Disaster recovery is one of the most comforting practices in enterprise technology and one of the least honest. Organisations spend significant time and money designing DR strategies, running carefully choreographed exercises, producing polished post exercise reports, and reassuring themselves that they are prepared for major outages. The problem is not intent. The problem is that most DR exercises are optimised to demonstrate control and preparedness in artificial conditions, while real failures are chaotic, asymmetric and hostile to planning. When outages occur under real load, the assumptions underpinning these exercises fail almost immediately.

What most organisations call disaster recovery is closer to rehearsal than resilience. It tests whether people can follow a script, whether environments can be brought online when nothing else is going wrong, and whether senior stakeholders can be reassured. It does not test whether systems can survive reality.

1. DR Exercises Validate Planning Discipline, Not Failure Behaviour

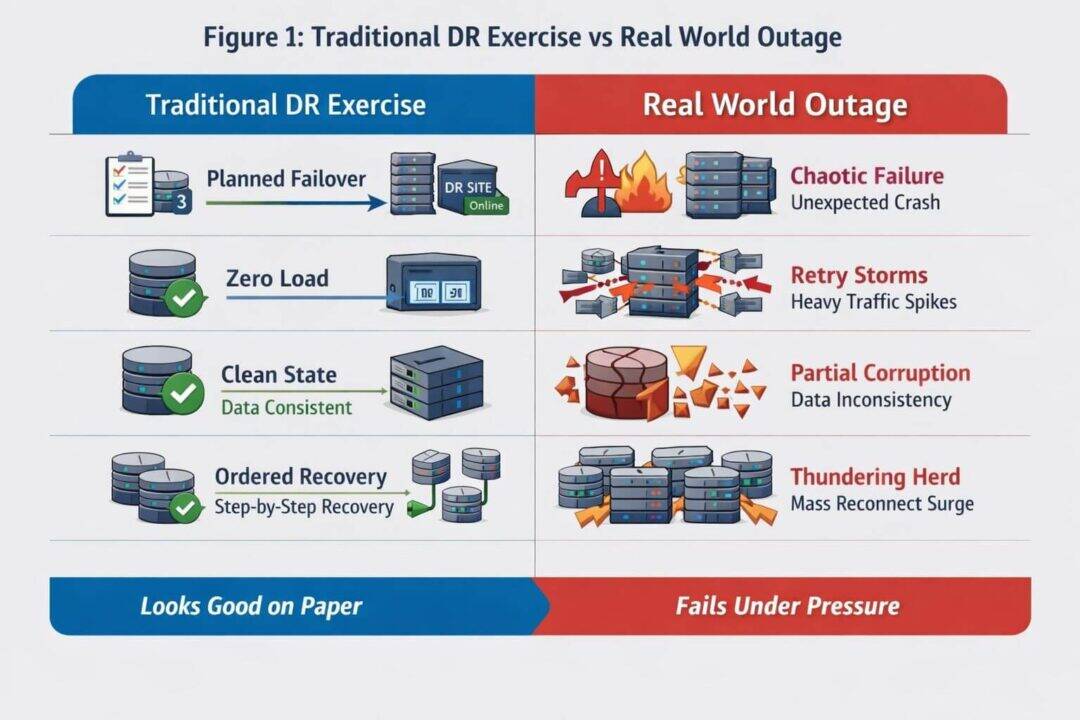

Traditional DR exercises are run like projects. They are planned well in advance, aligned to change freezes, coordinated across teams, and executed when everyone knows exactly what is supposed to happen. This alone invalidates most of the conclusions drawn from them. Real outages are not announced, they do not arrive at convenient times, and they rarely fail cleanly. They emerge as partial failures, ambiguous symptoms and cascading side effects. Alerts contradict each other, dashboards lag reality, and engineers are forced to reason under pressure with incomplete information.

A recovery strategy that depends on precise sequencing, complete information and the availability of specific individuals is fragile by definition. The more a DR exercise depends on human coordination to succeed, the less likely it is to work when humans are stressed, unavailable or wrong. Resilience is not something that can be planned into existence through documentation. It is an emergent property of systems that behave safely when things go wrong without requiring perfect execution.

