Firstly, let me acknowledge that there are lots of these kinds of posts on the internet. But the reason why i wrote this blog is that I wanted to force myself to consolidate the various articles I have read and my learnt knowledge in this space. I will probably update this article several times and I imagine I will do an IPV6 version of this in due course. That being said, on with the article…

If you have ever typed “what’s my IP address?” into Google and seen a number that looks nothing like the one shown in your laptop’s network settings, this article is for you. That number is not your computer. It is not your WiFi. It is not even really “you”.

It is simply the outermost return address used at the edge of the internet.

This article explains how this works using IPv4, the original and still most widely deployed version of the Internet Protocol. IPv6 solves many of these problems differently and deserves its own article.

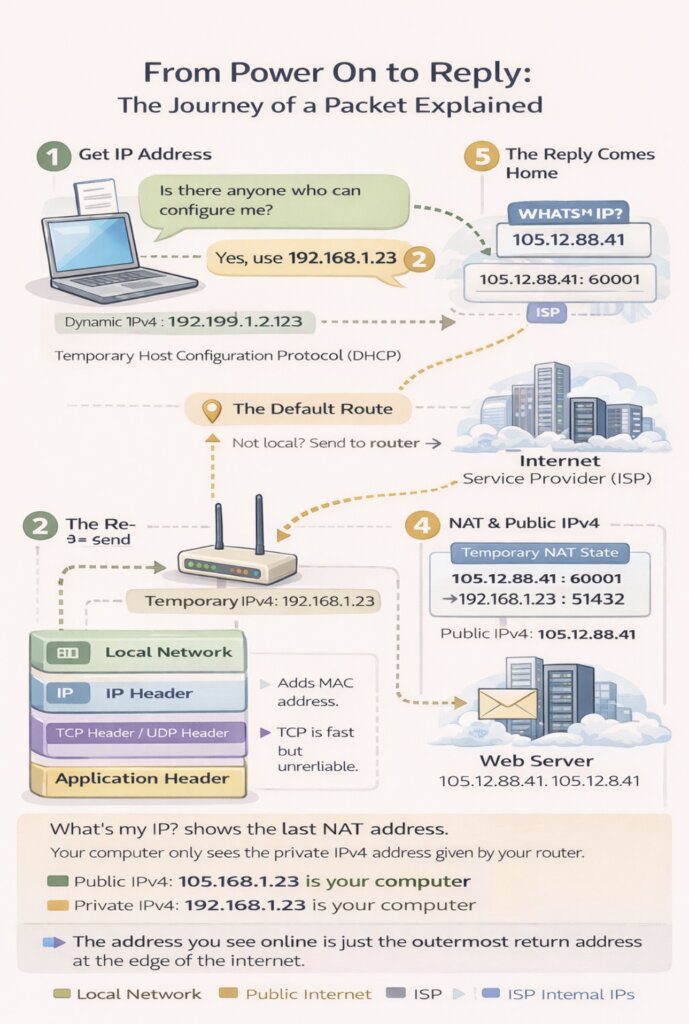

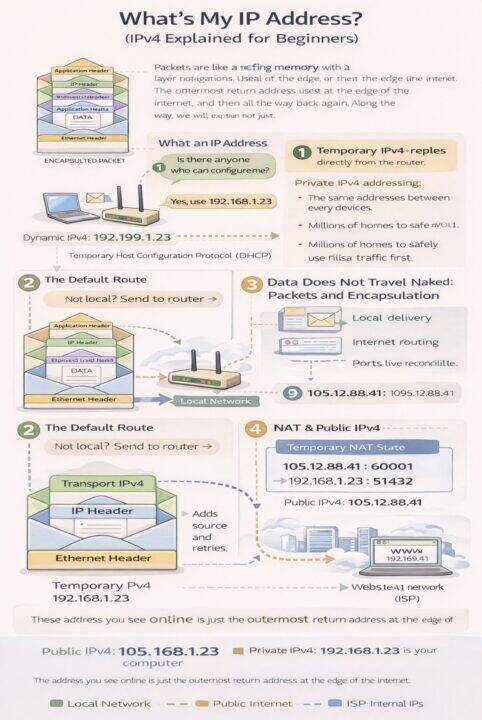

To understand IPv4, we need to follow a packet from the moment you turn your computer on, through your home network, across your ISP, into the internet, and then all the way back again. Along the way, we will explain not just what happens, but why it works this way.

1. What an IP Address Actually Is (IPv4)

An IPv4 address is a routing label. It answers one question only:

Where should replies be sent?

It is not an identity. It is not a person. It is not a permanent device identifier. It is simply an address written on the outside of a packet so routers know where to forward the response.

An IPv4 address is a 32 bit number, usually written as four numbers separated by dots, such as 192.168.1.23.

Your computer will use multiple IPv4 addresses during a single conversation, most of which you will never see.

