Darwinian Architecture Philosophy

How Domain Isolation Creates Evolutionary Pressure for Better Software

After two decades building trading platforms and banking systems, I’ve watched the same pattern repeat itself countless times. A production incident occurs. The war room fills. And then the finger pointing begins.

“It’s the database team’s problem.” “No, it’s that batch job from payments.” “Actually, I think it’s the new release from the cards team.” Three weeks later, you might have an answer. Or you might just have a temporary workaround and a room full of people who’ve learned to blame each other more effectively.

This is the tragedy of the commons playing out in enterprise technology, and it’s killing your ability to evolve.

1. The Shared Infrastructure Trap

Traditional enterprise architecture loves shared infrastructure. It makes intuitive sense: why would you run fifteen database clusters when one big one will do? Why have each team manage their own message broker when a central platform team can run one for everybody? Economies of scale. Centralised expertise. Lower costs.

Except that’s not what actually happens.

What happens is that your shared Oracle RAC cluster becomes a battleground. The trading desk needs low latency queries. The batch processing team needs to run massive overnight jobs. The reporting team needs to scan entire tables. Everyone has legitimate needs, and everyone’s needs conflict with everyone else’s. The DBA team becomes a bottleneck, fielding requests from twelve different product owners, all of whom believe their work is the priority.

When the CPU spikes to 100% at 2pm on a Tuesday, the incident call has fifteen people on it, and nobody knows whose query caused it. The monitoring shows increased load, but the load comes from everywhere. Everyone claims their release was tested. Everyone points at someone else.

This isn’t a technical problem. It’s an accountability problem. And you cannot solve accountability problems with better monitoring dashboards.

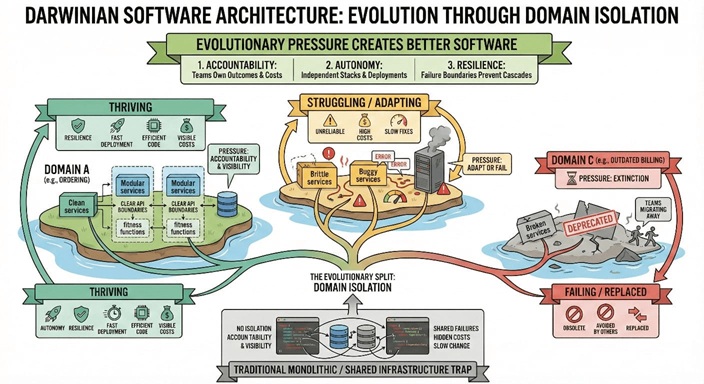

2. Darwinian Pressure in Software Systems

Nature solved this problem billions of years ago. Organisms that make poor decisions suffer the consequences directly. There’s no committee meeting to discuss why the antelope got eaten. The feedback loop is immediate and unambiguous. Whilst nobody wants to watch it, teams secretly take comfort in not being the limping buffalo at the back of the herd. Teams get fit, they resist decisions that will put them in an unsafe place as they know they will receive an uncomfortable amount of focus from senior management.

Modern software architecture can learn from this. When you isolate domains, truly isolate them, with their own data stores, their own compute, their own failure boundaries, you create Darwinian pressure. Teams that write inefficient code see their own costs rise. Teams that deploy buggy releases see their own services degrade. Teams that don’t invest in resilience suffer their own outages.

There’s no hiding. There’s no ambiguity. There’s no three week investigation to determine fault. There is no watered down document that hints at the issue, but doesn’t really call it out, as all the teams couldn’t agree on something more pointed. The feedback loop tightens from weeks to hours, sometimes minutes.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about learning. When the consequences of your decisions land squarely on your own service, you learn faster. You care more. You invest in the right things because you directly experience the cost of not investing.

3. The Architecture of Isolation

Achieving genuine domain isolation requires more than just drawing boxes on a whiteboard and calling them “microservices.” It requires rethinking how domains interact with each other and with their data.

Data Localisation Through Replication

The hardest shift for most organisations is accepting that data duplication isn’t a sin. In a shared database world, we’re taught that the single source of truth is sacred. Duplicate data creates consistency problems. Normalisation is good.

