1. The Organisation That Optimised for Distrust

I once worked in a company with spectacularly low trust. Everything took ages (like years), quality was inconsistent (at best),costs were extraordinary and there was almost no common understanding of why things were so bad.

Clients were charged a small fortune for products that competitors could deliver at a fraction of the price. Internally, this was not seen as a signal of systemic dysfunction. Instead, leadership convinced itself that the real problem was staff dishonesty.

People were not struggling. They were lying. Or so the story went.

2. When Control Becomes the Strategy

Once you believe the problem is dishonesty, the solution seems obvious: control harder.

The organisation began contracting everyone into their commitments. Meetings stopped being places where ambiguity could be explored and became legal style discovery exercises. One leader even started recording meetings, as if future playback would somehow convert uncertainty into accountability.

Timesheets followed. Surely if every minute was captured and categorised, delivery would improve. When that failed, internal cross charging arrived. Entire teams were hired whose sole job was to recharge teams to other teams, under the belief that the tension of accepting internal charges would force discipline and performance.

None of this worked.

The only measurable outcome was a larger organisation with more friction, more defensiveness and more arguments. Energy moved away from delivery and toward self protection and tribalism.

3. Micro Management and the Hidden Tax on Delivery

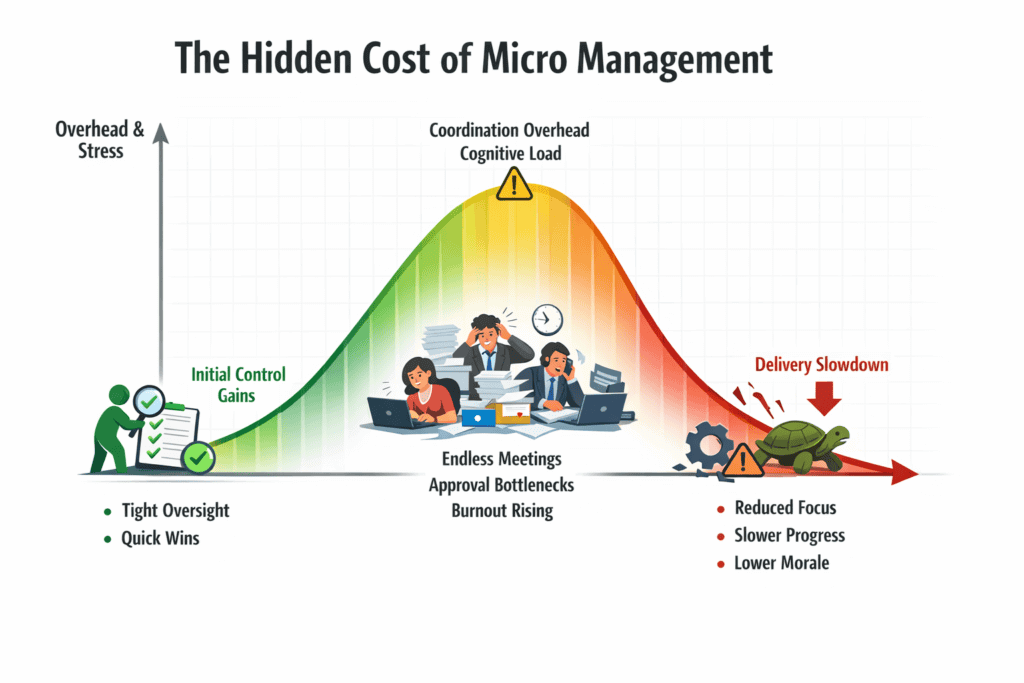

What leaders consistently underestimate is the overhead of micro management.

Every additional approval step slows flow.

Every forced status update steals time from real work. Every justification meeting teaches people to optimise for optics, not outcomes.

Micro management does not just consume time, it fragments attention. Engineers stop thinking in systems and start thinking in inboxes. Teams stop solving problems and start preemptively defending themselves against future blame.

The most damaging part is that micro management creates the illusion of control while actively degrading capability. The people closest to the work lose autonomy. The people farthest from the work gain dashboards. And everyone feels busy.

Low trust organisations never account for this tax. They measure utilisation. They measure hours. They never measure how much thinking capacity they have destroyed.

4. Naval Gazing Disguised as Rigor

The result is a culture of permanent explanation.

Every delay requires a post mortem.

Every miss spawns a deck.

Every deck spawns more meetings.

