1. Introduction

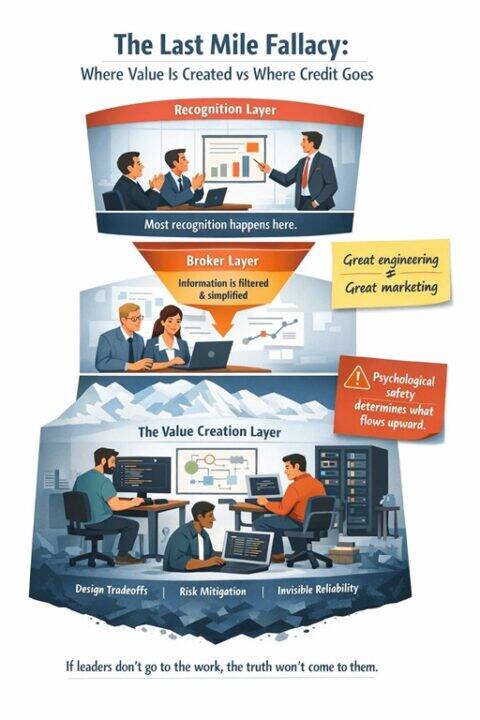

Organisations like to believe they reward outcomes. In reality, they reward visibility. This is the essence of the Last Mile Fallacy: the mistaken belief that the final visible step in a chain of work is where most of the value was created. We tip the waiter rather than the chef, praise the presenter rather than the people who built the system, and congratulate the messenger rather than the makers. The last mile feels real because it has a face, a voice, and a narrative that fits neatly into a meeting. The earlier miles are quieter, messier, and far harder to explain, so they are systematically undervalued.

2. Why the Last Mile Feels Like the Work

In a restaurant, tipping the waiter makes emotional sense. The waiter is the person we interact with, the person who absorbs our frustration and responds to our gratitude. But this social convention quietly becomes a value model inside organisations. The kitchen created the asset through skill, preparation, and repeated invisible decisions, yet the reward follows the interaction rather than the creation. Over time, companies internalise this logic and begin to believe that delivery, reporting, and presence are the work, rather than the final expression of it.

3. How This Manifests in Technology Organisations

In technology teams, the “waiter” is often the person reporting progress. They attend the meetings, translate uncertainty into status updates, and turn complex engineering realities into something consumable. When detailed questions arise, the response is often that they are not close to the detail and will check with the team, yet the recognition and perceived ownership remain firmly with them. This is rarely malicious. It is structural. The system rewards those who can package work, not those who quietly do it.

4. Where Engineering Value Is Actually Created

Most engineering value is created long before anything becomes visible. It appears in design tradeoffs that avoid future failure, in performance headroom that only matters on the worst day, and in risks retired early enough that no one ever knows they existed. Great engineering is often deliberately invisible. When systems work, there is nothing to point at. This creates a fundamental mismatch: great engineering does not naturally market itself, and engineers are rarely motivated to try.

5. Great Engineering Is Not Great Marketing

Engineers are intrinsically poor at being seen and heard, not because they lack confidence or capability, but because their incentives are different. Precision matters more than persuasion. Acknowledging uncertainty is a strength, not a weakness. Over claiming feels dishonest, and time spent talking is time not spent fixing the problem. What looks like poor communication from the outside is often professional integrity on the inside. Expecting engineers to compensate for this by becoming self marketers misunderstands both the role and the culture.

6. Psychological Safety and the Broker Layer

Because it is often unsafe to speak openly, information rarely flows directly from engineers to senior leadership. Saying that a deadline is fictional, that a design is fragile, or that a system is one person away from failure carries real career risk. As a result, organisations evolve a broker layer that filters, softens, and sanitises reality before it travels upward. Leadership frequently mistakes this calm, polished narrative for control, when in fact it is distance. The truth still exists, but it has been made comfortable.

7. A Legitimate Counter Argument: When Work Really Is a Commodity

There are domains where the Last Mile Fallacy is less of a fallacy and more of an economic reality. Construction is a useful example. Laying bricks is physically demanding, highly skilled work, yet bricklayers are often interchangeable. The intellectual property of the building exists before the first brick is laid. The architect, engineer, and planner have already made the critical decisions. The bricklayer is executing a predefined plan, acting on instructions rather than solving open ended problems. In this context, replacing the individual doing the work does not meaningfully alter the outcome, because the value was created upstream and encoded into the design.