2. Recovery Is Almost Always Tested in the Absence of Load

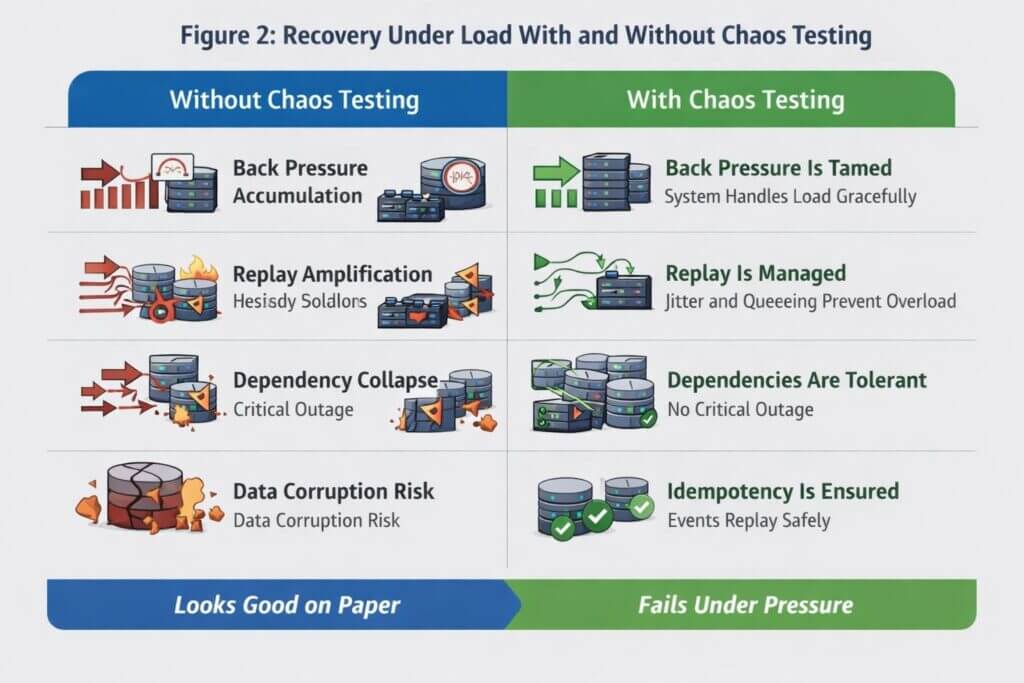

Figure 2: Recovery Under Load With and Without Chaos Testing

The single most damaging flaw in DR testing is that it is almost always performed when systems are idle. Queues are empty, clients are disconnected, traffic is suppressed, and downstream systems are healthy. This creates a deeply misleading picture of recoverability. In real outages, load does not disappear. It concentrates. Clients retry, SDKs back off and then retry again, load balancers redistribute traffic aggressively, queues accumulate messages faster than they can be drained, and databases slow down at precisely the moment demand spikes.

Back pressure and integration dependencies are the defining characteristic of real recovery scenarios, and it is almost entirely absent from DR exercises. A system that starts cleanly with no load and all its dependencies ready for traffic, may never become healthy when forced to recover while saturated and partially integrated. Recovery logic that looks correct in isolation frequently collapses when subjected to retry storms and backlog replays. Testing recovery without load is equivalent to testing a fire escape in an empty building and declaring it safe.

3. Recovery Commonly Triggers the Second Outage

DR plans tend to assume orderly reconnection. Services are expected to come back online, accept traffic gradually, and stabilise. Reality delivers the opposite. When systems reappear, clients reconnect simultaneously, message brokers attempt to drain entire backlogs at once, caches stampede databases, authentication systems spike, and internal rate limits are exceeded by internal callers rather than external users.

This thundering herd effect means that recovery itself often becomes the second outage, frequently worse than the first. Systems may technically be up while remaining unusable because they are overwhelmed the moment they re enter service. DR exercises rarely expose this behaviour because load is deliberately suppressed, leading organisations to confuse clean startup with safe recovery.