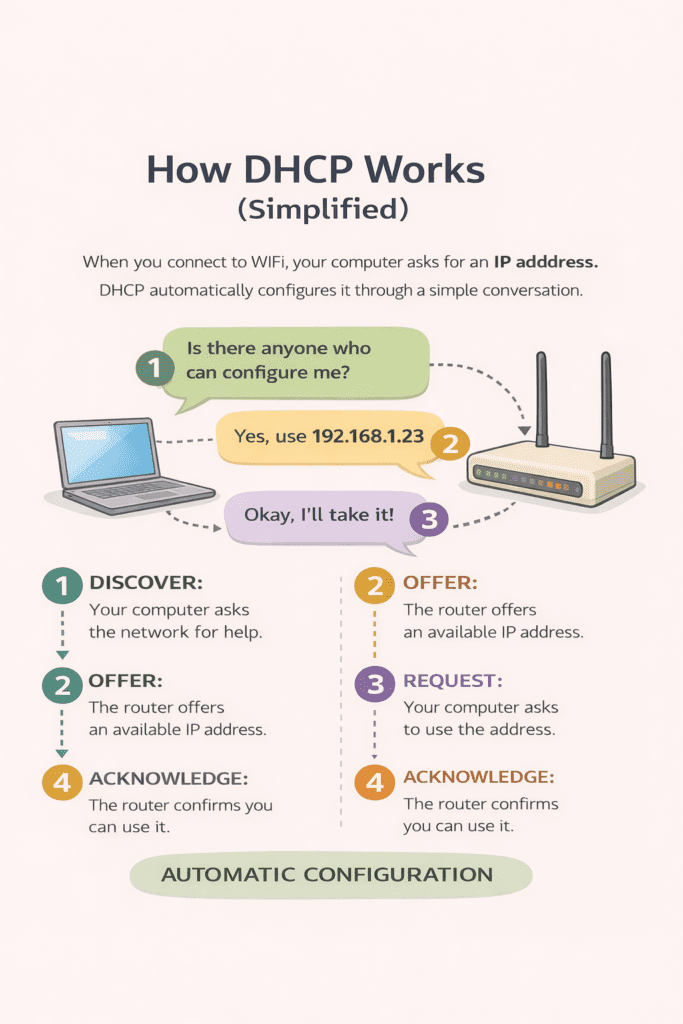

2. When You Turn Your Computer On: Getting an IPv4 Address (DHCP)

When your computer connects to a network, it starts with zero knowledge. It does not know:

- Its IPv4 address

- The router

- Where the internet is

So it asks.

This process is called DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol).

2.1 The DHCP Conversation (Simplified)

In plain language, the exchange looks like this:

- Your computer says: “Is there anyone who can configure me?”

- The router replies: “Yes, you can use this IPv4 address.”

- Your computer says: “I’ll take it.”

- The router replies: “You can keep it for a limited time.”

That limited time is called a lease. When the lease expires, the IPv4 address may change.

2.2 Why DHCP Exists

DHCP exists because manual configuration does not scale. It allows networks to:

- Automatically configure devices

- Avoid address conflicts

- Reuse IPv4 addresses efficiently

Without DHCP, home and enterprise networks would be brittle and error prone.

3. Why You Get a Private IPv4 Address (Not a Public One)

Your computer almost always receives a private IPv4 address, such as:

- 192.168.x.x

- 10.x.x.x

- 172.16.x.x to 172.31.x.x

This is a deliberate design decision in IPv4.

3.1 Reason 1: IPv4 Address Exhaustion

IPv4 supports about 4.3 billion public addresses. That sounded infinite in the 1980s. It is nowhere near enough today.

Every phone, laptop, tablet, TV, router, and device would need a public address. We ran out years ago.

Private IPv4 addressing allows:

- The same addresses to be reused everywhere

- Millions of homes to safely use

192.168.1.1at the same time - The internet to continue functioning without redesign

3.2 Reason 2: Safety by Default

Devices with private IPv4 addresses:

- Cannot be reached directly from the internet

- Are hidden behind a router or firewall

- Are protected unless they initiate traffic first

This creates a natural security boundary. Without private addressing, every device would need to behave like a hardened internet server.

3.3 Reason 3: Network Simplicity

Private IPv4 addressing allows:

- Homes to work without internet access

- Companies to redesign internal networks freely

- Devices to move between networks without reconfiguration

It decouples internal network design from the public internet.