But in a distributed world, the shared database is the coupling that prevents isolation. If three domains query the same customer table, they’re coupled. An index change that helps one domain might destroy another’s performance. A schema migration requires coordinating across teams. The tragedy of the commons returns.

Instead, each domain should own its data. If another domain needs that data, replicate it. Event driven patterns work well here: when a customer’s address changes, publish an event. Subscribing domains update their local copies. Yes, there’s eventual consistency. Yes, the data might be milliseconds or seconds stale. But in exchange, each domain can optimise its own data structures for its own access patterns, make schema changes without coordinating with half the organisation, and scale its data tier independently.

Queues as Circuit Breakers

Synchronous service to service calls are the other hidden coupling that defeats isolation. When the channel service calls the fraud service, and the fraud service calls the customer service, you’ve created a distributed monolith. A failure anywhere propagates everywhere. An outage in customer data brings down payments.

Asynchronous messaging changes this dynamic entirely. When a payment needs fraud checking, it drops a message on a queue. If the fraud service is slow or down, the queue absorbs the backlog. The payment service doesn’t fail, it just sees increased latency on fraud decisions. Customers might wait a few extra seconds for approval rather than seeing an error page.

This doesn’t make the fraud service’s problems disappear. The fraud team still needs to fix their outage, but you can make business choices about how to deal with the outage. For example, you can choose to bypass the checks for payments to “known” beneficiaries or below certain threshold values, so the blast radius is contained and can be managed. The payments team’s SLAs aren’t destroyed by someone else’s incident. The Darwinian pressure lands where it belongs: on the team whose service is struggling.

Proxy Layers for Graceful Degradation

Not everything can be asynchronous. Sometimes you need a real time answer. But even synchronous dependencies can be isolated through intelligent proxy layers.

A well designed proxy can cache responses, serve stale data during outages, fall back to default behaviours, and implement circuit breakers that fail fast rather than hanging. When the downstream service returns, the proxy heals automatically.

The key insight is that the proxy belongs to the calling domain, not the called domain. The payments team decides how to handle fraud service failures. Maybe they approve transactions under a certain threshold automatically. Maybe they queue high value transactions for manual review. The fraud team doesn’t need to know or care, they just need to get their service healthy again.

4. Escaping the Monolith: Strategies for Service Eviction

Understanding the destination is one thing. Knowing how to get there from where you are is another entirely. Most enterprises aren’t starting with a blank slate. They’re staring at a decade old shared Oracle database with three hundred stored procedures, an enterprise service bus that routes traffic for forty applications, and a monolithic core banking system that everyone is terrified to touch.

The good news is that you don’t need to rebuild everything from scratch. The better news is that you can create structural incentives that make migration inevitable rather than optional.

Service Eviction: Making the Old World Uncomfortable

Service eviction is the deliberate practice of making shared infrastructure progressively less attractive to use while making domain-isolated alternatives progressively more attractive. This isn’t about being obstructive. It’s about aligning incentives with architecture.

Start with change management. On shared infrastructure, every change requires coordination. You need a CAB ticket. You need sign-off from every consuming team. You need a four week lead time and a rollback plan approved by someone three levels up. The change window is 2am Sunday, and if anything goes wrong, you’re in a war room with fifteen other teams.

On domain isolated services, changes are the team’s own business. They deploy when they’re ready. They roll back if they need to. Nobody else is affected because nobody else shares their infrastructure. The contrast becomes visceral: painful, bureaucratic change processes on shared services versus autonomous, rapid iteration on isolated ones.

This isn’t artificial friction. It’s honest friction. Shared infrastructure genuinely does require more coordination because changes genuinely do affect more people. You’re just making the hidden costs visible and letting teams experience them directly.

Data Localisation Through Kafka: Breaking the Database Coupling

The shared database is usually the hardest dependency to break. Everyone queries it. Everyone depends on its schema. Moving data feels impossibly risky.

Kafka changes the game by enabling data localisation without requiring big bang migrations. The pattern works like this: identify a domain that wants autonomy. Have the source system publish events to Kafka whenever relevant data changes. Have the target domain consume those events and maintain its own local copy of the data it needs.

Initially, this looks like unnecessary duplication. The data exists in Oracle and in the domain’s local store. But that duplication is exactly what enables isolation. The domain can now evolve its schema independently. It can optimise its indexes for its access patterns. It can scale its data tier without affecting anyone else. And critically, it can be tested and deployed without coordinating database changes with twelve other teams.