4. Why Real World DR Testing Is So Hard

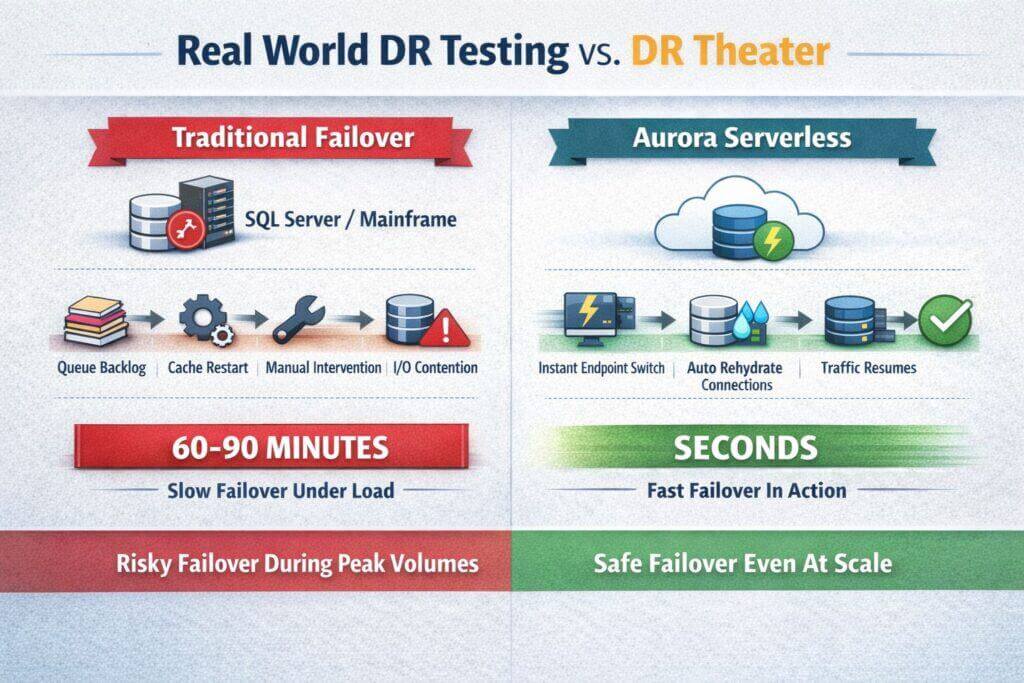

The uncomfortable truth is that most organizations avoid real world DR testing not because they are lazy or incompetent, but because the technology they run makes realistic testing commercially irrational.

In traditional enterprise estates a genuine failover is not a minor operational event. A large SQL Server estate or a mainframe environment routinely takes well over an hour to fail over cleanly, and that is assuming everything behaves exactly as designed. During that window queues back up, batch windows are missed, downstream systems time out, and customers feel the impact immediately. Pulling the pin on a system like this during peak volumes is not a test, it is a deliberate business outage. No executive will approve that, and nor should they.

This creates an inevitable compromise. DR tests are scheduled during low load periods, often weekends or nights, precisely when the system behaves best. The back pressure that exists during real trading hours is absent. Cache warm up effects are invisible. Connection storms never happen. Latent data consistency problems remain hidden. The test passes, confidence is reported upward, and nothing meaningful has actually been proven.

The core issue is not testing discipline, it is recovery time characteristics. If your recovery time objective is measured in hours, then every real test carries a material business risk. As a result, organizations rationally choose theater over truth.

Change the technology and the equation changes completely. Platforms like Aurora Serverless fundamentally alter the cost of failure. A failover becomes an operational blip measured in seconds rather than an existential event measured in hours. Endpoints are reattached, capacity is rehydrated automatically, and traffic resumes quickly enough that controlled testing becomes possible even with real workloads. Once confidence is built at lower volumes, the same mechanism can be exercised progressively closer to peak without taking the business hostage.

This is the key distinction most DR conversations miss. You cannot meaningfully test DR if the act of testing is itself catastrophic. Modern architectures that fail fast and recover fast are not just operationally elegant, they are the only ones that make honest DR validation feasible. Everything else optimizes for paperwork, not resilience.