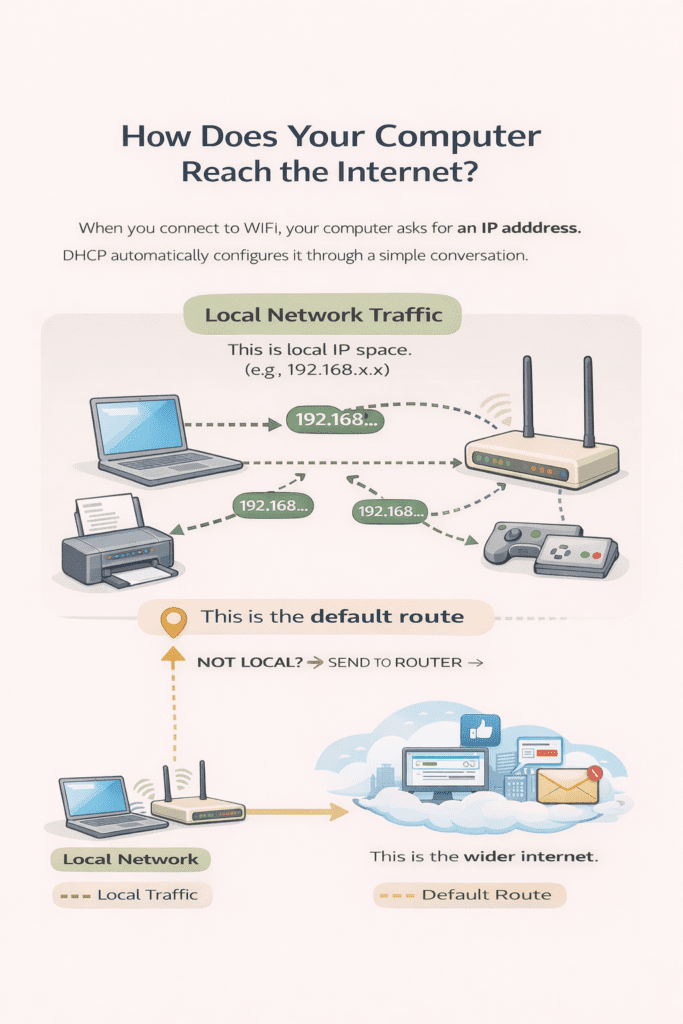

4. The Default Route : How Your Computer Decides Where to Send Traffic

When your computer wants to send data, the first thing it must decide is not how to send it, but where to send it.

Your computer cannot see the internet. It can only see:

- itself

- its local network

Everything else must be handed to another device for help.

This decision process is driven by something called the routing table.

4.1 The Routing Table (The Computer’s Decision List)

Every computer maintains a small list of rules called a routing table. Each rule answers a question of the form:

“If a packet is going to this kind of address, where should I send it next?”

The routing table usually contains at least two important entries:

- A rule for the local network

- A rule for everything else

4.2 How the Subnet Mask Defines “Local”

An IPv4 address on its own is not enough to decide where traffic should go. Your computer also needs to know which other IP addresses are considered part of the same local network.

That is the job of the subnet mask.

The subnet mask is a 32 bit number, just like an IPv4 address. It is usually written in dotted form, for example:

255.255.255.0

The subnet mask does not identify a device. Instead, it tells your computer which part of the IP address represents the network, and which part represents individual devices.

4.2.1 What the Subnet Mask Really Means

A subnet mask is a pattern of ones and zeros.

- A

1means “this bit belongs to the network” - A

0means “this bit belongs to the device”

For example:

IPv4 address: 192.168.1.23

Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

In binary, this looks like:

- IP address:

11000000.10101000.00000001.00010111 - Subnet mask:

11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000

This tells the computer:

- The first three numbers (

192.168.1) identify the network - The last number identifies individual devices on that network

4.2.2 A Different Subnet Mask Example

Subnet masks are not always 255.255.255.0. Larger or smaller networks use different masks to control how many devices are considered local.

For example:

IPv4 address: 10.0.5.42

Subnet mask: 255.255.0.0

This subnet mask means:

- The first two numbers (

10.0) identify the network - The last two numbers identify individual devices

With this configuration, your computer considers all of these addresses local:

10.0.1.110.0.99.20010.0.255.254

And it considers all of these addresses non local:

10.1.5.10192.168.1.134.216.8.10

So when sending traffic:

- Packets destined for

10.0.x.xare sent directly using Ethernet and ARP - Packets destined for anything else are sent to the router using the default route

This example shows that the subnet mask defines the boundary between “local” and “everything else”. Changing the mask changes that boundary, without changing how routing, ARP, or NAT fundamentally work.

4.2.2 How Your Computer Uses the Subnet Mask

When your computer wants to send a packet, it compares:

- Its own IP address

- The destination IP address

- The subnet mask

If the network portion of both addresses matches, the destination is considered local.

If the network portion does not match, the destination is considered non local.

For example, with:

- Your IP:

192.168.1.23 - Subnet mask:

255.255.255.0

These addresses are local:

192.168.1.1192.168.1.99192.168.1.254

These addresses are not local:

192.168.2.1010.0.0.534.216.8.10

4.2.3 Why This Decision Matters

If the destination is local:

- Your computer sends the packet directly using Ethernet

- ARP is used to discover the destination MAC address

- No router is involved

If the destination is not local:

- The routing table is consulted

- The default route is used

- The packet is sent to the router

This decision happens for every packet your computer sends.

4.2.4 Why Subnet Masks Exist at All

Subnet masks exist to give networks flexibility.

They allow:

- Small home networks

- Large enterprise networks

- Efficient use of IPv4 addresses

- Clear separation between local traffic and routed traffic

Without subnet masks, every device would either need to know about the entire internet or forward everything blindly to a router.

The subnet mask is what allows your computer to make a simple, fast, local decision about where traffic belongs.

4.2.5 The Key Mental Model

The subnet mask answers one question:

“Is this destination on my local network, or does it need to go to the router?”

That single decision determines how ARP works, when the default route is used, and whether NAT and CGNAT function correctly.

4.3 What the Default Route Actually Is

The default route is the rule that says:

“If no other rule matches, send the packet here.”

In almost all home and office networks, the default route points to the router (also called the default gateway).

In plain language, the default route means:

“If I don’t know how to reach this address directly, give the packet to the router and let it handle it.”

4.4 What Happens When You Access the Internet

When you visit a website:

- Your browser resolves the site name to an IPv4 address.

- Your computer checks whether that address is local.

- It is not.

- The routing table falls back to the default route.

- The packet is sent to the router.

