Thread.sleep(50);

System.out.println("Thread count: " + threadBean.getThreadCount());

System.out.println("Peak threads: " + threadBean.getPeakThreadCount());

// Wait for completion

for (Future<?> future : futures) {

future.get();

}

}

System.out.println("Final thread count: " + threadBean.getThreadCount());

}

}

10.4. Structured Concurrency Best Practices

public class StructuredConcurrencyBestPractices {

// GOOD: Properly structured with clear lifecycle

public Result processWithStructure() throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

Subtask<Data> dataTask = scope.fork(this::fetchData);

Subtask<Config> configTask = scope.fork(this::fetchConfig);

scope.join();

scope.throwIfFailed();

return new Result(dataTask.get(), configTask.get());

} // Scope ensures all tasks complete or are cancelled

}

// BAD: Unstructured concurrency (avoid)

public Result processWithoutStructure() {

CompletableFuture<Data> dataFuture =

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::fetchData);

CompletableFuture<Config> configFuture =

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::fetchConfig);

// No clear lifecycle, potential resource leaks

return new Result(

dataFuture.join(),

configFuture.join()

);

}

private Data fetchData() {

return new Data();

}

private Config fetchConfig() {

return new Config();

}

record Data() {}

record Config() {}

record Result(Data data, Config config) {}

}

11. Real World Use Cases

11.1. Web Server with Virtual Threads

// Spring Boot 3.2+ with Virtual Threads

@SpringBootApplication

public class VirtualThreadWebApp {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(VirtualThreadWebApp.class, args);

}

@Bean

public TomcatProtocolHandlerCustomizer<?> protocolHandlerVirtualThreadExecutorCustomizer() {

return protocolHandler -> {

protocolHandler.setExecutor(Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor());

};

}

}

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/api")

class UserController {

@Autowired

private UserService userService;

@GetMapping("/users/{id}")

public ResponseEntity<User> getUser(@PathVariable String id) {

// This runs on a virtual thread

// Blocking calls are fine!

User user = userService.fetchUser(id);

return ResponseEntity.ok(user);

}

@GetMapping("/users/{id}/full")

public ResponseEntity<UserFullProfile> getFullProfile(@PathVariable String id) {

// Multiple blocking calls - no problem with virtual threads

User user = userService.fetchUser(id);

List<Order> orders = userService.fetchOrders(id);

List<Review> reviews = userService.fetchReviews(id);

return ResponseEntity.ok(

new UserFullProfile(user, orders, reviews)

);

}

record User(String id, String name) {}

record Order(String id) {}

record Review(String id) {}

record UserFullProfile(User user, List<Order> orders, List<Review> reviews) {}

}

11.2. Batch Processing System

public class BatchProcessor {

private final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

public BatchResult processBatch(List<Record> records) throws InterruptedException {

int batchSize = 1000;

List<List<Record>> batches = partition(records, batchSize);

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(batches.size());

List<CompletableFuture<BatchResult>> futures = new ArrayList<>();

for (List<Record> batch : batches) {

CompletableFuture<BatchResult> future = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(

() -> {

try {

return processSingleBatch(batch);

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

},

executor

);

futures.add(future);

}

latch.await();

// Combine results

return futures.stream()

.map(CompletableFuture::join)

.reduce(BatchResult.empty(), BatchResult::merge);

}

private BatchResult processSingleBatch(List<Record> batch) {

int processed = 0;

int failed = 0;

for (Record record : batch) {

try {

processRecord(record);

processed++;

} catch (Exception e) {

failed++;

}

}

return new BatchResult(processed, failed);

}

private void processRecord(Record record) {

// Simulate processing with I/O

try {

Thread.sleep(10);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

private <T> List<List<T>> partition(List<T> list, int size) {

List<List<T>> partitions = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < list.size(); i += size) {

partitions.add(list.subList(i, Math.min(i + size, list.size())));

}

return partitions;

}

public void shutdown() {

executor.close();

}

record Record(String id) {}

record BatchResult(int processed, int failed) {

static BatchResult empty() {

return new BatchResult(0, 0);

}

BatchResult merge(BatchResult other) {

return new BatchResult(

this.processed + other.processed,

this.failed + other.failed

);

}

}

}

11.3. Microservice Communication

public class MicroserviceOrchestrator {

private final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

private final HttpClient httpClient = HttpClient.newHttpClient();

public OrderResponse processOrder(OrderRequest request) throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

// Call multiple microservices in parallel

Subtask<Customer> customerTask = scope.fork(

() -> fetchCustomer(request.customerId())

);

Subtask<Inventory> inventoryTask = scope.fork(

() -> checkInventory(request.productId(), request.quantity())

);

Subtask<PaymentResult> paymentTask = scope.fork(

() -> processPayment(request.customerId(), request.amount())

);

Subtask<ShippingQuote> shippingTask = scope.fork(

() -> getShippingQuote(request.address())

);

// Wait for all services to respond

scope.join();

scope.throwIfFailed();