5. Availability Is Tested While Correctness Is Ignored

Most DR exercises optimise for availability signals rather than correctness. They focus on whether systems start, endpoints respond and dashboards turn green, while ignoring whether the system is still “right”. Modern architectures are asynchronous, distributed and event driven. Outages cut through workflows mid execution. Transactions may be partially applied, events may be published but never consumed, compensating actions may not run, and side effects may occur without corresponding state changes.

DR testing almost never validates whether business invariants still hold after recovery. It rarely checks for duplicated actions, missing compensations or widened consistency windows. Availability without correctness is not resilience. It is simply data corruption delivered faster.

6. Idempotency Is Assumed Rather Than Proven

Many systems claim idempotency at an architectural level, but real implementations are usually only partially idempotent. Idempotency keys are often scoped incorrectly, deduplication windows expire too quickly, global uniqueness is not enforced, and side effects are not adequately guarded. External integrations frequently replay blindly, amplifying the problem.

Outages expose these weaknesses because retries occur across multiple layers simultaneously. Messages are delivered more than once, requests are replayed long after original context has been lost, and systems are forced to process duplicates at scale. DR exercises rarely test this behaviour under load. They validate that systems start, not that they behave safely when flooded with replays. Idempotency that only works in steady state is not idempotency. It is an assumption waiting to fail.

7. DNS and Replication Lag Are Treated as Minor Details

DNS based failover is a common component of DR strategies because it looks clean and simple on diagrams. In practice it is unreliable and unpredictable. TTLs are not respected uniformly, client side caches persist far longer than expected, mobile networks are extremely sticky, corporate resolvers behave inconsistently, and CDN propagation is neither instantaneous nor symmetrical.

During real incidents, traffic often arrives from both old and new locations for extended periods. Systems must tolerate split traffic and asymmetric routing rather than assuming clean cutover. DR exercises that expect DNS to behave deterministically are rehearsing a scenario that almost never occurs in production.

8. Hidden Coupling Between Domains Undermines Recovery

Most large scale recovery failures are not caused by the system being recovered, but by something it depends on. Shared authentication services, centralised configuration systems, common message brokers, logging pipelines and global rate limits quietly undermine isolation. During DR exercises these couplings remain invisible because everything is brought up together in a controlled order. In real outages, dependencies fail independently, partially and out of sequence.

True resilience requires domain isolation with explicitly bounded blast radius. If recovery of one system depends on the health of multiple others, none of which are isolated, then recovery is fragile regardless of how well rehearsed it is.

9. Human Factors Are Removed From the Equation

DR exercises assume ideal human conditions. The right people are available, everyone knows it is a test, stress levels are low, and communication is structured and calm. Real incidents are defined by the opposite conditions. People are tired, unavailable or already overloaded, context is missing, and decisions are made under extreme cognitive load.

Systems that require heroics to recover are not resilient. They are brittle. Good systems assume humans will be late, distracted and wrong, and still recover safely.

10. DR Is Designed for Audit Cycles, Not Continuous Failure

Most DR programs exist to satisfy auditors, regulators and risk committees rather than to survive reality. This leads to annual exercises, static runbooks, binary success metrics and a complete absence of continuous feedback. Meanwhile production systems change daily.

A DR plan that is not continuously exercised against live systems is obsolete by default. The confidence it provides is inversely proportional to its accuracy.

11. Chaos Testing Is the Only Honest Substitute

Real resilience is built by failing systems while they are doing real work. That means killing instances under load, partitioning networks unpredictably, breaking dependencies intentionally, injecting latency and observing the blast radius honestly. Chaos testing exposes retry amplification, back pressure collapse, hidden coupling and unsafe assumptions that scripted DR exercises systematically hide.

It is uncomfortable and politically difficult, but it is the only approach that resembles reality. Fortunately, some of the risk of chaos testing can be replicated in a UAT environment. But this requires investment and commitment from senior leaders that understand the value of these kinds of tests. Additionally, actual production outages can be reviewed forensically to essentially give you a “free lesson”, if you have invested in accurate monitoring and take the time to review all production failures.