Kafka’s log based architecture makes this particularly powerful. New consumers can replay history to bootstrap their local state. The event stream becomes the source of truth for what changed and when. Individual domains derive their local views from that stream, each optimised for their specific needs.

The key insight is that you’re not migrating data. You’re replicating it through events until the domain no longer needs to query the shared database directly. Once every query can be served from local data, the coupling is broken. The shared database becomes a publisher of events rather than a shared resource everyone depends on.

The Strangler Fig: Gradual Replacement Without Risk

The strangler fig pattern, named after the tropical tree that gradually envelops and replaces its host, is the safest approach to extracting functionality from monoliths. Rather than replacing large systems wholesale, you intercept specific functions at the boundary and gradually route traffic to new implementations.

Put a proxy in front of the monolith. Initially, it routes everything through unchanged. Then, one function at a time, build the replacement in the target domain. Route traffic for that function to the new service while everything else continues to hit the monolith. When the new service is proven, remove the old code from the monolith.

The beauty of this approach is that failure is localised and reversible. If the new service has issues, flip the routing back. The monolith is still there, still working. You haven’t burned any bridges. You can take the time to get it right because you’re not under pressure from a hard cutover deadline.

Combined with Kafka-based data localisation, the strangler pattern becomes even more powerful. The new domain service consumes events to build its local state, the proxy routes relevant traffic to it, and the old monolith gradually loses responsibilities until what remains is small enough to either rewrite completely or simply turn off.

Asymmetric Change Management: The Hidden Accelerator

This is the strategy that sounds controversial but works remarkably well: make change management deliberately asymmetric between shared services and domain isolated services.

On the shared database or monolith, changes require extensive governance. Four week CAB cycles. Impact assessments signed off by every consuming team. Mandatory production support during changes. Post-implementation reviews. Change freezes around month-end, quarter-end, and peak trading periods.

On domain-isolated services, teams own their deployment pipeline end to end. They can deploy multiple times per day if their automation supports it. No CAB tickets. No external sign offs. If they break their own service, they fix their own service.

This asymmetry isn’t punitive. It reflects genuine risk. Changes to shared infrastructure genuinely do have broader blast radius. They genuinely do require more coordination. You’re simply making the cost of that coordination visible rather than hiding it in endless meetings and implicit dependencies.

The effect is predictable. Teams that want to move fast migrate to domain isolation. Teams that are comfortable with quarterly releases can stay on shared infrastructure. Over time, the ambitious teams have extracted their most critical functionality into isolated domains. What remains on shared infrastructure is genuinely stable, rarely changing functionality that doesn’t need rapid iteration.

The natural equilibrium is that shared infrastructure becomes genuinely shared: common utilities, reference data, things that change slowly and benefit from centralisation. Everything else migrates to where it can evolve independently.

The Migration Playbook

Put it together and the playbook looks like this:

First, establish Kafka as your enterprise event backbone. Every system of record publishes events when data changes. This is table stakes for everything else.

Second, identify a domain with high change velocity that’s suffering under shared infrastructure governance. They’re your early adopter. Help them establish their own data store, consuming events from Kafka to maintain local state.

Third, put a strangler proxy in front of relevant monolith functions. Route traffic to the new domain service. Prove it works. Remove the old implementation.

Fourth, give the domain team autonomous deployment capability. Let them experience the difference between deploying through a four-week CAB cycle versus deploying whenever they’re ready.

Fifth, publicise the success. Other teams will notice. They’ll start asking for the same thing. Now you have demand driven migration rather than architecture-mandated migration.

The key is that you’re not forcing anyone to migrate. You’re creating conditions where migration is obviously attractive. The teams that care about velocity self select. The shared infrastructure naturally shrinks to genuinely shared concerns.

5. The Cultural Shift

Architecture is easy compared to culture. You can draw domain boundaries in a week. Convincing people to live within them takes years.

The shared infrastructure model creates a particular kind of learned helplessness. When everything is everyone’s problem, nothing is anyone’s problem. Teams optimise for deflecting blame rather than improving reliability. Political skills matter more than engineering skills. The best career move is often to avoid owning anything that might fail.

