Why More Information Doesn’t Mean More Understanding

We’ve all heard the mantra: data is the new oil. It’s become the rallying cry of digital transformation programmes, investor pitches, and boardroom strategy sessions. But here’s what nobody mentions when they trot out that tired metaphor: oil stinks. It’s toxic. It’s extraordinarily difficult to extract. It requires massive infrastructure, specialised expertise, and relentless refinement before it becomes anything remotely useful. And even then, used carelessly, it poisons everything it touches.

The comparison is more apt than the evangelists realise.

1. The Great Deception

Somewhere along the way, we convinced ourselves that accumulating information was synonymous with gaining understanding. That if we could just capture enough data points, build enough dashboards, and train enough models, clarity would emerge from the chaos. This is perhaps the most dangerous illusion of the modern enterprise.

I’ve watched organisations drown in their own data lakes, though calling them lakes is generous. Most are swamps. Murky, poorly mapped, filled with debris from abandoned projects and undocumented schema changes. Petabytes of customer interactions, transaction logs, sensor readings, and behavioural metrics, all meticulously captured, haphazardly catalogued, and largely ignored. The dashboards multiply. The reports proliferate. And yet the fundamental questions remain unanswered: What should we do? Why are we doing it? What does success actually look like?

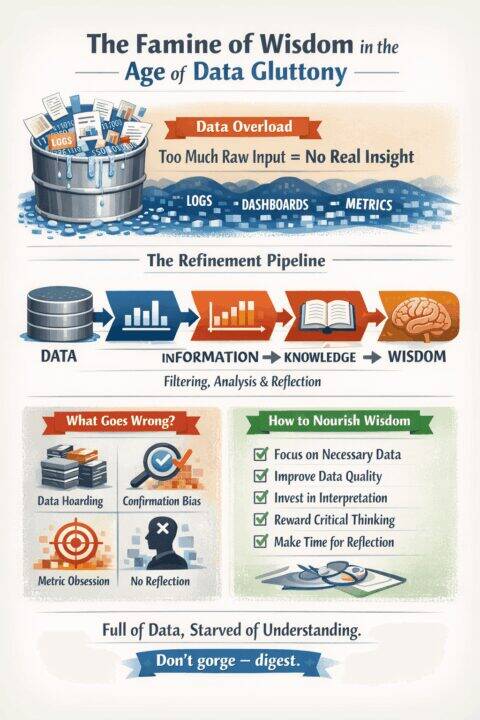

Information is not knowledge. Knowledge is not wisdom. And wisdom is not guaranteed by any quantity of the preceding.

2. The Refinement Problem

Crude oil, freshly extracted, is nearly useless. It must be transported, heated, distilled, treated, and transformed through dozens of processes before it becomes the fuel that powers anything. Each step requires expertise, infrastructure, and enormous capital investment. Skip any step, and you’re left with toxic sludge.

Data follows the same brutal economics. Raw data is not an asset. It’s a liability. It costs money to store, creates security and privacy risks, and generates precisely zero value until someone with genuine expertise transforms it into something actionable. Yet organisations hoard data like digital dragons sitting on mountains of gold, convinced that possession equals wealth.

The transformation from data to wisdom requires multiple refinement stages: Data must become information through structure and context. Information must become knowledge through analysis and interpretation. Knowledge must become wisdom through experience, judgement, and critically, self awareness. Each transition demands different skills, different tools, and different kinds of thinking. Most organisations have invested heavily in the first transition and almost nothing in the rest.

3. Tortured Data Will Confess Anything

There’s an old saying among statisticians: torture the data long enough and it will confess to anything. This isn’t a joke. It’s a warning that most organisations have failed to heed.

With enough variables, enough segmentation, and enough creative reframing, you can make data support almost any conclusion you’ve already decided upon. This is the dark side of sophisticated analytics: the tools that should illuminate truth become instruments of confirmation bias. The analyst who brings inconvenient findings gets asked to “look at it differently.” The dashboard that shows declining performance gets redesigned to highlight a more flattering metric. The model that contradicts the executive’s intuition gets retrained until it agrees.

