Enterprise operating systems for servers, are not chosen because they are liked. They are chosen because they survive stress. At scale, an operating system stops being a piece of software and becomes an amplifier of either discipline or entropy. Every abstraction, compatibility promise, and hidden convenience eventually expresses itself under load, during failure, or in a security review that nobody budgeted for.

This is not a desktop comparison. This is about the ugly work at the backend of enterprise applications and systems – where uptime is contractual, reputational, security incidents are existential, and operational drag quietly compounds until the organisation slows without understanding why.

1. Philosophy: Who the Operating System Is Actually Built For

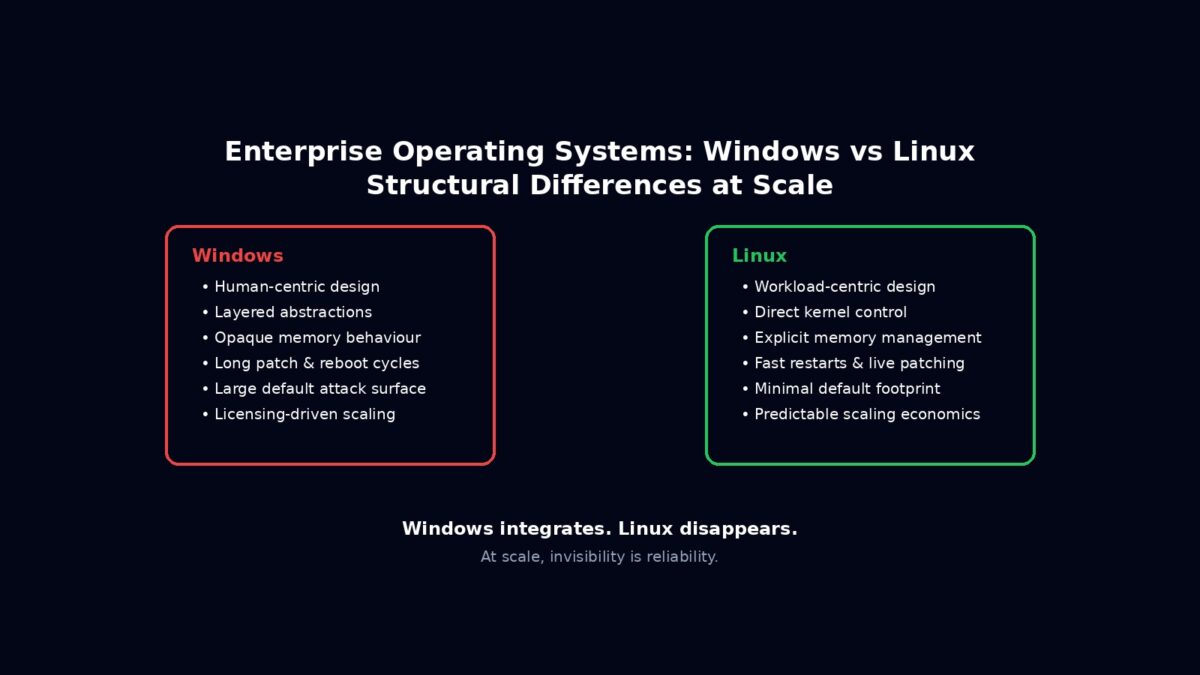

Windows was designed around people. Linux was designed around workloads.

That single distinction explains almost everything that follows. Windows prioritises interaction, compatibility, and continuity across decades of application assumptions. Linux prioritises explicit control, even when that control is sharp edged and unforgiving.