At this point, your computer’s job is done. It does not know — and does not need to know — how the packet reaches the destination.

4.5 Why the Default Route Is Essential

Without a default route:

- Local networking still works

- The internet does not

Your computer would be able to talk to nearby devices, but any packet destined for an external address would have nowhere to go and would simply be dropped.

A missing or incorrect default route is one of the most common causes of “connected but no internet” problems.

4.6 Why This Matters for NAT and Everything That Follows

The default route is what ensures:

- All internet-bound traffic passes through the router

- The router sees outbound packets

- NAT can create state

- Replies can find their way back

Without a default route, NAT never happens, ARP is never triggered for the router, and return traffic becomes impossible.

The default route is the quiet rule that makes the internet reachable without your computer needing to understand the internet at all.

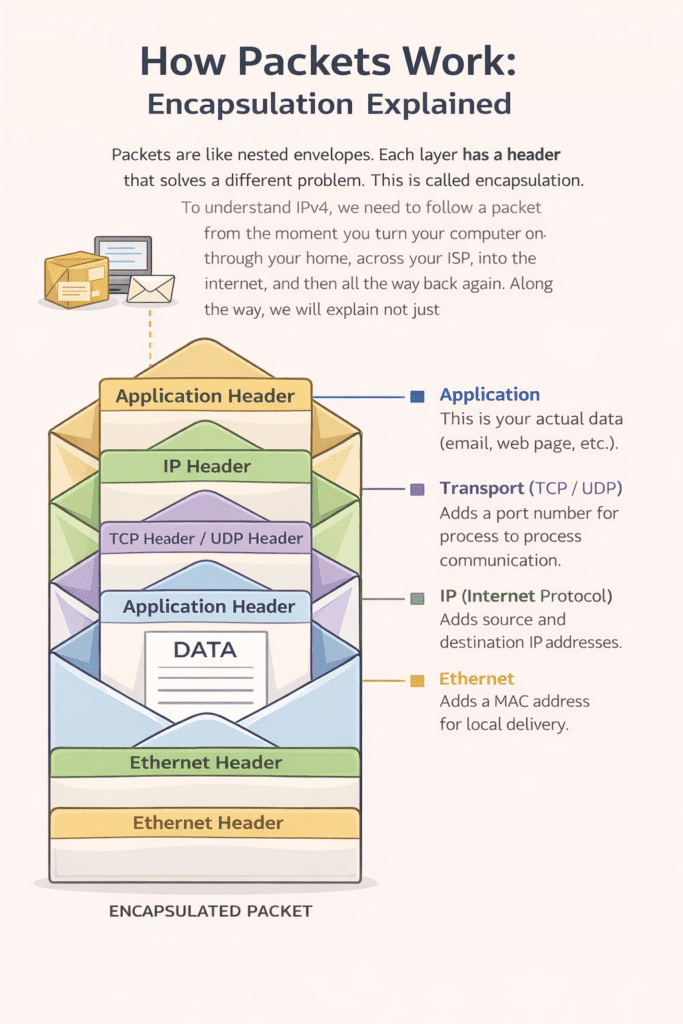

5. Data Does Not Travel Naked: Packets and Encapsulation

Your data does not travel as one continuous stream across the network.

Applications produce a stream of data, but before it is sent, the operating system breaks that stream into smaller units. Each unit is then wrapped with additional information in layers called headers, which tell the network how to deliver it.

This wrapping is called encapsulation. Each layer solves a different problem:

- Local delivery

- Internet routing

- Reliability

- Application meaning

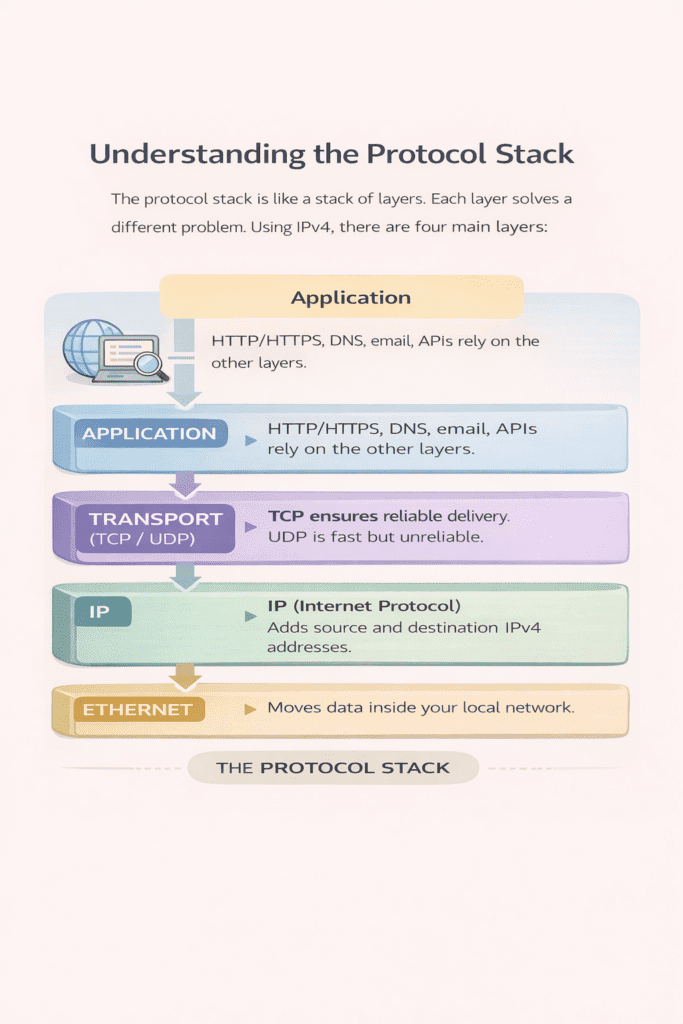

6. The Protocol Stack – What Each Layer Does (IPv4 Networks)

When your computer sends data across a network, it does not simply push bytes onto a wire. Applications produce data, but before that data leaves your device, the operating system passes it through a series of layers. Each layer adds information that helps the network move the data to the right place and deliver it to the right application.

A useful mental model is posting a letter. You write a message, put it in an envelope, add addressing information, and then hand it to a delivery system that moves it step by step toward its destination. Networking works the same way.

6.1 Ethernet – Local Delivery and MAC Address Resolution (Layer 2)

Ethernet moves packets between devices on the same local network, but it does not use IP addresses to do this. It uses MAC addresses, which are hardware identifiers assigned to network interfaces.

This raises an obvious question:

If applications and IP use IP addresses, how does Ethernet know which MAC address to send a packet to?

The answer is ARP.

6.1.1 Why MAC Addresses Exist

Ethernet operates only within a local network segment. It needs a way to deliver a packet to a specific physical device on that network. MAC addresses serve this purpose.

MAC addresses:

- Are used only on the local network

- Are not routable across the internet

- Change at every hop as a packet moves through routers

Routers strip off the Ethernet header and replace it at each hop.

6.1.2 The Problem Ethernet Needs to Solve

Your computer might want to send an IP packet to:

- Another device on the local network, or

- The router (default gateway)

In both cases, Ethernet must know the MAC address of the next device. But your computer usually only knows the IP address, not the MAC address.

6.1.3 How MAC Addresses Are Discovered (ARP)

ARP stands for Address Resolution Protocol. It translates IP addresses into MAC addresses on a local network.

Here is how it works step by step.

- Your computer checks its ARP cache

It first looks in a small local table to see if it already knows the MAC address for the destination IP. - If it does not know, it sends an ARP request

This request is broadcast to every device on the local network and says:

“Who has IP address X? Please tell me your MAC address.” - The correct device responds

The device that owns that IP address replies directly with its MAC address. - The mapping is cached

Your computer stores the IP to MAC mapping temporarily so it does not need to ask again.

This process usually takes milliseconds and is completely invisible to applications.

6.1.4 ARP in the Common Case (The Router)

Most of the time, your computer is not sending traffic to another local device. It is sending traffic to the internet.

In that case:

- The destination IP is not local

- The routing table says “send this to the default gateway”

- ARP is used to discover the MAC address of the router

- Ethernet delivers the packet to the router

The router then removes the Ethernet header, examines the IP packet, and repeats a similar process on the next network.

6.1.5 Why ARP Matters for Everything That Follows

ARP is the glue between Ethernet and IP.

Without ARP:

- IP packets could not be delivered on local networks

- The default route would be useless

- NAT would never see any traffic to translate

ARP is local, temporary, and constantly refreshed. It is one of the quiet background mechanisms that makes the rest of networking possible.

6.1.6 What Happens If Two Devices Respond to the Same ARP Request

Under normal conditions, only one device should ever respond to an ARP request. Each IPv4 address on a local network is supposed to be owned by exactly one device.

When two devices respond, it means something is wrong.

This situation is called an ARP conflict, and understanding it explains why ARP is simple but fragile.

The Normal ARP Assumption

ARP works because of one assumption:

For any given IPv4 address on a local network, there is exactly one MAC address.

ARP has:

- No authentication

- No verification

- No concept of “correct” ownership

It simply believes the last answer it hears.

What Actually Happens on the Wire

When your computer broadcasts an ARP request, it says:

“Who has IPv4 address 192.168.1.1? Tell me your MAC address.”

If two devices respond, this is what happens:

- Both devices send an ARP reply claiming ownership of the same IPv4 address.

- Your computer receives both replies.

- The ARP cache is updated with whichever reply arrives last.

There is no warning. No error. No negotiation.

The last response wins.

Why This Is Dangerous

Once the ARP cache is updated:

- All Ethernet traffic for that IPv4 address is sent to the MAC address stored in the cache

- Traffic intended for one device may go to another

- Packets may be silently dropped or intercepted

From the network’s point of view, nothing is “broken”. From the user’s point of view, things behave erratically.

Common Causes of Multiple ARP Replies

This situation usually occurs because of misconfiguration or failure:

- Two devices manually configured with the same IPv4 address

- A device joining a network with a stale configuration

- Virtual machines or containers cloned without changing IP settings

- Network failover systems briefly advertising the same address

- Misconfigured routers or bridges

In malicious scenarios, it can also be intentional.

ARP Spoofing and Poisoning

Because ARP trusts whoever answers, an attacker can exploit this.

An attacker can:

- Respond to ARP requests they do not own

- Convince devices that their MAC address owns another IP

- Intercept, modify, or drop traffic

This is known as ARP spoofing or ARP poisoning and is the basis for many local network attacks.