This is not rigor. It is naval gazing. It is the organisation staring at itself instead of the problem it exists to solve.

In these environments, explanation replaces progress. And explanation without progress looks indistinguishable from excuse making.

Trust does not increase. It decays.

5. The Counterintuitive Reality of Trust

Here is the uncomfortable truth leaders eventually discover, usually too late.

Trust on projects nobody understands gets built through demonstrated competence in small increments, not through explanation.

The instinct is always to educate stakeholders until they understand enough to trust the work. This rarely succeeds. Complex technology resists compression into executive summaries. Attempts to do so either oversimplify to the point of dishonesty or overwhelm people into silent nodding.

Worse, explanation without delivery erodes credibility.

6. Deliver Something Tangible, Early

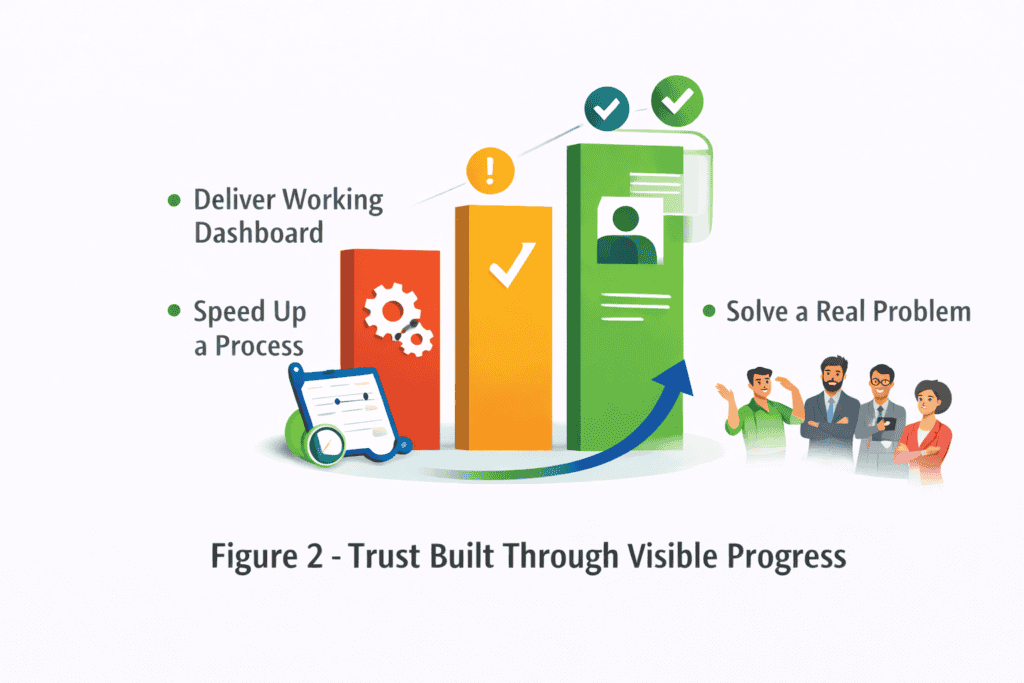

The fastest way to build trust is to ship something real.

Not a proof of concept only engineers can appreciate. Something visible. Something that solves a real problem, however small. A dashboard that now exists. A process that now completes in minutes instead of days.

People will happily say “I don’t understand how it works” as long as they can also say “but I can see that it does”.