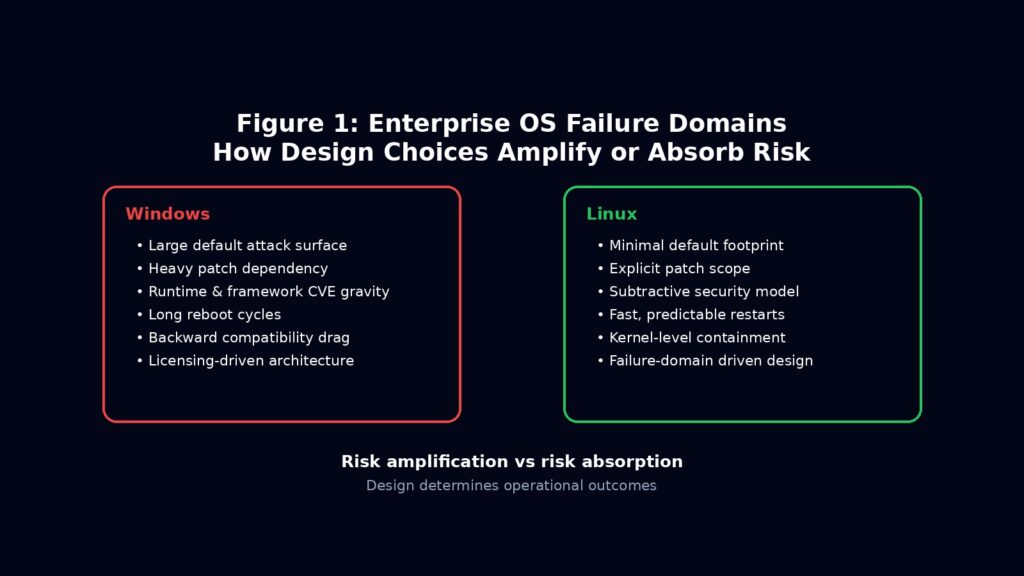

In an enterprise environment, friendliness is rarely free. Every convenience hides a decision that an operator did not explicitly make. Linux assumes competence and demands intent. Windows assumes ambiguity and tries to smooth it over. At scale, smoothing becomes interference.

2. Kernel Architecture: Determinism, Path Length, and Control

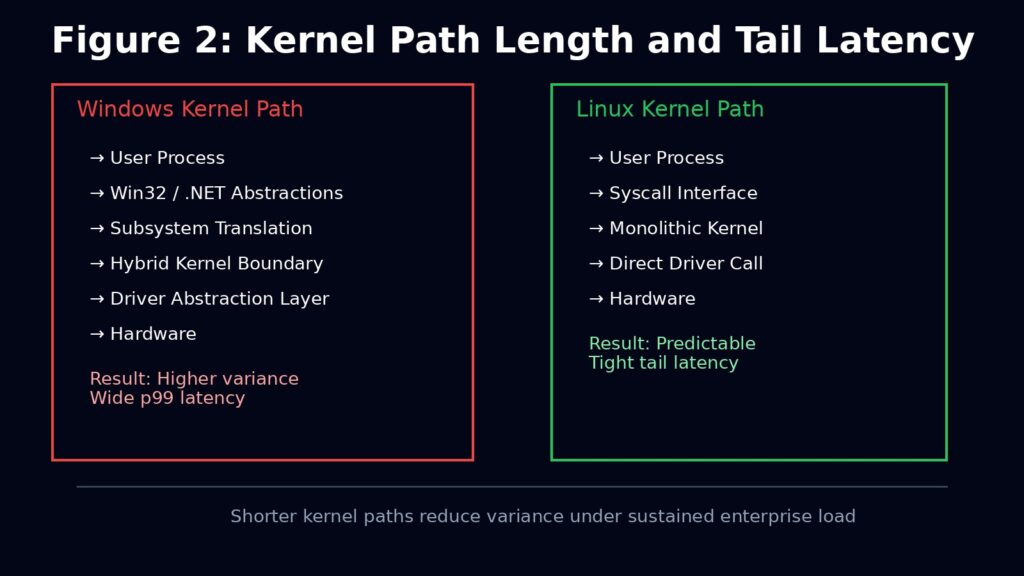

Linux uses a monolithic kernel with loadable modules, not because it is ideologically pure, but because it is fast, inspectable, and predictable. Critical subsystems such as scheduling, memory management, networking, and block IO live in kernel space and communicate with minimal indirection. When a packet arrives or a syscall executes, the path it takes through the system is short and largely knowable.

