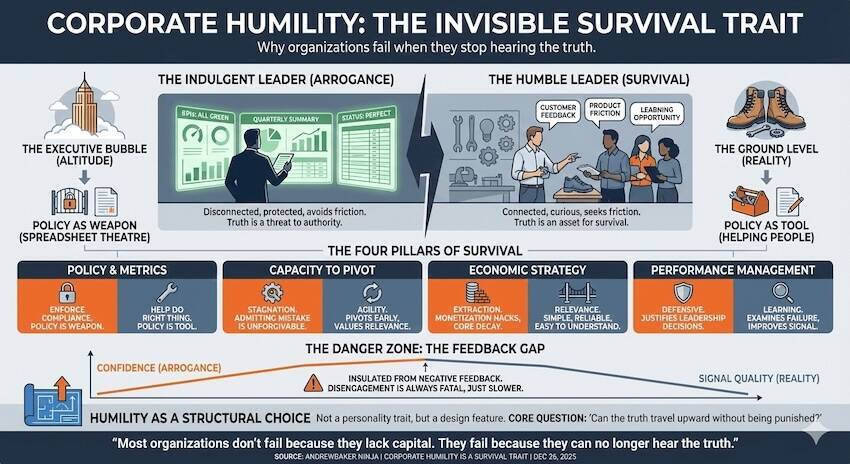

Most organisations don’t fail because they lack intelligence, capital, or ambition. They fail because leadership becomes arrogant, distant, and insulated from reality.

What Is Humility?

Humility is the quality of having a modest view of one’s own importance. It is an accurate assessment of one’s strengths and limitations, combined with an openness to learning and an awareness that others may know more. In organisational terms, humility manifests as the capacity to hear uncomfortable truths, acknowledge mistakes, and value input from every level of the business.

Humility is one of the hardest things to teach a person. It is not a skill that can be acquired through training programmes or leadership workshops. It is an awareness instilled during childhood, shaped by parents, teachers, and early experiences that teach a person they are not the centre of the universe. By the time someone reaches adulthood, this awareness is either present or it isn’t. You cannot send a forty-year-old executive on a course and expect them to emerge humble. The neural pathways, the reflexive responses, the fundamental orientation towards self and others, these are set early and run deep.

For companies, the challenge is even greater. Organisations are not people, but they develop personalities, and those personalities crystallise quickly. If humility was not baked into the culture from day one, if the founders did not model it, if the early hires did not embody it, then the organisation will struggle to acquire it later. Only new leadership and a significant passage of time can shift an entrenched culture of arrogance. Even then, the change is slow, painful, and far from guaranteed.

Two Models of Leadership

The Authoritarian, Indulgent Leader

These leaders rule from altitude. They sit on different floors, park in different car parks, eat in different canteens, and live inside executive bubbles carefully engineered to shield them from friction. Authority flows downwards through decrees. A skewed form of reality flows upwards through sanitised PowerPoint.

They almost never use their own products or services. They don’t visit the call centre. They don’t stand on the shop floor. They don’t watch a customer struggle with a process they personally approved. They never ask their staff how they can help. Instead, they consume dashboards and reports to try to understand the business that is waiting for their leadership to arrive.

Every SLA is green. Every KPI reassures. Every steering committee confirms alignment. And yet customer satisfaction collapses, staff disengage, and competitors with fewer people and less capital start eating their lunch. This is the great corporate lie: nothing is wrong, but everything is broken.

No one challenges decisions. Governance multiplies. Risk frameworks expand until taking the initiative becomes a career-limiting move. Over time, the organisation stops thinking and starts obeying. Innovation is outsourced. All new thinking comes from consultants who interview staff, extract their ideas, repackage them as proprietary insight, and sell them back at eye-watering rates. Leadership applauds the output, comforted by the illusion that wisdom can be bought rather than lived.

This is indulgent leadership: protected, performative, and terminally disconnected.