Domain isolation flips this dynamic. Teams own their outcomes completely. There’s nowhere to hide, but there’s also genuine autonomy. You can choose your own technology stack. You can release when you’re ready without coordinating with twelve other teams. You can invest in reliability knowing that you’ll reap the benefits directly.

This autonomy attracts a different kind of engineer. People who want to own things. People who take pride in uptime and performance. People who’d rather fix problems than explain why problems aren’t their fault.

The teams that thrive under this model are the ones that learn fastest. They build observability into everything because they need to understand their own systems. They invest in automated testing because they can’t blame someone else when their deploys go wrong. They design for failure because they know they’ll be the ones getting paged.

The teams that don’t adapt… well, that’s the Darwinian part. Their services become known as unreliable. Other teams design around them. Eventually, the organisation notices that some teams consistently deliver and others consistently struggle. The feedback becomes impossible to ignore.

6. Conway’s Law: Accepting the Inevitable, Rejecting the Unnecessary

Melvin Conway observed in 1967 that organisations design systems that mirror their communication structures. Fifty years of software engineering has done nothing to disprove him. Your architecture will reflect your org chart whether you plan for it or not.

This isn’t a problem to be solved. It’s a reality to be acknowledged. Your domain boundaries will follow team boundaries. Your service interfaces will reflect the negotiations between teams. The political realities of your organisation will manifest in your technical architecture. Fighting this is futile.

But here’s what Conway’s Law doesn’t require: shared suffering.

Traditional enterprise architecture interprets Conway’s Law as an argument for centralisation. If teams need to communicate, give them shared infrastructure to communicate through. If domains overlap, put the overlapping data in a shared database. The result is that Conway’s Law manifests not just in system boundaries but in shared pain. When one team struggles, everyone struggles. When one domain has an incident, twelve teams join the war room.

Domain isolation accepts Conway’s Law while rejecting this unnecessary coupling. Yes, your domains will align with your teams. Yes, your service boundaries will reflect organisational reality. But each team’s infrastructure can be genuinely isolated. Public cloud makes this trivially achievable through account-level separation.

Give each domain its own AWS account or Azure subscription. Their blast radius is contained by cloud provider boundaries, not just by architectural diagrams. Their cost allocation is automatic. Their security boundaries are enforced by IAM, not by policy documents. Their quotas and limits are independent. When the fraud team accidentally spins up a thousand Lambda functions, the payments team doesn’t notice because they’re in a completely separate account with separate limits.

Conway’s Law still shapes your domain design. The payments team builds payment services. The fraud team builds fraud services. The boundaries reflect the org chart. But the implementation of those boundaries can be absolute rather than aspirational. Account level isolation means that even if your domain design isn’t perfect, the consequences of imperfection are contained.

This is the insight that transforms Conway’s Law from a constraint into an enabler. You’re not fighting organisational reality. You’re aligning infrastructure isolation with organisational boundaries so that each team genuinely owns their outcomes. The communication overhead that Conway identified still exists, but it happens through well-defined APIs and event contracts rather than through shared database contention and incident calls.

7. The Transition Path

You can’t flip a switch and move from shared infrastructure to domain isolation overnight. The dependencies are too deep. The skills don’t exist. The organisational structures don’t support it.

But you can start. Pick a domain that’s struggling with the current model, probably one that’s constantly blamed for incidents they didn’t cause. Give them their own database, their own compute, their own deployment pipeline. Build the event publishing infrastructure so they can share data with other domains through replication rather than direct queries.

Watch what happens. The team will stumble initially. They’ve never had to think about database sizing or query optimisation because that was always someone else’s job. But within a few months, they’ll own it. They’ll understand their system in a way they never did before. Their incident response will get faster because there’s no ambiguity about whose system is broken.

More importantly, other teams will notice. They’ll see a team that deploys whenever they want, that doesn’t get dragged into incident calls for problems they didn’t cause, that actually controls their own destiny. They’ll start asking for the same thing.

This is how architectural change actually happens, not through mandates from enterprise architecture, but through demonstrated success that creates demand.

8. The Economics Question

I can already hear the objections. “This is more expensive. We’ll have fifteen databases instead of one. Fifteen engineering teams managing infrastructure instead of one platform team.”

To which I’d say: you’re already paying these costs, you’re just hiding them.