If the data is telling you something that seems wrong, there are two possibilities. The first is that you’ve discovered a genuine insight that challenges your assumptions. This is rare and valuable. The second, far more common, is that something in your data pipeline is broken: bad joins, stale caches, misunderstood definitions, silent failures in upstream systems. Always validate. Always check your assumptions. And be deeply suspicious of any analysis that confirms exactly what you hoped it would.

4. Embedded Lies

Here’s something that keeps me up at night: data doesn’t just contain errors. It contains embedded lies. Not malicious lies, necessarily, but structural deceits built into the very fabric of what we choose to measure and how we measure it.

Consider fraud in financial services. Industry estimates suggest that only around 8% of fraud is actually reported. That means any organisation fixating on reported fraud metrics is studying the tip of an iceberg while congratulating themselves on their visibility. The dashboards look impressive. The trend lines might even be heading in the right direction. But you’re optimising for a shadow of reality.

The organisation that achieves genuine wisdom doesn’t ask “how much fraud was reported last quarter?” It asks questions like: “Who else paid money into accounts we now know were fraudulent but never reported it? What patterns preceded the fraud we caught, and where else do those patterns appear? What are we not seeing, and why?”

These questions are harder. They require linking disparate data sources, challenging comfortable assumptions, and accepting that your metrics have been lying to you. Not because anyone intended deception, but because the data only ever captured what was convenient to capture. The fraud that gets reported is the fraud that was easy to detect. The fraud that doesn’t get reported is, almost by definition, the sophisticated fraud you should actually be worried about.

5. The Illusion of Knowing Ourselves

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable. The data obsession isn’t just an organisational failure. It’s a mirror reflecting a deeper human delusion. We believe we are rational agents making deliberate, informed decisions. Neuroscience and behavioural economics have spent decades demolishing this comfortable fiction.

We are pattern matching machines running on heuristics, rationalising decisions we’ve already made unconsciously. We seek information that confirms what we already believe. We mistake correlation for causation. We see patterns in noise and miss signals in data. We are spectacularly bad at understanding our own motivations, biases, and blind spots.

This matters because organisations are collections of humans, and they inherit all our cognitive limitations while adding a few of their own. When an executive demands “more data” before making a decision, they’re often not seeking understanding. They’re seeking comfort. The data becomes a security blanket, a way to defer responsibility, a defence against future criticism. “The data told us to do it.”

But the data never tells us to do anything. We tell ourselves stories about what the data means, filtered through our assumptions, our incentives, and our fears. Without self knowledge, without understanding our own biases and limitations, more data simply gives us more raw material for self deception.

6. The Famine Amidst Plenty

We are living through a peculiar paradox: a famine of wisdom amidst a gluttony of data. We have more information than any civilisation in history and arguably less capacity to make sense of it. The problem isn’t access. It’s digestion.

Consider how we’ve changed the way we consume information. Twenty years ago, reading a book or a longform article was normal. Today, we scroll through endless feeds, consuming fragments, never staying with any idea long enough to truly understand it. We’ve optimised for breadth at the expense of depth, for novelty at the expense of comprehension, for reaction at the expense of reflection.

Organisations have mirrored this dysfunction. The average executive receives hundreds of emails daily, sits through back to back meetings, and is expected to make consequential decisions in the gaps between. They have access to realtime dashboards showing every conceivable metric, yet they lack the time and mental space to think deeply about any of them. The tyranny of the urgent crowds out the importance of the significant.

Wisdom requires time. It requires sitting with uncertainty. It requires the humility to admit what we don’t know and the patience to discover it properly. None of these things scale. None of them show up on a dashboard. None of them impress investors or boards.

7. What Organisations Should Actually Do

If data is indeed the new oil, then we need to think like refineries, not like hoarders. This means fundamental changes in how we approach information.

First, ruthlessly prioritise. Not all data deserves collection, storage, or analysis. The question isn’t “can we capture this?” but “does this help us make better decisions about things that actually matter?” Most organisations would benefit from capturing less data, not more, but capturing the right data with much greater intentionality.

Second, drain the swamp before building the lake. If you can’t trust your existing data, adding more won’t help. Invest in data quality, in clear ownership, in documentation that actually gets maintained. A small, clean, well understood dataset is infinitely more valuable than a vast murky swamp where nobody knows what’s true.