ARP itself has no defence against this.

How Operating Systems Try to Mitigate This

Modern operating systems do a few basic checks:

- They may log duplicate address warnings

- They may send additional ARP probes

- They may flush and relearn ARP entries

However, these are mitigations, not guarantees.

The protocol itself remains trusting by design.

Why ARP Was Designed This Way

ARP was designed in a simpler time:

- Local networks were trusted

- Devices were managed by a single administrator

- Performance and simplicity mattered more than security

ARP trades safety for speed and simplicity.

The Key Takeaway

ARP does not resolve conflicts.

ARP does not validate ownership.

ARP believes the last answer it hears.

When two devices respond to an ARP request, the network does not “decide who is right”. It simply follows the most recent information, even if that information is wrong.

This is why correct IP configuration matters, why ARP spoofing is possible, and why modern networks rely on additional controls to keep local traffic trustworthy.

6.2 IP (IPv4) – Addressing and Routing (Layer 3)

The Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4) is where IP addresses live.

IPv4 adds a source address and a destination address to each packet. Routers on the internet look only at the destination IPv4 address to decide where to forward the packet next. Each router moves the packet one step closer to its destination.

IPv4 does not guarantee delivery. It does not know whether a packet arrives, arrives twice, or arrives out of order. Its job is simply to try to move packets toward the correct destination.

IPv4 is the layer that NAT rewrites.

6.3 Transport Layer – TCP and UDP (Layer 4)

Once IPv4 has told the network where the packet should go, the transport layer tells the receiving system which conversation the packet belongs to.

This layer introduces ports.

Ports allow many applications on the same device to communicate at the same time using a single IPv4 address.

TCP and UDP are the two main transport protocols.

TCP breaks application data into packets, ensures they arrive in order, detects loss, and retransmits missing packets. This makes TCP reliable and suitable for web browsing and most application traffic.

UDP sends packets without guarantees. There is no retransmission and no ordering. This makes UDP faster and useful for real time traffic such as voice and video, where late data is no longer useful.

Ports live in the transport layer. NAT relies heavily on ports to distinguish between different connections that share the same public IPv4 address.

6.4 Application Layer – HTTP, HTTPS, DNS, Email and APIs

The application layer is where protocols that people recognise live.

This includes HTTP and HTTPS for websites, DNS for name lookups, email protocols, and application APIs. These protocols define what the data means and how applications should interpret it.

Applications assume that all lower layers will handle delivery, routing, and reliability. They do not care how many networks or routers are involved.

6.5 Why These Layers Matter Together

Each layer has a specific responsibility.

Ethernet handles local delivery.

IPv4 handles global addressing and routing.

The transport layer handles conversations and ports.

The application layer handles meaning.

Together, these layers ensure that data can be packaged correctly, routed across the internet, delivered back to the correct device, and handed to the correct application.

This layered model is essential to understanding NAT. NAT rewrites information in the IPv4 layer while preserving transport layer ports, and it depends on temporary state to map returning packets back to the correct internal device and application.

7. NAT Explained Properly (Why It Exists, How It Works, and the Types)

NAT exists because IPv4 ran out of addresses.

IPv4 only provides about 4.3 billion public addresses. That is not enough for every phone, laptop, tablet, and device to have one. Private IPv4 addressing solves part of the problem, but private addresses are not allowed on the public internet.

NAT is the mechanism that allows many private devices to share a small number of public IPv4 addresses while still receiving replies.

Without NAT, the modern IPv4 internet would not scale.

7.1 Why NAT Is Necessary

NAT exists for three reasons.

First, IPv4 address exhaustion. There simply are not enough public IPv4 addresses for every device.

Second, isolation and safety. Devices using private IPv4 addresses cannot be reached directly from the internet unless they initiate traffic. This provides a default security boundary.

Third, network independence. Homes and companies can design their internal networks freely without coordinating with the global internet.

NAT is not an optimisation. It is an IPv4 survival mechanism.