Every hour spent in an incident call where twelve teams try to figure out whose code caused the database to spike is a cost. Every delayed release because you’re waiting for a shared schema migration is a cost. Every workaround another team implements because your shared service doesn’t quite meet their needs is a cost. Every engineer who leaves because they’re tired of fighting political battles instead of building software is a cost.

Domain isolation makes these costs visible and allocates them to the teams that incur them. That visibility is uncomfortable, but it’s also the prerequisite for improvement.

And yes, you’ll run more database clusters. But they’ll be right sized for their workloads. You won’t be paying for headroom that exists only because you can’t predict which team will spike load next. You won’t be over provisioning because the shared platform has to handle everyone’s worst case simultaneously.

9. But surely AWS is shared infrastructure?

A common pushback when discussing domain isolation and ownership is: “But surely AWS is shared infrastructure?”

The answer is yes , but that observation misses the point of what ownership actually means in a Darwinian architectural model.

Ownership here is not about blame or liability when something goes wrong. It is about control and autonomy. The critical question is not who gets blamed, but who has the ability to act, change, and learn.

AWS operates under a clearly defined Shared Responsibility Model. AWS is responsible for the security of the cloud, the physical data centres, hardware, networking, and the underlying virtualization layers. Customers are responsible for security in the cloud, everything they configure, deploy, and operate on top of that platform.

Crucially, AWS gives you complete control over the things you are responsible for. You are not handed vague obligations without tools. You are given APIs, policy engines, telemetry, and automation primitives to fully own your outcomes. Identity and access management, network boundaries, encryption, scaling policies, deployment strategies, data durability, and recovery are all explicitly within your control.

This is why AWS being “shared infrastructure” does not undermine architectural ownership. Ownership is not defined by exclusive physical hardware; it is defined by decision-making authority and freedom to evolve. A team that owns its AWS account, VPC, services, and data can change direction without negotiating with a central platform team, can experiment safely within its own blast radius, and can immediately feel the consequences of poor design decisions.

That feedback loop is the point.

From a Darwinian perspective, AWS actually amplifies evolutionary pressure. Teams that design resilient, observable, well isolated systems thrive. Teams that cut corners experience outages, cost overruns, and operational pain, quickly and unambiguously. There is no shared infrastructure committee to absorb the consequences or hide failure behind abstraction layers.

So yes, AWS is shared infrastructure — but it is shared in a way that preserves local control, clear responsibility boundaries, and fast feedback. And those are the exact conditions required for domain isolation to work, and for better software to evolve over time.

10. Evolution, Not Design

The deepest insight from evolutionary biology is that complex, well adapted systems don’t emerge from top down design. They emerge from the accumulation of countless small improvements, each one tested against reality, with failures eliminated and successes preserved.

Enterprise architecture traditionally works the opposite way. Architects design systems from above. Teams implement those designs. Feedback loops are slow and filtered through layers of abstraction. By the time the architecture proves unsuitable, it’s too deeply embedded to change.

Domain isolation enables architectural evolution. Each team can experiment within their boundary. Good patterns spread as other teams observe and adopt them. Bad patterns get contained and eventually eliminated. The overall system improves through distributed learning rather than centralised planning.

This doesn’t mean architects become irrelevant. Someone needs to define the contracts between domains, design the event schemas, establish the standards for how services discover and communicate with each other. But the architect’s role shifts from designing systems to designing the conditions under which good systems can emerge.

10. The End State

I’ve seen organisations make this transition. It takes years, not months. It requires sustained leadership commitment. It forces difficult conversations about team structure and accountability.

But the end state is remarkable. Incident calls have three people on them instead of thirty. Root cause is established in minutes instead of weeks. Teams ship daily instead of quarterly. Engineers actually enjoy their work because they’re building things instead of attending meetings about who broke what.

Pain at the Source

The core idea is deceptively simple: put the pain of an issue right next to its source. When your database is slow, you feel it. When your deployment breaks, you fix it. The feedback loop is immediate and unambiguous.

But here’s what surprises people: this doesn’t make teams selfish. Far from it.

In the shared infrastructure world, teams spend enormous energy on defence. Every incident requires proving innocence. Every performance problem demands demonstrating that your code isn’t the cause. Every outage triggers a political battle over whose budget absorbs the remediation. Teams are exhausted not from building software but from fighting for survival in an environment of ambiguous, omnipresent enterprise guilt.