The Humble Leader

Humble leaders operate at ground level. The CEO gets their own coffee. Leaders walk to teams instead of summoning them. They sit in on support calls. They use the product as a normal customer would. They experience friction directly, not through a quarterly summary.

In these organisations, leaders teach instead of posture. Knowledge is shared, not hoarded. Being corrected is not career suicide. Authority comes from competence, not title.

Humble leaders are not insecure. They are curious. They ask why more than they declare because I said so. They understand that distance from the work always degrades judgement. This is not informality. It is operational proximity.

PowerPoint Is Not Reality

Authoritarian organisations confuse reporting with truth. They believe if something is on a slide, it must be accurate. They trust traffic lights more than conversations. They cannot understand why customer satisfaction keeps falling when every operational metric is green.

The answer is obvious to everyone except leadership: people are optimising for the dashboard, not the customer.

Humble organisations distrust abstraction. They validate metrics against lived experience. They know dashboards are lagging indicators and conversations are leading ones.

Policy: To Guide or Or a Weapon?

Humble organisations treat policy as a tool. Arrogant organisations treat it as a weapon.

In humble cultures, policies exist to help people do the right thing. When a policy produces a bad outcome, the policy is questioned. In arrogant cultures, metrics and policy are weaponised. Performance management becomes spreadsheet theatre. Context disappears. Judgement is replaced by compliance.

People stop solving problems and start protecting themselves. The organisation feels controlled, but it is actually fragile.

Arrogance Cannot Pivot

Arrogant organisations cannot pivot because pivoting requires one unforgivable act: admitting you were wrong.

Instead of adapting, they become spectators. They watch markets move, clients leave, and value drain away while insisting the strategy is sound. They blame macro conditions, customer behaviour, or temporary headwinds. Then they double down on the same decisions that caused the decline.

Humble organisations pivot early. They say this isn’t working. They adjust before the damage shows up in the financials. They value relevance over ego.

Relevance vs Extraction

Arrogant organisations optimise for extraction. They become feature factories, launching endless products and layers of complexity to squeeze more fees out of a shrinking, disengaging client base. Every useful feature is locked behind a premium tier. Every improvement requires a new contract or upgrade.

Meanwhile, the basics decay. Reliability, clarity, and ease of use are sacrificed for gimmicks and monetisation hacks. Clients don’t leave immediately. They disengage first. Disengagement is always fatal, just slower.

Humble organisations optimise for relevance. They are simple to understand. Predictable. Honest. They deliver value to the entire client base, not just the most profitable sliver. Improvements are included, not resold. They understand that trust compounds faster than margin extraction ever will.

Performance Management as a Mirror

In arrogant organisations, performance management exists to defend leadership decisions. Targets are set far from reality. Success is defined narrowly. Failure is punished, not examined. People learn quickly that survival matters more than truth.

In humble organisations, performance management is a learning system. Outcomes matter, but so does context. Leaders care about why something failed, not just that it failed. The goal is improvement, not theatre.

The Dunning-Kruger Organisation

Arrogant organisations inevitably fall into the Dunning-Kruger trap. They overestimate their understanding of customers, markets, and their own competence precisely because they have insulated themselves from feedback. Confidence rises as signal quality drops.

Humble organisations assume they know less than they think. They stay close to the work. They listen. They test assumptions. And as a result, they actually learn faster.

Humility Scales. Arrogance Collapses.

Humility is not a personality trait. It is a structural choice. It determines whether truth can travel upward, whether correction is possible, and whether leadership remains connected to the outcomes it creates.

Because humility cannot be taught, organisations must select for it. Hire humble people. Promote humble leaders. Remove those who cannot hear feedback. The alternative is to wait for reality to deliver the lesson, and by then, it is usually too late.

In the long run, the most dangerous sentence in any organisation is not we failed. It is: Everything is green. Because by the time arrogance has acknowledged reality, reality has moved on.