// Create order with all collected data

return createOrder(

customerTask.get(),

inventoryTask.get(),

paymentTask.get(),

shippingTask.get()

);

}

}

private Customer fetchCustomer(String customerId) {

HttpRequest request = HttpRequest.newBuilder()

.uri(URI.create("http://customer-service/api/customers/" + customerId))

.build();

try {

HttpResponse<String> response =

httpClient.send(request, HttpResponse.BodyHandlers.ofString());

return parseCustomer(response.body());

} catch (Exception e) {

throw new RuntimeException("Failed to fetch customer", e);

}

}

private Inventory checkInventory(String productId, int quantity) {

// HTTP call to inventory service

return new Inventory(productId, true);

}

private PaymentResult processPayment(String customerId, double amount) {

// HTTP call to payment service

return new PaymentResult("txn-123", true);

}

private ShippingQuote getShippingQuote(String address) {

// HTTP call to shipping service

return new ShippingQuote(15.99);

}

private Customer parseCustomer(String json) {

return new Customer("cust-1", "John Doe");

}

private OrderResponse createOrder(Customer customer, Inventory inventory,

PaymentResult payment, ShippingQuote shipping) {

return new OrderResponse("order-123", "CONFIRMED");

}

record OrderRequest(String customerId, String productId, int quantity,

double amount, String address) {}

record Customer(String id, String name) {}

record Inventory(String productId, boolean available) {}

record PaymentResult(String transactionId, boolean success) {}

record ShippingQuote(double cost) {}

record OrderResponse(String orderId, String status) {}

}

12. Performance Benchmarks

12.1. Throughput Comparison

public class ThroughputBenchmark {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

int numRequests = 100_000;

int ioDelayMs = 10;

System.out.println("=== Throughput Benchmark ===");

System.out.println("Requests: " + numRequests);

System.out.println("I/O delay per request: " + ioDelayMs + "ms\n");

// Platform threads with fixed pool

benchmarkPlatformThreads(numRequests, ioDelayMs);

// Virtual threads

benchmarkVirtualThreads(numRequests, ioDelayMs);

}

private static void benchmarkPlatformThreads(int numRequests, int ioDelayMs)

throws InterruptedException {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(200)) {

long start = System.nanoTime();

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numRequests);

for (int i = 0; i < numRequests; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

Thread.sleep(ioDelayMs);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

});

}

latch.await();

long duration = System.nanoTime() - start;

double seconds = duration / 1_000_000_000.0;

System.out.println("Platform Threads (200 thread pool):");

System.out.println(" Duration: " + String.format("%.2f", seconds) + "s");

System.out.println(" Throughput: " +

String.format("%.0f", numRequests / seconds) + " req/s\n");

}

}

private static void benchmarkVirtualThreads(int numRequests, int ioDelayMs)

throws InterruptedException {

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

long start = System.nanoTime();

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numRequests);

for (int i = 0; i < numRequests; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

Thread.sleep(ioDelayMs);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

});

}

latch.await();

long duration = System.nanoTime() - start;

double seconds = duration / 1_000_000_000.0;

System.out.println("Virtual Threads:");

System.out.println(" Duration: " + String.format("%.2f", seconds) + "s");

System.out.println(" Throughput: " +

String.format("%.0f", numRequests / seconds) + " req/s\n");

}

}

}

Expected Output:

=== Throughput Benchmark ===

Requests: 100000

I/O delay per request: 10ms

Platform Threads (200 thread pool):

Duration: 50.23s

Throughput: 1991 req/s

Virtual Threads:

Duration: 1.15s

Throughput: 86957 req/s

12.2. Memory Footprint

public class MemoryFootprintTest {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

Runtime runtime = Runtime.getRuntime();

System.out.println("=== Memory Footprint Test ===\n");

// Baseline

System.gc();

Thread.sleep(1000);

long baselineMemory = runtime.totalMemory() - runtime.freeMemory();

// Platform threads

testPlatformThreadMemory(runtime, baselineMemory);

// Virtual threads

testVirtualThreadMemory(runtime, baselineMemory);

}

private static void testPlatformThreadMemory(Runtime runtime, long baseline)

throws InterruptedException {

System.gc();

Thread.sleep(1000);

int numThreads = 1000;

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numThreads);

CountDownLatch startLatch = new CountDownLatch(1);

for (int i = 0; i < numThreads; i++) {

Thread thread = new Thread(() -> {

try {

startLatch.await();

Thread.sleep(10000); // Keep alive

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

});

thread.start();

}

Thread.sleep(1000);

long memoryWithThreads = runtime.totalMemory() - runtime.freeMemory();

long memoryPerThread = (memoryWithThreads - baseline) / numThreads;

System.out.println("Platform Threads (" + numThreads + " threads):");

System.out.println(" Total memory: " +

(memoryWithThreads - baseline) / (1024 * 1024) + " MB");

System.out.println(" Memory per thread: " +

memoryPerThread / 1024 + " KB\n");

startLatch.countDown();

latch.await();