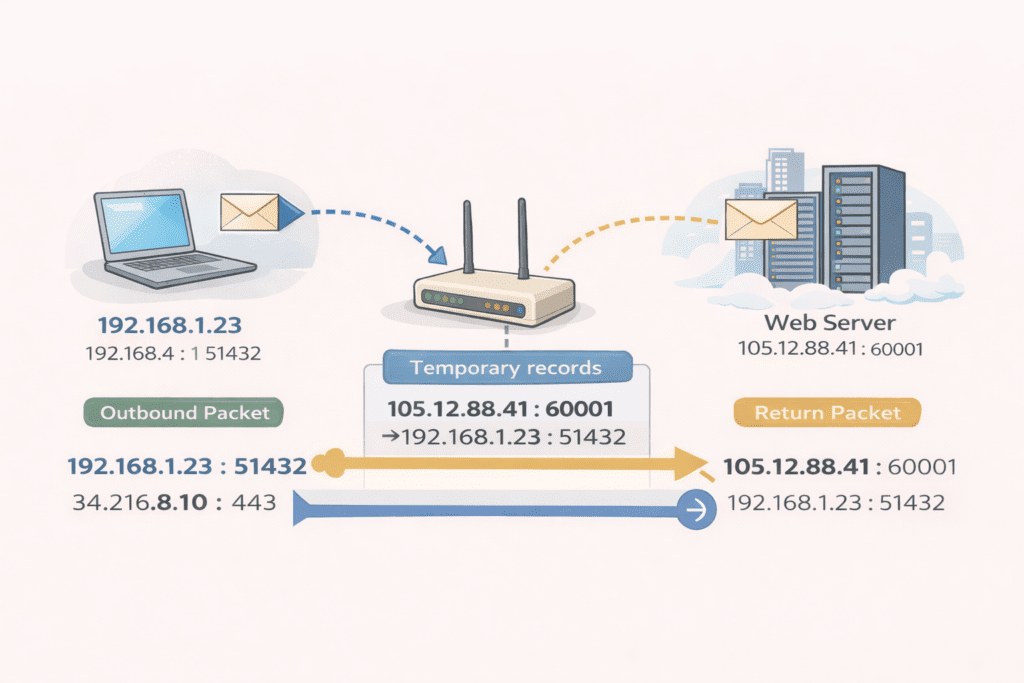

7.2 What NAT Actually Does

NAT does two things at the same time.

It rewrites addresses, and it remembers what it changed.

When your computer sends traffic to the internet, the NAT device:

- Replaces the private source IPv4 address with a public one

- Replaces the source port with a temporary public port

- Stores a temporary mapping that links the public address and port back to the private device and port

This temporary memory is called NAT state.

7.3 A Concrete Example

Your laptop sends a packet with:

- Source IPv4: 192.168.1.23

- Source port: 51432

- Destination IPv4: 34.216.8.10

- Destination port: 443

The NAT device rewrites it to:

- Source IPv4: 105.12.88.41

- Source port: 60001

At the same time, it records the following state:

105.12.88.41:60001 → 192.168.1.23:51432

Only the NAT device knows about this mapping.

7.4 How Replies Find the Right Device

The internet server replies to:

- Destination IPv4: 105.12.88.41

- Destination port: 60001

Because routing is based on destination address, the reply returns to the same NAT device. The NAT device:

- Looks up the destination port in its state table

- Rewrites the destination back to the private IPv4 address and port

- Forwards the packet to the correct internal device

Your laptop never sees the public address or the translation.

7.5 Why NAT Requires State

Multiple internal devices can talk to the same external service at the same time.

Ports are what keep these conversations separate.

Without the NAT state table, the NAT device would not know which internal device a reply belongs to. Guessing would mix traffic between users, so the only safe option is to drop unknown packets.

This is why NAT is stateful and why symmetric routing is required.

7.6 Common Types of NAT

There are several types of NAT in IPv4 networks.

Source NAT (SNAT)

This is the most common type. It rewrites the source IPv4 address and port for outbound traffic. Home routers and ISPs use this.

Destination NAT (DNAT)

This rewrites the destination IPv4 address and port. Port forwarding is a form of DNAT.

PAT (Port Address Translation)

This is what most people mean by NAT. Many private devices share a single public IPv4 address by using different ports.

Carrier Grade NAT (CGNAT)

This is NAT performed by ISPs. Your traffic may be translated once at home and again inside the ISP network.

All of these rely on temporary state.

7.7 The Key Thing to Remember About NAT

NAT is not routing.

NAT is not addressing.

NAT is temporary memory tied to a specific device.

Outbound traffic creates state.

Replies must return through the same device.

If the state is missing, the packet is dropped.

This is why NAT works — and why it fails in strange ways when routing becomes asymmetric.

8. How the Reply Finds Its Way Back

The server replies to the IPv4 address and port it was given.

Because routing is destination based, the reply naturally returns to the same NAT device. That device:

- Looks up the state entry

- Rewrites the destination back to the private IPv4 address

- Forwards the packet to your computer

Your computer never sees the translation.

9. Why NAT Must Be Symmetric

NAT state exists only on the device that created it.

9.1 Asymmetric Routing

If outbound traffic leaves through one NAT device but the reply comes back through another:

- The state is missing

- The destination port is meaningless

- The packet cannot be mapped

9.2 Why the Packet Is Dropped

The NAT device cannot guess. Guessing would mix traffic between users. The only safe option is to drop the packet.

This is allowed by IPv4 routing. It is disastrous for NAT.

10. What Happens When a Packet Is Dropped (And Why It Matters)

In the real world, packets often get dropped.

When we say a packet is “dropped,” it means a network device (like a router, NAT, firewall, or ISP gateway) received the packet but deliberately chose not to forward it any further. No error is sent back. No warning is logged on your screen. The packet simply disappears.

To understand this, you need to realise two things:

- Networks do not guarantee delivery — they try their best.

- Many devices on the path make independent decisions based on limited information.

10.1 Why Packets Get Dropped

There are several common reasons a packet can be dropped:

a. No matching NAT state exists

As explained earlier, NAT devices memorise outbound flows. If a return packet arrives and the NAT device has no entry for it (for example, due to asymmetric routing or expired state), it has no idea which internal device the packet belongs to — so the safest thing it can do is drop it.

b. TTL expires

Every IP packet has a Time To Live (TTL) counter. Each router along the path subtracts one from the TTL. If it reaches zero before reaching the destination, the packet is dropped to prevent infinite loops.

c. Congestion and buffer overflow

If a router’s buffers are full due to high traffic, it may drop packets to relieve congestion.

d. Firewalls and policy rules

Firewalls drop packets that violate security rules — for example, unsolicited incoming traffic with no matching session.

e. Broken or invalid packets

Packets with errors, invalid headers, or mismatched checksums are dropped to prevent corrupted data from propagating.