7. Create Proxy Metrics People Can Track

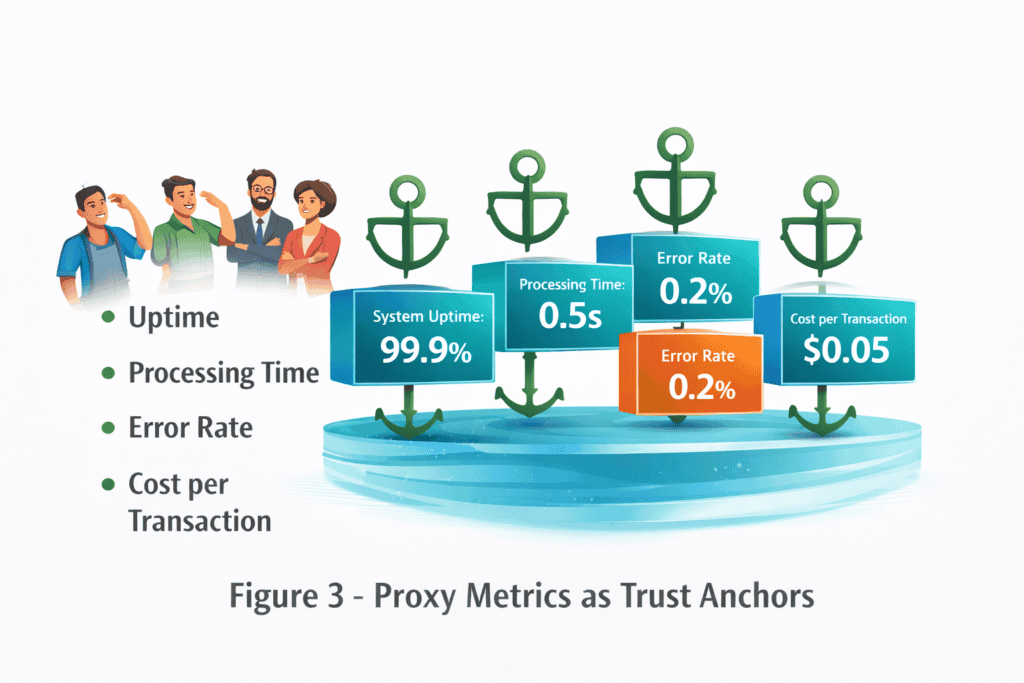

If stakeholders cannot evaluate the technical work directly, give them metrics they can understand.

Uptime.

Latency.

Error rates.

Cost per transaction.

These become trust anchors. They allow leaders to observe improvement without needing to understand the machinery underneath. Over time, the metrics speak for the team.

8. Be Predictable Where It Counts

Predictability is deeply underrated.

Status updates at the same time every week.

Budgets that do not surprise.

Risks surfaced early, not theatrically late.

When the visible parts of a project are calm and disciplined, people extend trust to the invisible technical work. Chaos in communication destroys confidence even when the engineering is sound.

9. Find a Trusted Translator

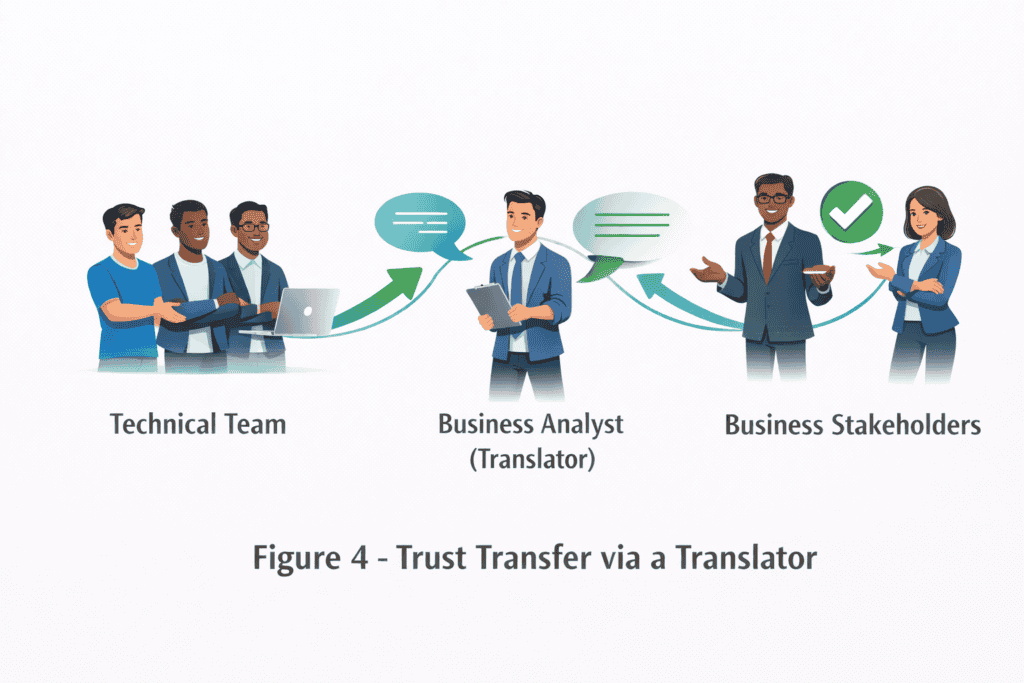

Trust often flows through people, not artefacts. A technically literate but business fluent individual can act as a bridge. A product owner. A business analyst. A respected engineering lead. Their confidence becomes transferable. Stakeholders who trust them begin to trust the team by proxy. This is not politics. It is how humans reduce uncertainty.