}

private static void testVirtualThreadMemory(Runtime runtime, long baseline)

throws InterruptedException {

System.gc();

Thread.sleep(1000);

int numThreads = 100_000;

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(numThreads);

CountDownLatch startLatch = new CountDownLatch(1);

try (ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

for (int i = 0; i < numThreads; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

startLatch.await();

Thread.sleep(10000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

latch.countDown();

}

});

}

Thread.sleep(1000);

long memoryWithThreads = runtime.totalMemory() - runtime.freeMemory();

long memoryPerThread = (memoryWithThreads - baseline) / numThreads;

System.out.println("Virtual Threads (" + numThreads + " threads):");

System.out.println(" Total memory: " +

(memoryWithThreads - baseline) / (1024 * 1024) + " MB");

System.out.println(" Memory per thread: " +

memoryPerThread + " bytes\n");

startLatch.countDown();

latch.await();

}

}

}

13. Migration Guide

13.1. From ExecutorService to Virtual Threads

// Before: Platform thread pool

public class BeforeMigration {

private final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(100);

public void processRequests(List<Request> requests) {

for (Request request : requests) {

executor.submit(() -> handleRequest(request));

}

}

private void handleRequest(Request request) {

// Process request

}

record Request(String id) {}

}

// After: Virtual threads

public class AfterMigration {

private final ExecutorService executor =

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

public void processRequests(List<Request> requests) {

for (Request request : requests) {

executor.submit(() -> handleRequest(request));

}

}

private void handleRequest(Request request) {

// Same code, better scalability

}

record Request(String id) {}

}

13.2. From CompletableFuture to Structured Concurrency

// Before: CompletableFuture

public class CompletableFutureApproach {

public OrderSummary getOrderSummary(String orderId) {

CompletableFuture<Order> orderFuture =

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> fetchOrder(orderId));

CompletableFuture<Customer> customerFuture =

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> fetchCustomer(orderId));

CompletableFuture<List<Item>> itemsFuture =

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> fetchItems(orderId));

return CompletableFuture.allOf(orderFuture, customerFuture, itemsFuture)

.thenApply(v -> new OrderSummary(

orderFuture.join(),

customerFuture.join(),

itemsFuture.join()

))

.join();

}

private Order fetchOrder(String orderId) { return new Order(); }

private Customer fetchCustomer(String orderId) { return new Customer(); }

private List<Item> fetchItems(String orderId) { return List.of(); }

record Order() {}

record Customer() {}

record Item() {}

record OrderSummary(Order order, Customer customer, List<Item> items) {}

}

// After: Structured Concurrency

public class StructuredConcurrencyApproach {

public OrderSummary getOrderSummary(String orderId) throws Exception {

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

var orderTask = scope.fork(() -> fetchOrder(orderId));

var customerTask = scope.fork(() -> fetchCustomer(orderId));

var itemsTask = scope.fork(() -> fetchItems(orderId));

scope.join();

scope.throwIfFailed();

return new OrderSummary(

orderTask.get(),

customerTask.get(),

itemsTask.get()

);

}

}

private Order fetchOrder(String orderId) { return new Order(); }

private Customer fetchCustomer(String orderId) { return new Customer(); }

private List<Item> fetchItems(String orderId) { return List.of(); }

record Order() {}

record Customer() {}

record Item() {}

record OrderSummary(Order order, Customer customer, List<Item> items) {}

}

13.3. Gradual Migration Strategy

- Identify I/O Bound Code: Focus on services with blocking I/O

- Update Executor Services: Replace fixed thread pools with virtual thread executors

- Refactor Synchronized Blocks: In Java 21-24, replace with ReentrantLock; in Java 25+, keep as is

- Test Under Load: Ensure no regressions

- Monitor Pinning: Use JVM flags to detect remaining pinning issues

14. Conclusion

Virtual threads represent a fundamental shift in Java’s concurrency model. They bring the simplicity of synchronous programming to highly concurrent applications, enabling millions of concurrent operations without the resource constraints of platform threads.

Key Takeaways:

- Virtual threads are cheap: Create millions without memory concerns

- Blocking is fine: The JVM handles mount/unmount efficiently

- Java 25 solves pinning: Synchronized blocks no longer pin carrier threads

- Simple programming model: Write straightforward synchronous code that scales

- I/O bound workloads: Perfect for applications dominated by network or disk I/O

- Structured concurrency: Enables clean, maintainable concurrent code

When to Use Virtual Threads:

- High concurrency web servers

- Microservice communication

- Batch processing systems

- I/O intensive applications

- Database query processing

When to Use Platform Threads:

- CPU intensive computations

- Small number of long running tasks

- When you need precise control over thread scheduling

Virtual threads, combined with structured concurrency, provide Java developers with powerful tools to build scalable, maintainable concurrent applications without the complexity of reactive programming. With Java 25’s improvements eliminating the major pinning issues, virtual threads are now production ready for virtually any use case.