12. What Systems Should Actually Be Proven To Do

A meaningful resilience strategy does not ask whether systems can be recovered quietly. It proves, continuously, that systems can recover under sustained load, tolerate duplication safely, remain isolated from unrelated domains, degrade gracefully, preserve business invariants and recover with minimal human coordination even when failure timing and scope are unpredictable.

Anything less is optimism masquerading as engineering.

13. The Symmetrical Failure

One of the most dangerous and least discussed failure modes in modern systems is what can be described as a symmetrical failure. It is dangerous precisely because it is fast, silent, and often irreversible by the time anyone realises what has happened.

Imagine a table being accidentally dropped from a production database. In an environment using synchronous replication, near synchronous replication, or block level storage replication, that change is propagated almost immediately to the disaster recovery environment. Within seconds, both production and DR contain the same fault. The table is gone everywhere. At that point DR is not degraded or partially useful. It is completely useless.

This is the defining characteristic of a symmetrical failure. The failure is faithfully replicated across every environment. Replication does not discriminate between correct state and incorrect state. It simply copies bytes. From the outside, everything still looks healthy. Replication is green. Storage is in sync. Latency is low. And yet the system has converged perfectly on a broken outcome.

This class of failure is not limited to dropped tables. Any form of logical corruption that is replicated at the physical or block layer will be propagated without validation. Index corruption, application bugs that write bad data, schema changes gone wrong, runaway batch jobs, or subtle data poisoning all behave the same way. Organisations relying heavily on block level replication often underestimate this risk because the tooling frames faster replication as increased safety. In reality, faster replication often increases the blast radius.

Some symmetrical failures can be rolled back quickly. A small table dropped and detected immediately might be recoverable from backups within an acceptable window. Others are far more intrusive. Large tables, high churn datasets, or corruption detected hours or days later can push recovery times far beyond any realistic business RTO. At that point the discussion is no longer about disaster recovery maturity, but about how long the business can survive without the system.

These failure events must be explicitly designed for, with a fixation on recovery time objectives rather than recovery point objectives alone. RPO answers how much data you might lose. RTO determines whether the business survives the incident. To achieve meaningful RTOs, organisations may need to impose constraints such as maximum database sizes, maximum table sizes, stricter data isolation, or delayed and logically validated replicas. In many cases, achieving the required RTO means changing the architecture rather than tuning the existing one.

If you want resilience, you have to accept that it will not emerge from faster replication or more frequent DR tests. It emerges from designing systems that can tolerate mistakes, corruption, and human error without collapsing instantly.

14. Conclusion

Most disaster recovery exercises do not fail because teams are incompetent. They fail because they test the wrong thing. They validate restart in calm conditions, without load, pressure or ambiguity. That proves very little about how systems and organisations behave when reality intervenes.

Traditional DR misses entire classes of failure including symmetrical failures, silent corruption, hidden coupling, governance paralysis and human breakdown under stress. A DR environment that faithfully mirrors production is only useful if production is still correct and if the organisation can act decisively when it is not.

The next question leaders inevitably ask is, “what is this going to cost?” The uncomfortable but honest answer is that if resilience is done properly, it is not a project or a line item. It is a lifestyle choice. It becomes embedded in how the organisation thinks about architecture, limits, failure and recovery. It shapes design decisions long before incidents occur.

In many cases, other than time and focus, there is little direct investment required. In fact, resilience work often reduces costs. That monolithic 100 terabyte database that runs your entire organisation and requires specialised hardware, specialised skills and multi hour recovery windows is usually a design failure, not a necessity. When it goes on a diet, recovery times collapse. Hardware requirements shrink. Operational complexity drops.

More importantly, resilient designs often introduce stand in capabilities. Caches, queues, read only replicas and degraded modes allow the business to continue processing transactions while recovery is underway. The organisation does not stop simply because the primary system is being repaired. Recovery becomes a background activity rather than a full stop event.

True resilience is not achieved through bigger DR budgets or more elaborate exercises. It is achieved by changing how systems are designed, how limits are enforced and how failure is expected and absorbed. If your recovery strategy only works when everything goes to plan, it is not resilience. It is optimism masquerading as engineering.