8. Why Software Engineering Is Fundamentally Different

Software engineering does not work this way. The value does not sit fully formed before execution begins. Engineers are not simply following instructions; they are continuously solving problems, making trade offs, and adapting to constraints in real time. You are not paying for keystrokes or lines of code. You are paying for judgment, efficiency, and the ability to reach a desired outcome under uncertainty. Two engineers given the same requirements will produce radically different systems in terms of performance, resilience, cost, and long term maintainability. The intellectual property is created during the work, not before it.

9. Presence Without Proximity

This distinction makes the organisational behaviour even more ironic. Many organisations demand a return to the office in the name of proximity, collaboration, and culture, yet senior leaders rarely leave their own rooms, floors, or meeting cycles to engage directly with the teams doing this problem solving work. Call centres remain unvisited, engineering floors remain symbolic, and frontline reality is discussed rather than observed. The distance remains intact, even as the optics change.

10. Key Man Risk Is Consistently Misplaced

Ask where key man risk sits and many organisations will point to programme leads or senior managers. In reality, the risk sits with the engineer who understands the legacy edge case, the operator who knows which alert lies, or the developer who fixed the outage at two in the morning. These people are not interchangeable because the intellectual property lives in their decisions and experience. When they leave, knowledge evaporates. When brokers leave, slides are rewritten.

11. Leadership’s Actual Responsibility

In an engineering led organisation, leadership is not there to extract updates or admire dashboards. Leadership exists to go to the work, to create enough psychological safety that people can speak honestly, and to translate engineering reality into organisational decisions. Engineers should not be forced to become marketers in order to be heard. Leaders must do the harder work of listening, observing, and engaging deeply enough that truth can surface without fear.

12. Escaping the Last Mile Fallacy (Practical Ways Out)

Escaping the Last Mile Fallacy is not about better reporting, slicker decks, or more polished narratives. It is about deliberately collapsing the distance between those who create value and those who make decisions. That distance is organisational, cultural, and often emotional. Closing it requires intent, tolerance, and leadership courage.

12.1 Let the Makers Give the Demos

Wherever possible, the people who wrote the software should give the demos, even when the audience is Exco or the board. This will feel uncomfortable at first. Engineers may give answers that are technically honest but politically naive. That is not a failure; it is a signal that reality is finally present in the room.

If leadership cannot tolerate imperfect phrasing in exchange for truth, the organisation will always optimise for storytelling over substance. Supporting these presenters publicly is critical. The moment someone is punished or undermined for honest technical communication, the organisation snaps back into theatre mode.

12.2 Reward Truth Early, Not Just Delivery at the End

Organisations say they want transparency, but often only reward success narratives. Escaping the fallacy requires explicitly rewarding early truth, especially when that truth is inconvenient.

When engineers raise concerns about scope, complexity, architectural debt, or timelines early, that should increase trust, not decrease it. Leaders must model this by responding with curiosity rather than defensiveness. If bad news is only safe once it is irreversible, the last mile will always lie.

12.3 Train Leadership to Appreciate How Hard Value Is to Deliver

Many leadership decisions are made without any lived appreciation of how difficult modern software delivery actually is. This is not a moral failing, but it is a structural one.

Leadership development should include exposure to real delivery work: shadowing teams, walking through systems, understanding tradeoffs, and seeing the invisible labour involved in keeping systems stable while they evolve. Without this context, expectations will always skew optimistic and attribution will always drift upward.

12.4 Institutionalise Skip Level Engagement

Skip level engagement should not be treated as an exceptional event or a crisis intervention. It should be normalised as a healthy organisational reflex.

Leaders should regularly reach into the organisation and speak directly with staff at all levels, with layers of management present but not filtering the interaction. The goal is not to bypass managers, but to remove information distortion. Real understanding does not survive too many translations.