This matters because enterprise failures rarely come from obvious bottlenecks. They come from variance. When latency spikes, when throughput collapses, when jitter appears under sustained load, operators need to reason about cause and effect. Linux makes this possible because the kernel exposes its internals aggressively. Schedulers are tunable. Queues are visible. Locks are measurable. The system does very little “on your behalf” without telling you.

Windows uses a hybrid kernel architecture that blends monolithic and microkernel ideas. This enables flexibility, portability, and decades of backward compatibility. It also introduces more abstraction layers between hardware, kernel services, and user space. Under moderate load this works well. Under sustained load, it introduces variance that is hard to model and harder to eliminate.

The result is not lower average performance, but wider tail latency. In enterprise systems, tail latency is what breaks SLAs, overloads downstream systems, and triggers cascading failures. Linux kernels are routinely tuned for single purpose workloads precisely to collapse that variance. Windows kernels are generalised by design.

3. Memory Management: Explicit Scarcity Versus Deferred Reality

Linux treats memory as a scarce, contested resource that must be actively governed. Operators decide whether overcommit is allowed, how aggressively the page cache behaves, which workloads are protected, and which ones are expendable. NUMA placement, HugePages, and cgroup limits exist because memory pressure is expected, not exceptional.

When Linux runs out of memory, it makes a decision. That decision may be brutal, but it is explicit.

Windows abstracts memory pressure for as long as possible. Paging, trimming, and background heuristics attempt to preserve system responsiveness without surfacing the underlying scarcity. When pressure becomes unavoidable, intervention is often global rather than targeted. In dense enterprise environments this leads to cascading degradation rather than isolated failure.

Linux enables intentional oversubscription as an engineering strategy. Windows often experiences accidental oversubscription as an operational surprise.

4. Restart Time and the Physics of Recovery

Linux assumes restarts are normal. As a result, they are fast. Kernel updates, configuration changes, and service restarts are treated as routine events. Reboots measured in seconds are common. Live patching reduces the need for them even further.

Windows treats restarts as significant milestones. Updates are bundled, sequenced, narrated, and frequently require multiple reboots. Maintenance windows expand not because the change is risky, but because the platform is slow to settle.

Mean time to recovery is a hard physical constraint. When a system takes ten minutes to come back instead of ten seconds, failure domains grow even if the original fault was small.

5. Bloat as Operational Debt, Not Disk Consumption

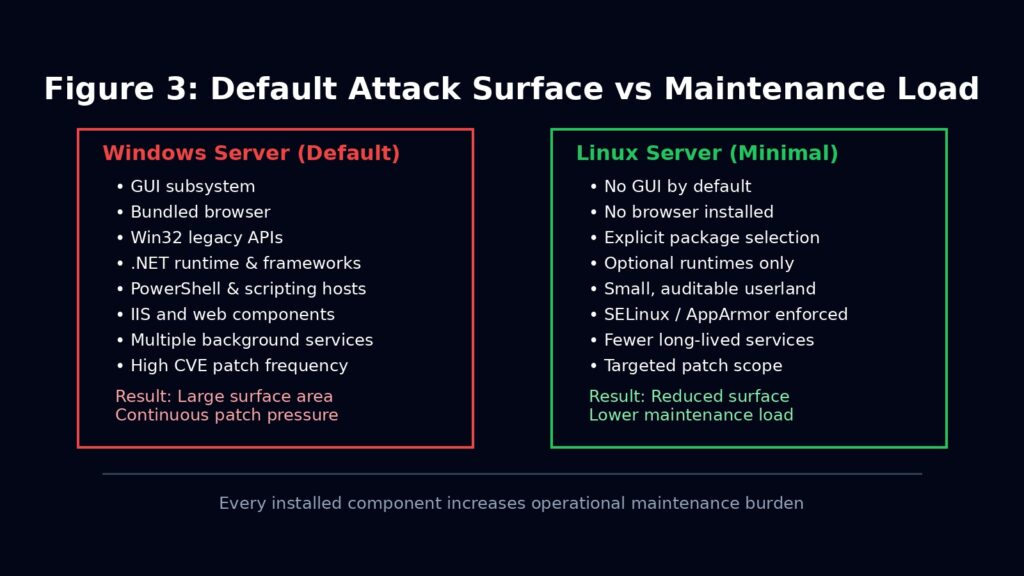

A Windows server often ships with a GUI, a browser, legacy subsystems, and optional features enabled by default. Each of these components must be patched, monitored, and defended whether they are used or not.