Third, invest in the refinement stages. For every pound spent on data infrastructure, organisations should be spending at least as much on the human capabilities to interpret it: skilled analysts, yes, but also domain experts who understand context, and experienced leaders who can exercise judgement. The bottleneck is rarely data. It’s the capacity to transform data into actionable understanding.

Fourth, build validation into everything. Assume your data is lying to you until proven otherwise. Cross reference. Sanity check. Ask “what would have to be true for this number to be correct?” and then verify those preconditions. Create a culture where questioning data is rewarded, not punished.

Fifth, ask the questions your data can’t answer. The most important insights often live in the gaps. What aren’t you measuring? What can’t you see? If only 8% of fraud is reported, what does the other 92% look like? These questions require imagination and domain expertise, not just better analytics.

Sixth, create space for reflection. Wisdom doesn’t emerge from realtime dashboards or daily standups. It emerges from stepping back, asking deeper questions, and allowing insights to crystallise over time. This is profoundly countercultural in most organisations, which reward visible activity over invisible thinking. But the most consequential decisions (strategy, culture, longterm investments) require exactly this kind of slow, deliberate cognition.

Seventh, institutionalise self awareness. This might sound soft, but it’s absolutely critical. Decisions made from a place of self knowledge, understanding why we want what we want, recognising our biases, acknowledging our blind spots, are categorically different from decisions made in ignorance of our own psychology. Build in mechanisms that surface assumptions, challenge groupthink, and create psychological safety for dissent.

Eighth, measure what matters. The easiest things to measure are rarely the most important. Clicks are easier to count than customer trust. Output is easier to measure than outcomes. Activity is easier to track than impact. The discipline of identifying what actually matters, and accepting that some of it may resist quantification, is essential to breaking free from data theatre.

8. Decisions From a Place of Knowing

The goal isn’t to reject data. That would be as foolish as rejecting evidence. The goal is to put data in its proper place: as one input among many, useful but not sufficient, informative but not determinative.

The best decisions I’ve witnessed, the ones that created genuine value, that navigated genuine uncertainty, that proved robust in the face of changing circumstances, didn’t come from better dashboards. They came from leaders who understood themselves well enough to know when they were rationalising versus reasoning, who had cultivated judgement through experience and reflection, and who treated data as a conversation partner rather than an oracle.

This kind of wisdom is slow to develop and impossible to automate. It requires exactly the kind of patient, deep work that our information saturated environment makes increasingly difficult. But it remains the essential ingredient that separates organisations that thrive from those that merely survive.

9. Conclusion: From Gluttony to Nourishment

Data is indeed the new oil. Which means it’s messy, it’s dangerous, and in its raw form, it’s nearly useless. It stinks. It requires enormous effort to extract. It demands sophisticated infrastructure and genuine expertise to refine. And like oil, its careless use creates pollution: in this case, pollution of our decisionmaking, our organisations, and our understanding of ourselves.

The organisations that will win the next decade aren’t the ones with the biggest data lakes, or swamps. They’re not the ones with the fanciest analytics platforms or the most impressive dashboards. They’re the ones that recognise the difference between information and understanding, between metrics and meaning, between data and wisdom.

They’ll be the organisations that ask hard questions about what their data isn’t showing them. That validate relentlessly rather than trust blindly. That understand tortured data will confess to anything and refuse to torture it. That recognise the embedded lies in their measurements and actively hunt for what they’re missing.

Most importantly, they’ll be organisations led by people who know themselves. Who understand their own biases, who can distinguish between reasoning and rationalising, who have the humility to admit uncertainty and the patience to sit with it. Because in the end, the quality of our decisions cannot exceed the quality of our self knowledge.

The famine won’t end by consuming more data. It will end when we learn to digest what we already have: slowly, carefully, wisely. When we stop mistaking the swamp for a lake, the noise for a signal, and the comfortable lie for the inconvenient truth.

The first step in that transformation is the hardest one of all: admitting that we don’t know nearly as much as we think we do. Not about our customers, not about our markets, and certainly not about ourselves.

The famine won’t end until we stop gorging and start digesting.