Domain isolation eliminates this overhead entirely. When your service has a problem, it’s your problem. There’s no ambiguity. There’s no blame game. There’s no three week investigation. You fix it and move on.

Cooperation, Not Competition

And suddenly, teams have energy to spare.

When the fraud team struggles with a complex caching problem, the payments team can offer to help. Not because they’re implicated, not because they’re defending themselves, but because they have genuine expertise and genuine capacity. They arrive as subject matter experts, and the fraud team receives them gratefully as such. There’s no suspicion that help comes with strings attached or that collaboration is really just blame shifting in disguise.

Teams become more cooperative in this world, not less. They show off where they’ve been successful. They write internal blog posts about their observability stack. They present at tech talks about how they achieved sub second deployments. Other teams gladly copy them because there’s no competitive zero sum dynamic. Your success doesn’t threaten my budget. Your innovation doesn’t make my team look bad. We’re all trying to build great software, and we can finally focus on that instead of on survival.

Breaking Hostage Dynamics

And you’re no longer hostage to hostage hiring.

In the shared infrastructure world, a single team can hold the entire organisation ransom. They build a group wide service. It becomes critical. It becomes a disaster. Suddenly they need twenty emergency engineers or the company is at risk. The service shouldn’t exist in the first place, but now it’s too important to fail and too broken to survive without massive investment. The team that created the problem gets rewarded with headcount. The teams that built sustainable, well-designed services get nothing because they’re not on fire.

Domain isolation breaks this perverse incentive. If a team builds a disaster, it’s their disaster. They can’t hold the organisation hostage because their blast radius is contained. Other domains have already designed around them with circuit breakers and fallbacks. The failing service can be deprecated, strangled out, or left to die without taking the company with it. Emergency hiring goes to teams that are succeeding and need to scale, not to teams that are failing and need to be rescued.

The Over Partitioning Trap

I should add a warning: I’ve also seen teams inflict shared pain on themselves, even without shared infrastructure.

They do this by hiring swathes of middle managers and over partitioning into tiny subdomains. Each team becomes responsible for a minuscule pool of resources. Nobody owns anything meaningful. To compensate, they hire armies of planners to try and align these micro teams. The teams fire emails and Jira tickets at each other to inch their ten year roadmap forward. Meetings multiply. Coordination overhead explodes. The organisation has recreated shared infrastructure pain through organisational structure rather than technology.

When something fails in this model, it quickly becomes clear that only a very few people actually understand anything. These elite few become the shared gatekeepers. Without them, no team can do anything. They’re the only ones who know how the pieces fit together, the only ones who can debug cross team issues, the only ones who can approve changes that touch multiple micro domains. You’ve replaced shared database contention with shared human contention. The bottleneck has moved from Oracle to a handful of exhausted architects.

It’s critical not to over partition into tiny subdomains. A domain should be large enough that a team can own something meaningful end to end. They should be able to deliver customer value without coordinating with five other teams. They should understand their entire service, not just their fragment of a service.

These nonsensical subdomains generally only occur when non technical staff have a disproportionately loud voice in team structure. When project managers dominate the discussions and own the narrative for the services. When the org chart is designed around reporting lines and budget centres rather than around software that needs to work together. When the people deciding team boundaries have never debugged a production incident or traced a request across service boundaries.

Domain isolation only works when domains are sized correctly. Too large and you’re back to the tragedy of the commons within the domain. Too small and you’ve created a distributed tragedy of the commons where the shared resource is human coordination rather than technical infrastructure. The sweet spot is teams large enough to own meaningful outcomes and small enough to maintain genuine accountability.

The Commons Solved

The shared infrastructure isn’t completely gone. Some things genuinely benefit from centralisation. But it’s the exception rather than the rule. And crucially, the teams that use shared infrastructure do so by choice, understanding the trade offs, rather than by mandate.

The tragedy of the commons is solved not by better governance of the commons, but by eliminating the commons. Give teams genuine ownership. Let them succeed or fail on their own merits. Trust that the Darwinian pressure will drive improvement faster than any amount of central planning ever could.

Nature figured this out a long time ago. It’s time enterprise architecture caught up.