Linux distributions assume absence. You install what you need and nothing else. BusyBox demonstrates the extreme: one binary, dozens of capabilities, minimal surface area. This is not aesthetic minimalism. It is operational discipline.

Every unused component is latent liability. Linux is designed to minimise the number of things that exist.

6. Licensing Costs as a Systems Design Constraint

Linux licensing is deliberately dull. Costs scale predictably. Capacity planning is an engineering exercise, not a legal one.

Windows licensing scales with cores, editions, features, and access models. At small scale this is manageable. At large scale it starts influencing topology. Architects begin shaping systems around licensing thresholds rather than fault domains.

When licensing dictates architecture, reliability becomes secondary to compliance.

7. Networking, XDP, and eBPF: Policy at Line Rate

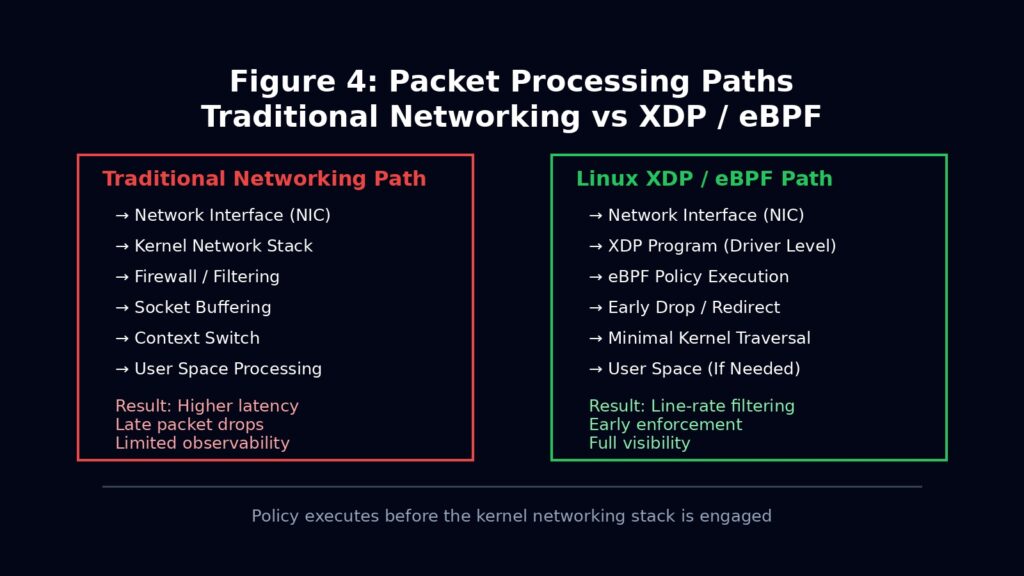

Linux treats the kernel as a programmable execution environment. With XDP and eBPF, packets can be inspected, redirected, or dropped before they meaningfully enter the networking stack. This allows DDoS mitigation, traffic shaping, observability, and enforcement at line rate.

This is not a performance optimisation. It is a relocation of control. Policy moves into the kernel. Infrastructure becomes introspective and reactive.

Windows networking is capable, but it does not expose equivalent in kernel programmability. As enterprises move toward zero trust, service meshes, and real time enforcement, Linux aligns naturally with those needs.

8. Containers as a Native Primitive, Not a Feature

Linux containers are not lightweight virtual machines. They are namespaces and control groups enforced by the kernel itself. This makes them predictable, cheap, and dense.

Windows containers exist, but they are heavier and less uniform. They rely on more layers and assumptions, which reduces density and increases operational variance.