10. How High Trust Organisations Actually Operate (And Why This Feels Uncomfortable)

This is the part that tends to shock people who have spent years inside low trust organisations.

High trust organisations do not look more controlled.

They look dangerously loose.

There are fewer approvals, not more.

Fewer meetings, not more.

Less documentation, not less accountability.

From the outside, they can appear reckless. From the inside, they feel calm.

Failure Is Not a Scandal

In low trust organisations, failure is treated like a crime scene. Access is restricted. Statements are taken. Timelines are reconstructed. The goal is to find who caused the problem, because blame is the only available control mechanism.

In high trust organisations, failure is treated like telemetry.

Something happened. That means the system just told us something useful.

The first questions are not “who approved this?” or “why did you say it would work?” They are “what broke?”, “what signal did we miss?”, and “how do we make sure this class of failure cannot happen again?”

This is why post incident reviews in high trust environments feel almost unsettling to newcomers. They are calm. Factual. Almost boring. Nobody is performing. Nobody is defending themselves. There is nothing to defend.

It Is Still a Commercial Organisation

High trust does not mean naive.

These organisations are still commercial entities with customers, margins and obligations. Repeated failure, negligence or consistently poor judgment is not ignored, and it is not endlessly tolerated. The difference is how it is handled.

Patterns of behaviour are addressed deliberately and discretely. Conversations happen early, in private, and with clarity. Expectations are restated. Support is offered where it makes sense. When change does not occur, decisions are made without theatre, public shaming or moral grandstanding.

Accountability is real, but it is exercised with dignity.

This is intentional. Public punishment erodes trust far beyond the individual involved. Quiet, decisive action preserves the integrity of the system while protecting everyone else’s ability to operate without fear.

Accountability Is Structural, Not Personal

Low trust organisations believe accountability comes from pressure. High trust organisations know it comes from design.

Clear ownership exists, but it is paired with real authority. Teams are accountable for outcomes they can actually influence. When something fails outside their control, the organisation fixes the interface, not the person.

People are not asked to commit to certainty they do not possess. They are asked to commit to discovery, transparency and response. This removes the incentive to lie.

Failure Is Paid for Once

Low trust organisations pay for failure repeatedly.

They pay in meetings.

They pay in reporting.

They pay in re approval cycles.

They pay in talent attrition.

High trust organisations pay for failure once, by fixing the underlying mechanism that allowed it to occur.

A bad deploy does not result in more approval gates. It results in better automated checks. An outage does not result in stricter sign off. It results in improved isolation, better fallbacks and clearer operational metrics.

The system gets stronger. The people are left intact.

You Are Trusted Until You Prove Otherwise

This is the hardest concept for people coming from low trust environments to internalise.

In high trust organisations, trust is the default state.

People are assumed to be competent and acting in good faith. Controls are added only where evidence shows they are needed. And when trust is violated, the response is precise and local, not systemic and punitive.

One failure does not collapse trust in the entire organisation.

The Real Source of the Shock

The real shock is not how failures are handled. The shock is realising how much energy low trust organisations waste trying to prevent embarrassment rather than improving capability. How much human creativity is sacrificed in the name of control. How many smart people are trained to explain instead of build.

Once you see how a high trust organisation operates, it becomes impossible to unsee the dysfunction.

11. Admit Uncertainty Without Flinching

False certainty is one of the fastest ways to destroy trust.

Saying “we don’t know yet” followed by “here is how we will find out” builds far more confidence than over confident predictions that later collapse. People forgive uncertainty. They do not forgive being misled.

Honesty about unknowns is a trust accelerant.

12. What Stakeholders Are Really Asking

At its core, this was never about technology. Trust on these projects is trust in people.

Stakeholders are asking whether you will tell them early when things go wrong. Whether you will protect their interests when they cannot protect themselves. Whether your judgment is sound even when they cannot personally verify the details.

Low trust organisations try to replace these questions with process, surveillance and contracts. High trust teams answer them through behaviour. And this is the uncomfortable conclusion.

When trust is missing, organisations reach for control. When trust is present, control becomes almost unnecessary. Confusing control with delivery feels safe. But it is one of the most reliable ways to ensure you get neither.

Ultimately, trust is built through demonstrated competence, not control.