10.2 What Doesn’t Happen When a Packet Is Dropped

Contrary to what beginners often expect:

- You usually do not get an error message from the network telling you a packet was dropped.

- Your computer does not automatically know which packet was dropped or why.

- Intermediate routers do not resend dropped packets automatically.

This is fundamental: nothing magical happens at the network level when a packet is dropped — the network only forwards, not corrects.

10.3 How Higher-Level Protocols Respond

Different transport protocols respond differently when a packet disappears:

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)

TCP assumes a dropped or missing packet is a sign of network congestion or loss. It:

- Retransmits the missing data

- Slows down its sending rate

- Tries again until a timeout is reached

If enough packets are lost repeatedly, a TCP connection may stall or reset entirely.

UDP (User Datagram Protocol)

UDP simply sends packets. It has no built-in retry or error correction. If the packet is dropped, the data is gone. Applications using UDP must handle any loss themselves if they need reliability.

This is why streaming and real-time applications often use UDP — they can tolerate some loss and prefer lower latency — whereas web browsing and file transfers use TCP for reliability.

10.4 Why Packet Drops Feel Random to Users

Dropped packets are common. Networks are complex and dynamic. Some flows might succeed while other related ones fail, depending on:

- Which device drops the packet

- Timing of NAT state expiration

- Changes in routing paths

- Firewall rules that trigger intermittently

Because there is no explicit error message at the network level, the effects often look like:

- Web pages that never finish loading

- Videos that stall

- Online games that freeze or desync

- APIs that timeout sporadically

These symptoms feel random, because from the application’s point of view, the network simply stopped delivering expected data.

10.5 The Real Mental Model

The internet does not guarantee delivery of packets.

It tries to forward every packet based on current information and available state — and drops it silently if it cannot.

Understanding this makes sense of many common networking issues:

- Why your connection “hangs” instead of failing outright

- Why retransmissions are necessary

- Why VPNs and NAT traversal protocols exist

- Why sometimes a simple network reset fixes intermittent problems

Packet drops are not failures — they are normal behaviour in a best effort network.

11. Carrier Grade NAT (CGNAT)

So far, NAT has been explained in the context of your home router. Carrier Grade NAT (CGNAT) is the same idea applied at a much larger scale by internet service providers.

CGNAT exists because the global pool of public IPv4 addresses has been exhausted. There are simply not enough unique public IPv4 addresses for every home, phone, and device to have one. CGNAT allows ISPs to continue offering IPv4 connectivity by allowing many customers to share a small number of public addresses.

With CGNAT, your traffic is translated more than once. Your home router performs NAT first, and then the ISP performs NAT again inside its own network. Each translation layer keeps its own temporary state.

A typical CGNAT path looks like this:

Your laptop is assigned a private IPv4 address such as 192.168.1.23.

Your home router translates this to an address that looks public but is actually private to the ISP, often from a reserved range such as 100.64.0.0/10.

The ISP’s CGNAT device then translates that address again into a true public IPv4 address shared by many customers.

So a single connection may appear as:

Laptop: 192.168.1.23:51432

Home NAT: 100.64.12.8:55231

ISP CGNAT: 41.203.9.18:40012

When a server on the internet replies, the packet returns to the shared public IPv4 address and port. The ISP’s CGNAT device looks up its state table and forwards the packet back to your home router. Your home router then looks up its own state table and forwards the packet to the correct device and port inside your home.

This only works because both NAT layers see the outbound traffic first and because the return traffic flows back through the same devices in the same order. If either NAT layer does not have matching state, the packet is dropped.

CGNAT has practical consequences for end users. Inbound connections are usually impossible, because there is no stable public IPv4 address uniquely associated with your connection. Port forwarding at home often does not work, because the ISP’s NAT layer does not know how to reach you. Some peer to peer applications, online games, and diagnostics tools behave poorly or unpredictably under CGNAT.

CGNAT is not a design ideal. It is a pragmatic stopgap that allows IPv4 to keep working while the internet transitions toward IPv6. Understanding CGNAT explains why your public IP may change frequently, why hosting services from home is difficult, and why IPv4 networking often feels more complex than it should.

12. Why “What’s My IP” Sites Show Only One Address

Sites like Ipchicken only see the final public IPv4 address after all NAT layers.

They cannot see:

- Your private IPv4 address

- Your router’s internal address

- Your ISP’s internal network

Those addresses never leave their private domains.

13. The One Mental Model to Remember

IPv4 NAT is not routing.

IPv4 NAT is not magic.

IPv4 NAT is temporary memory tied to a specific device.

Outbound traffic creates memory.

Replies must return to the same device.

Different device means no memory.

No memory means dropped packets.

14. The Final Takeaway (IPv4)

You have a private IPv4 address because:

- The IPv4 internet cannot scale otherwise

- It is safer by default

- It simplifies network design

The public IPv4 address you see online is just the outermost return address at the edge of the internet.

IPv4 works not because packets are clever, but because routers and firewalls are disciplined accountants — and when the books do not balance, they quietly throw the transaction away.