Kubernetes did not emerge accidentally on Linux. It emerged because the primitives already existed.

9. Security Reality: Patch Gravity and Structural Exposure

Windows security is not weak because of negligence. It is fragile because of accumulated complexity.

A modern Windows enterprise stack requires constant patching across the operating system, the .NET runtime, PowerShell, IIS, legacy components kept alive for compatibility, and a long tail of bundled services that cannot easily be removed. Each layer brings its own CVEs, its own patch cadence, and its own regression risk. Patch cycles become continuous rather than episodic.

The .NET runtime is a prime example. It is powerful, expansive, and deeply embedded. It also requires frequent security updates that ripple through application stacks. Patching .NET is not a simple upgrade. It is a dependency exercise that demands testing across frameworks, libraries, and deployment pipelines.

Windows’ security model reflects its history as a general purpose platform. Backward compatibility is sacred. Legacy APIs persist. Optional components remain present even when unused. Security tooling becomes additive: agents layered on top of agents to compensate for surface area that cannot be removed.

Linux takes a subtractive approach. If a runtime is not installed, it cannot be exploited. Mandatory access controls such as SELinux and AppArmor constrain blast radius at the kernel level. Fewer components exist by default, which reduces the number of things that need constant attention.

Windows security is a campaign. Linux security is structural.

10. Stability as the Absence of Surprise

Linux systems often run for years not because they are neglected, but because updates rarely force disruption. Drivers, filesystems, and subsystems evolve quietly.

Windows stability has improved significantly, but its operational model still assumes periodic interruption. Reboots are expected. Downtime is normalised.

Enterprise stability is not about never failing. It is about failing in ways that are predictable, bounded, and quickly reversible.

Final Thought: Invisibility Is the Goal

Windows integrates. Linux disappears.

Windows participates in the system. Linux becomes the substrate beneath it. In enterprise environments, invisibility is not a weakness. It is the highest compliment.

If your operating system demands attention in production, it is already costing you more than you think. Linux is designed to avoid being noticed. Windows is designed to be experienced.

At scale, that philosophical difference becomes destiny.

Subject: On the “Numerology” of Estimation and the Path to Production

I’ve spent two decades in the trenches—from the era of physical racking to the current age of ephemeral serverless—and your piece isn’t just an observation; it’s a post-mortem of a thousand failed “Greenfield” projects.

You’ve touched on the “False Comfort of Numbers,” and it hits home. In my experience, the most dangerous artifact in a tech company isn’t a bug in production; it’s a high-fidelity Gantt chart for a discovery-phase project. It’s a document that systematically turns developers into liars and executives into gamblers.

A few reflections from the “War”:

The Entropy of “The Middle Game”: Your chess analogy is the most accurate description of mid-sprint discovery I’ve read. We often mistake complicated problems (which can be estimated) for complex ones (which must be navigated). Complexity is recursive; every “solved” dependency reveals three more that were previously invisible.

The Ethics of the “Risk Pack”: Moving from “Dates” to “Risk Packs” is the ultimate maturity test for a CTO. I’ve found that shipping a date is often a form of “organizational debt.” You gain temporary political capital today by borrowing against the team’s sanity and the product’s integrity six months from now.

Production as the Only Truth: “The system breathing in production” is the only metric that matters. I’ve seen teams spend months perfecting a “local” environment only to have the entire architecture collapse under the weight of real-world latency and security handshakes. If you aren’t failing in production by week two, you aren’t learning; you’re just fantasizing.

Decoupling as a Survival Strategy: Interdependencies are indeed the enemy. In 20 years, I’ve learned that if your architecture requires “synchronized shipping” between three different teams, you haven’t built a system; you’ve built a suicide pact.

Thank you for calling out the “theatre” of modern delivery. It’s time we stop treating software engineering like civil engineering. We aren’t building bridges over known rivers; we’re building bridges while discovering the laws of gravity.

Looking forward to more of your “Anti-Fiction” work.

What a stunning comment – thanks for taking the time! D|id you mean to put this comment on the Linux vs Windows article? Andrew