12.5 Give Exco Direct Access to Engineers and Their Work

Executive teams should have access to sessions where they can talk directly to engineers, see what they are working on, and ask questions without intermediaries. These are not status updates. They are learning sessions.

When leaders take a genuine interest in the work, engineers feel seen, complexity becomes visible, and decisions improve. When leaders rely exclusively on summaries, the last mile becomes the only voice that matters.

12.6 Treat Asking Dumb Questions as a Leadership Responsibility

If you are privileged to be a leader, you must make your peace with asking questions that feel dumb. The alternative is pretending to understand while making decisions in the dark.

Asking naive questions is not a weakness. It is how leaders escape the prison of curated narratives. It signals humility, invites clarity, and creates space for real dialogue. Leaders who only ask impressive questions are usually optimising for image, not understanding.

12.7 Create Senior Technical Career Paths That Do Not Force Management

One of the most subtle drivers of the Last Mile Fallacy is the way organisations structure career progression. In many companies, engineers eventually hit a ceiling in individual contributor roles and are forced to convert into managers to progress, gain status, or earn more. This is a mistake.

Senior designations such as Staff Engineer, Principal Engineer, and Distinguished Engineer create a parallel path that allows exceptional contributors to remain close to the work. These roles recognise impact through technical leadership, system stewardship, mentoring, and architectural judgement rather than headcount ownership.

Crucially, these roles must be financially and socially equivalent to management tracks. If technical leadership is treated as a consolation prize, the organisation will still drain its best engineers away from real work and into coordination roles they may not want or be good at.

Clear contributor career paths reduce the pressure to perform value through visibility. They keep expertise where it matters most and ensure that the people shaping the systems are the people who deeply understand them.

12.8 Shift Recognition from Visibility to Impact

Finally, organisations must consciously shift what they recognise and reward. Airtime, presentation polish, and narrative control are poor proxies for value creation.

Recognition systems should elevate impact, craft, resilience, and problem solving, even when that work is invisible or unglamorous. Until incentives change, behaviour will not. The last mile will always attract disproportionate credit because the system is designed that way.

Organisations that escape the Last Mile Fallacy do not do so accidentally. They redesign how leadership engages with work, how truth flows, and how value is recognised. Leaders go to the work, rather than waiting for the work to come to them.

13. Conclusion

Software engineering is not bricklaying. It is creative, judgement heavy problem solving carried out under uncertainty, over time, and across layers of invisible complexity. When organisations treat it as a commodity that can be fully represented through slides and summaries, they fundamentally misunderstand where value is created and where risk accumulates.

The Last Mile Fallacy persists not because leaders are malicious, but because distance is convenient. It is easier to consume narratives than to engage with reality. It is easier to reward visibility than to understand contribution. But that convenience comes at a cost: poor decisions, frustrated teams, and organisations that slowly lose their ability to execute.

Escaping the fallacy is therefore not an intellectual exercise. It is a leadership practice. It requires humility, presence, and a willingness to sit with discomfort. It requires leaders to ask questions that expose what they do not know, to listen to people who are not polished communicators, and to value truth over theatre.

If you are privileged to lead, your job is not to be protected from complexity. Your job is to engage with it. Go to the demos. Sit with the engineers. Ask the dumb questions. Collapse the distance.

Because the closer leadership is to real work, the harder it becomes to confuse motion with progress, and the easier it becomes to recognise where value is actually created.

Andrew Baker, this truly resonates with me. You’ve hit the nail on the head. Reading these words from a leader hits differently and I’m sure your teams are lucky to be led by someone who understands this and is able to link it to recognition and reward; the structural designs of organizations and teams; and the culture and leadership developments within organizations.

You’ve articulated it from the Engineering perspective however this applies to many roles. In my experience, I see it in my Legal Practice, I see it in my Data Governance function and especially in my Governance, Risk Management & Compliance (GRC) work with the engineering and tech teams.

There is little appreciation of where impact truly gets created and we encourage team work, collaboration and co creation, yet we mainly recognize and hear the last mile delivery. The fruits of the labour do not return downstream. I agree with you that its structural, organisational and cultural mostly, and not because of malice. We need to work on this. You’ve helped start by identifying the last mile fallacy, now its up to each of us to do something about it.

Thank you.